The number of photos of cats floating about the Intergoogles is testimony to how much we love photographing animals. But I bet we could all do it a bit better, whether they're our pets, cows on the closest farm, or gazelles in the wild. We've put together our top tips, dos and don't, and favourite recommendations for animal photography.

Pets and domesticated animals

Photographing pets is distinctly similar to photographing children: get down to their level, gird yourself with patience, and be ready to move fast. Much like my favourite photos of my nieces and nephews, many of my favourite photos of animals have been captured sitting (or crouching, in the case of mucky straw) on the floor, allowing them to play about me and simply being ready to capture kittens, lambs, hens, dogs, and various assorted being cute or idiosyncratic.

The chances are that you'll be exhausted and maybe a bit dirty at the end of it, but you should have some good photos. There is, of course, a bit more to it than that.

The non-negotiables

When it comes to taking photos of animals, some things should be on the checklist every time.

Get the eyes in focus - just like a portrait of a human, your viewers will be looking to make eye-contact with the subject, so get the eyes sharp.

Capture spirit - again, it's the same with humans, you need the photograph to convey the playfulness, the inquisitiveness, or the quirkiness of the animal.

The subject needs to be doing something - it doesn't matter if it's a dog asleep in a contrived position or a kitten chasing a toy, there needs to be something of interest happening in the shot.

Consider the background - you don't want clutter or a litter tray in the background of your photos, so pay attention to where you're taking them.

Be respectful - Don't do anything that hurts or distresses an animal for the sake of a photo. Don't pick up rabbits by their ears, provoke dogs, or yank horses' chiffneys or headcollars. Not only will the animal not like you for it, but it's unacceptable behaviour.

The debateables

Depending on the type of photo you're trying to take, you will need to make some choices. There's no right or wrong to these points; they're up for consideration.

Flash - Some people say avoid it altogether, others say use it judiciously. I'd say for heavens sake don't startle a sleeping dog or potentially damage a very young animal's eyes with flash, but used properly, you can produce some cracking shots with artificial light.

Kit - I've photographed animals with all sorts of camera and lens combinations. Sometimes, it's been a case of grabbing what's closest, so my iPhone, to ensure that I didn't miss the moment. Then again, I've headed down to the yard armed with all manner of lenses and a dSLR for photographing horses. Remember the adage that the best camera is the one you have with you, but don't forget to think about what you're trying to achieve with your photos, from portraits to macros to action shots, and select your kit appropriately.

The recommendations

Use a fast shutter speed - Unless you're trying panning, do aim to keep your shutter speed as fast as possible to avoid motion blur, particularly if you're aiming to capture animals at play. Up the ISO if you need to; noise is easier to fix than blur.

Consider your angles and proximity - while it's advisable to get down to the same level as your subjects, do consider shooting from above and below, too. The key here is to consider what you're doing and the story you're telling, rather than reverting to the default of standing up to shoot.

As well as the usual recommendation of getting closer, have you considered getting really close to your subject? Macro and abstract shots can work wonderfully to intrigue, inspire, and give a different perspective on your subject.

Grabbing their attention - I talk to dogs, use toys for cats, and make clip-clopping noises to encourage horses to prick their ears. If you know your pet, you'll know how to distract it or attract its attention. If the subject isn't your pet, talk to its owner.

Be careful

Cats scratch, dogs bite, and horses kick. They're also sentient and can be unpredictable. Don't do anything to upset your subjects or that endangers you. It's common sense, really.

Wildlife

While photographing pets is similar to photographing children, you might notice some similarities between wildlife and sports photography. You're going to be out in the elements, watching for the perfect moment, and most likely with a big lens. However, wildlife photography isn't restricted to the African savannah. There are squirrels in the park, birds in the woods, spiders in their webs, and wild monkeys in the Thai temple complexes. You don't have to travel to exotic locations to take wonderful wildlife photos. And if you are fortunate enough to be going on safari, you can always get in some practice with deer at home.

