From origins to the present day; from science to art.

Are photographs for humans?

Last month I was invited along to the inaugural EyeEm Festival & Awards. Among other things, I was on a panel on "The Camera of Tomorrow". I do quite a bit of panel-ing (is that a word?) but I'm unable to shake this particular one from my mind, because at some point, the discussion wandered into a topic that I haven't given much thought so far: Who actually consumes photography?

Are photos for humans or machines?

One of the big and scary ideas that came up was that the average photograph - or frames in a video, as may be the case - are no longer primarily for human consumption. As computers and image recognition becomes better, we now live in a world where even though if your photo is seen by 50 of your friends on Facebook, that very same photo will be seen by hundreds, if not thousands, of robots. Image recognition bots, facial recognition bots, localisation calculation bots, Google Images, scientific and statistical analysis bots... Who knows.

If you think about it: say you are a scientist who is trying to map the increase or decrease of water in a particular lake. You could install expensive equipment - but where would you get historical data? Well, if that lake happens to be a popular holiday destination that people tend to share photos of, you could actually do image-driven research: Photos taken on smartphones are tagged in the metadata by time and GPS location; Scrape the internet for photos taken in that particular location, then use image recognition software to estimate the water level in the lake. Science fiction? Nope - perfectly possible, and projects like this are already in action at universities and in commercial settings all around the world.

That's a relatively benign example: What about the data we put out there ourselves? That the trend of taking selfies is an incredibly powerful tool: By posting photos to Twitter, and describing (or even hashtagging) the photo as a 'selfie', it means that over the years, computers can start to map your ageing process, and potentially learn about the way that human faces tend to age. Add a layer of geo-location on top, and perhaps scientists will find that humans living near power stations have, on average, slower hair growth (just to pick an example). To a data scientist / statistician, the possibilities are absolutely mind-boggling.

Of course, there are less salient uses too: By posting selfies online, you're feeding an incredibly powerful facial recognition opportunity: Facial recognition based on a single photograph can be incredibly difficult (think about it: You're just a new pair of glasses, a baseball cap, or a beard away from looking very different from a single photograph). If, instead, one were to collect all the photos I've ever posted of myself online, you've got a huge amount of data: What I look like in different lighting situations, with a hat, with a beard, with glasses on, in the morning, in the evening, smiling, angry, moody... All of this is data that could be used to create a mathematical formula for what "I" look like. Feed that into a network of CCTV cameras (they say that you can travel from anywhere to anywhere else in London without ever stepping out of reach of a CCTV camera), and it's possible to track my every movement through my home city. Scary? Perhaps - but against that lens, it becomes all the much clearer that the chief consumer of imagery is, indeed, computers - and by sharing photos of ourselves, we're making it all a lot easier for whoever wants to track us around.

Is there anything machines can't do better than humans?

Ok, so we're being ruled by robotic overlords; what else is new... Is there anything humans can actually do better?

Of course, you can teach a computer to take photographs - it isn't even a very big challenge. A computer could even take some highly proficient photographs, technically: Focus, white balance, depth of field, colour saturation - even triggering the camera at exactly the right point in the process of taking a photo is all describable mathematically, which means that computers are rather good at it. In fact, when you think about it: Most of us heavily rely on computers already: Exposure light meters, automatic focus - they've been the computer-powered helpers in the world of photography for years, and we wouldn't want it any other way.

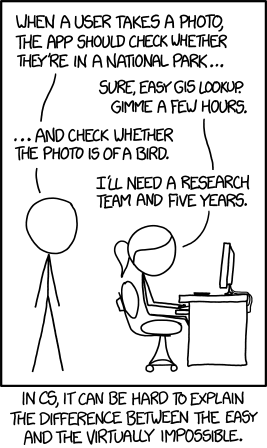

The other side of photography, however is trickier: The artistic side. This is where a recent XKCD comic hit the nail on the head:

Put simply, whereas a photo can be objectively 'bad' technically (Out of focus, motion blurring, white balance issues, exposure issues, wonky horizons, etc etc etc), deciding what makes a good photograph creatively can be very difficult to ascertain even to humans (Go on, give it a shot: See if you like / admire / understand why each of the top 10 photographs picked by Time magazine to be the best of 2013 were chosen. There is a recurring theme; more about that below).

Of course, what makes a 'good' photo is partially down to taste and cultural convention, but also down to a very difficult to answer question in general: What makes a good photograph? There are a few technologies that already exist to help people determine which photo in a burst of shots is 'best' tends to be limited to technical elements (From a set of 10 photos, pick the photo with the least camera blur, the least motion blur, and where people aren't blinking), rather than the aesthetic side of things.

But what about the story?

The other - and perhaps most important part - of photography is where machines truly fall short: Computers may one day be able to create photographs that are technically proficient and aesthetically pleasing, but the most powerful photographs are the ones that have a third layer: A story that's worth telling; a story worth listening to, and thinking about.

Every photograph that ever tugged at your heart-strings will have done so because it tells (part of) a story. In fact, the photo doesn't even have to be particularly creative or technically perfect - a slightly blurry photograph of your recently deceased grandmother could move you to tears - not because of the photograph, but because of the story it tells.

