Historically, split toning was used when developing photos from negatives. Two different toners would be used one after the other in order to produce different colours in the highlights and shadows of an image. For example, follow selenium with gold and you'll produce purple-blue mid-tones; or use sepia and then blue for sepia highlights, blue shadows, and green mid-tones. The effect could be altered by using different papers, too. While chemical split toning isn't an exact science, it does offer some compelling effects for your photos and can give them an entirely different feel. You can use it to add warmth or to cool down an image; you might want to introduce a blue tint, or an orange cast.

Now, split toning is more likely to be achieved using the dedicated split toning panel in Lightroom, or with a colour balance adjustment layer in Photoshop, and it is far more controllable. If you've not ventured into the split toning panel, the degree of variation that it offers you might be a little overwhelming; it can radically alter your photo in a ways that you might not anticipate. That shouldn't stop you from experimenting, and to get you started, here are some suggestions. And don't forget that if you're working in Lightroom, nothing can't be undone.

A quick introduction

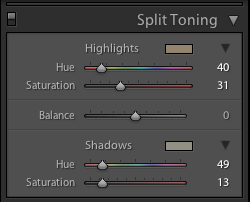

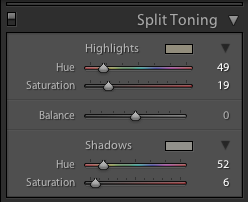

If you're using Lightroom, the split toning panel allows you to select the colours that you would like to emphasise in both the highlights and the shadows, the saturation for each of these tones, and then the balance between them.

If you find using the sliders to control these adjustments a little too abstract, click on the colour swatches beside 'Highlight' and 'Shadow' and use the eyedropper to select the precise colour you'd like for each.

The balance slider places more emphasis on either the highlights or shadows. Once you've selected your highlight and shadow tones, move it about a bit to see which direction, if any, you prefer.

Black and white

The original black and white conversion of Willie's portrait is coming up quite grey-green in tone. By adding some muted browns—that in the shadow very pale—you can introduce a great deal more warmth to the image and bring about an almost-sepia tone.

Adding warmth

This photo was taken fairly early in the morning, on a day when the cloud didn't lift. While the light was wonderfully diffuse, it wasn't especially warm. Even after correcting the white balance, it still felt as if it needed to be brought to life. By adjusting the highlights and shadow tones, it meant I could introduce a more golden-hour feel to the photo.

You don't need to push too far into the oranges or yellows to intensify the warmth in a photo: sticking to browns and beiges might be enough.

Of course, if you wanted to do the opposite and bring about a colder feel to a photo, you would do that by applying more silvery-blue tones, greys, greens, and even some yellows, to the shadows and highlights.

Cross-processed look

Until now, I've used fairly similar highlight and shadow tones in my split toning adjustments. But for a cross-processed effect, you need to select contrasting colours for your highlight and shadow tones: green and magenta, or cyan and yellow, for example. Which you apply will depend on whether you're looking for a warmer or cooler over all effect.

[gallery columns="2" ids="7128,7127"]

By adding a graduated filter, upping the contrast and saturation, and reducing the clarity, you can create a fake toy camera look. We've a tutorial for that, in case you'd like to give it a go.

Split tone away!

The best way to get a feel for split toning is to try it for yourself and see what you can achieve using it. Remember: if you don't like it, you can undo it.