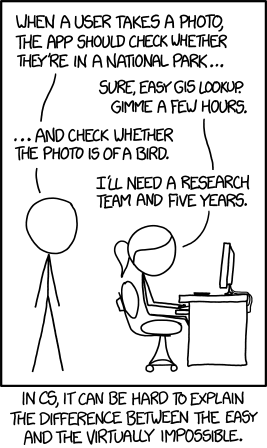

Know your subject - If you want to make the most out of your subject, then you need to know what to expect from it. Where are you likely to find it? When is it active? When does it feed? What should and shouldn't you do around it? There's little point arriving in the Serengeti in June and expecting to see wildebeest, as by then they'll be on their way to the Masai Mara.

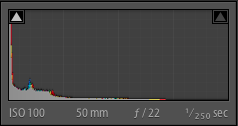

Know your kit - In order to be able to capture the wildlife images of your wildest dreams, you need to be intimately acquainted with your kit and understand its precise capabilities. How many extra stops does your image stabilisation really give you? What's the slowest speed at which you can hand-hold your camera? How high can you push your ISO before noise really becomes a problem? What's the optimal aperture for sharpness with your lenses? Do any of them have a proclivity to flare?

The better that you know your kit, the less time you'll have to spend fiddling and faffing and the more likely you are to make a crucial moment.

Use support - You might not necessarily want to use a tripod: it could be too cumbersome and too slow to move, but the chances are you'll need some kind of support for your camera when out in the field, particularly if you're using a long lens. Think about all of the options, from monopods to beanbags, and decide which one will work best for you.

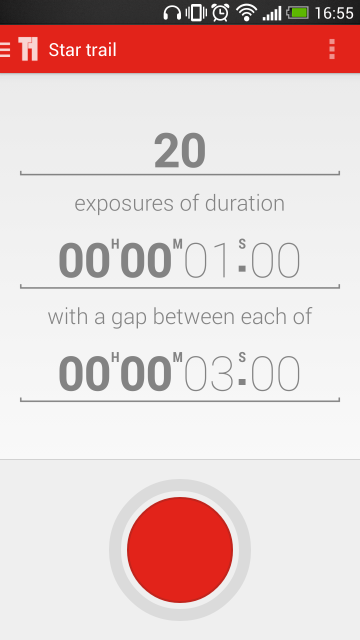

Be prepared - This isn't just about ensuring that you have the right camera kit with you and to hand, but also the right personal kit. In addition to cameras, lenses, filters, supports, remote triggers, batteries, and memory cards, you need to be dressed appropriately for the conditions and with changes of clothes if necessary. If you're as much as a feast for mosquitoes as I am, you'll need suitable insect repellant. You need to consider food and drink and appropriate storage for it. Do you require permits or a guide? And don't forget your sunscreen.

Capture action - The same as with pets and domesticated animals, aim to photograph action. Or at least if an animal is doing nothing, it needs to be doing nothing in an interesting way, for example with a glorious sunrise behind it, or curled up asleep in an unlikely pose.

Wide and close - You might well be using a long lens to photograph wildlife just to get close enough to identify it, but don't restrict yourself to close-ups. Think about placing your subject in its environment and providing it with context. Primarily, this is important for story-telling, but if you have travelled a long way to experience something magical, you'll want to record that, too.

Conversely, abstract close-ups can make for very striking photos. Don't be afraid to experiment!

Consider the light - While it probably should go without saying to think carefully about the quality, quantity, and direction of light, it's worth repeating. You might well find that as well as providing the best light for photography, the golden hours are also when many animals are at their most active.

Be careful and enjoy - Just as with pet and domesticated animal photography, be careful and be respectful. Don't do anything to endanger yourself or your subjects. Remember to adhere to the required codes and to clean up after yourself.

Finally, remember to enjoy it. Absorb the atmosphere and don't be afraid to put down your camera, either. Sometimes the picture in your memory can be better than the one taken by your camera.

More unusual ways of looking at things, remembering rules, and then breaking those rules, are in my lovely book, The Rules of Photography and When to Break Them. It's available as an e-book and in a dead tree version (UK, US).

More unusual ways of looking at things, remembering rules, and then breaking those rules, are in my lovely book, The Rules of Photography and When to Break Them. It's available as an e-book and in a dead tree version (UK, US).