Ultimately, the story is all that matters; A technically perfect photo of a person is a photographic rarity, and may be interesting for that reason. If the lighting and setting is also great, you may be on to a good artistic photograph too. But the reason we identify with portraits is the stories they tell: Either because we (think we) know the person in the photo, or because we, as human beings, relate to something about the person in the photograph.

It may very well be the case that machines have overtaken humans as consumers of photography, but machines have a different purpose than humans: Computers see photographs as datapoints in an almost unfathomably large matrix of data. Humans see photographs as stories and memories. Maybe that's a thought worth taking with you into your next photo shoot - I certainly will.

Pass me a C-47 - or how a clothes peg got its film-set name

I was flipping through a book on film-making when I stumbled over a box-out mentioning the C-47. Or a clothes peg. Wooden clothes pegs are much-used on film-sets, where they don't conduct heat so can't burn people or melt. They make perfect handles for hot barn doors and they hold gels in place without dribbling into a puddle on the floor. Not to mention their grip over scripts, straws, and cables. Sometimes simple soilutions are the best. It did set my mind a-thinking, however. How did the humble clothes peg come to be known as a C-47? After a little digging, I don't have a defnitive answer, but I do have some pleasing stories.

After a plane?

The C-47 was a plane used extensively throughout the Second World War for troop movements, medical evacuations, and reconnaissance, and afterwards when it played a crucial role in the Berlin Airlift. It was a versatile plane, which mirrored the versatility of the clothes peg. Servicemen returning from the front to film studios carried over the name.

From a storage bin?

Some film studio somewhere stored its clothes pegs in a bin designated C-47. The name has stuck.

Its requisition number

Clothes pegs were assigned the catalogue or military requisition number C-47. They became known by their catalogue number rather than their common-or-garden name. Which leads neatly into the accountancy theory...

For accounting purposes

When gaffers and key grips were submitting requisition forms or expenses claims to film studio executives, accountants, and tax officials, they had trouble doing so for a bundle of clothes pegs, no matter how vital their presence was on set. By changing the name to something far more significant sounding, for example the clothes pegs' catalogue number, nit-picking officials were none-the-wiser and the best boys', grips', and lighting crew's fingers remained unburned.

Finally...

It makes a great joke to ask the new boy or girl for a C-47 and they have absolutely no idea what one is. And I'm reliably informed that what I know as a clothes peg (or even just 'peg') here in the UK is known as a clothespin in the US. Not that I'll be using any today for their traditional purpose of hanging washing on a line: it's pouring down.

Written with help from:

- Know your film jargon: The (questionable) true story of the C-47, from Scouting New York

- Pass the C-47s, from DeHavilland's Livejournal

- C-47 Skytrain Military Transport, from Boeing

Gursky's Rhine II - small potatoes in an auction house

How sharp was your intake of breath when you read the Andreas Gurksy’s Rhine II sold for US $4.3 million (£2.7 million) at auction at Christie’s, New York last week? For most of us $4 million is an obscene amount of money to spend on anything, let alone a photographic print. But baby, this is small potatoes in an auction house. For some people this sort of money is pocket change. When I was 18, I was an intern at a London art dealers. The painting hanging on my office wall was a Renoir worth £6 million. So it got me thinking, how does Gursky’s print compare against a few other things sold at auction?

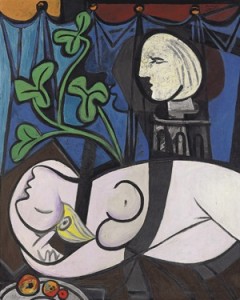

Let’s start with the most expensive painting sold at auction. That would be Picasso’s 1932 Nude, Green Leaves and Bust. Like Gursky’s photograph, it was also sold by Christie’s in New York, but in May 2010. The sum it went for was a little more than Gursky’s print, though. An anonymous buyer handed over US $106.5 million for it. Heaven only knows what that dude’s insurance premium would be.

That Picasso isn’t the most expensive painting ever sold, though. That honour goes to a Jackson Pollock, called Number 5, 1948, which David Geffen sold privately to an anonymous buyer in 2006. The precise sum wasn’t disclosed, but it’s widely believed to have been a shudder-inducing US $140 million.

What about a sculpture? Alberto Giacometti’s 1961 L’Homme qui marche I sold at Sotheby’s in London for US $104.3 million in February 2010. At the time, that made it the most expensive piece of art ever sold at auction.

Laurence Graff left school at 14 and began his career cleaning toilets. He’s now the owner of a diamond mine in South Africa as well as the Graff Pink – a potentially flawless 24.78 carat pink diamond – that he bought for £28.8 million at a Swiss auction house in November 2010. The boy made good.

The same thing couldn’t really be said for the most expensive racehorse sold at auction. The Green Monkey was bought by John Magnier for US 16 million in 2006. He barely saw a racecourse and was retired a maiden. Mr Magnier is well aware that you win some and you lose some, though. That’s just racing.

So in the grand scheme of things, US $4.3 million isn’t that much for a photograph, even if The Guardian did describe it as a sludgy image of desolate, featureless landscape. Ladies and Gentlemen of the photographic profession, we’d better get cracking with our sales.