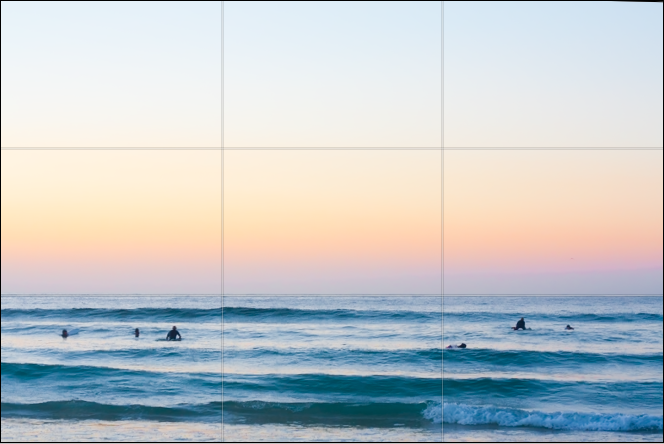

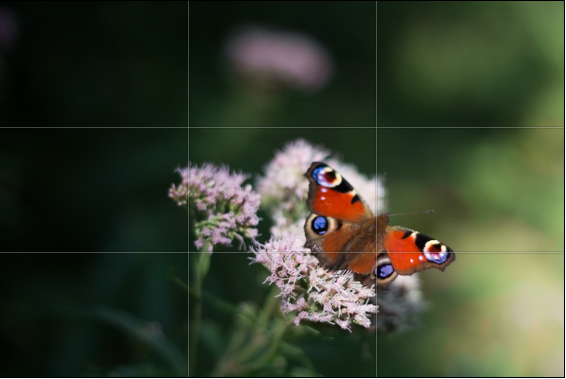

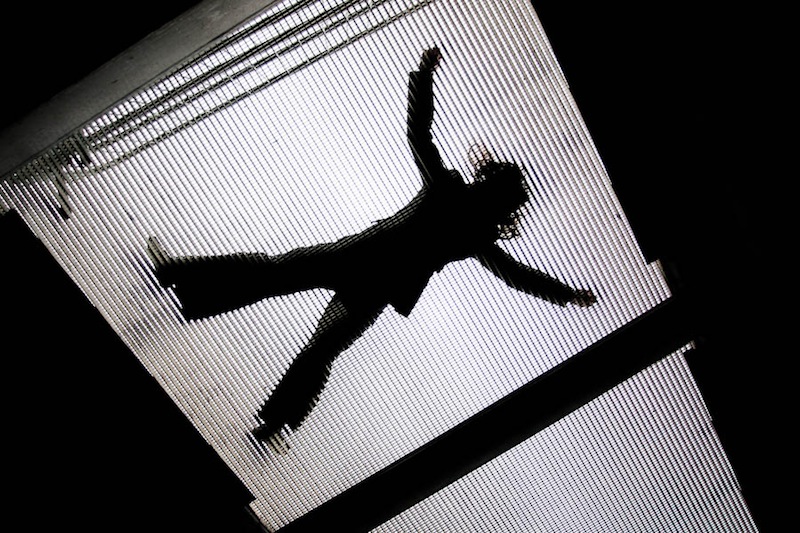

We put pictures—whether they're paintings or photos—into frames to help direct the viewer's eye. The frame is a boundary that directs the gaze: it ensures we know precisely where to look. As well as creating a border from a mounted frame and from the edges of a photo itself, it's also possible to bring focus to your subject and compositional strength and depth by using natural frames within your photos. Despite the name, a 'natural frame' doesn't have to be organic in origin, although trees, streams, and cave mouths do indeed create beautiful natural frames, rather the term describes a frame-within-the-frame. Look out for windows, doorways, and arches—in fact anything that bounces the eye back towards the subject—to act as a frame.

Why the eye likes natural frames

Primarily we appreciate images that include natural frames because they direct the eye straight to the photo's subject. As the eye travels towards the edges of the image—and especially if it contains lines that drag the gaze away from the subject—a frame helps to draw it back toward the focal point, just where you want it.

Second, they can bring a sense of perspective and three-dimensionality to an image, giving you the sense that you're looking through one layer of an image and on to another.

A frame can also give a sense of place or give context to your photos, for example, indoors versus outdoors or a modern area versus a historical one.

Finally, we find images that make use of natural frames attractive because it brings a sense of order to the image, in much the same way that triangles bring order to scenes with multiple subjects. They place limits on the scene and provide it with some boundaries.

Composing with natural frames

Just because your scene has a terrific natural frame within it, it doesn't mean to say that you can ignore any other compositional theory. You still need to consider your use of lines, your subject placement, and the balance of the shot. Remember: combining these compositional techniques can help to elevate a good photo to a great one.

Frames and depth-of-field

If you're planning on using a natural frame in your composition, consider if you want the frame itself to be sharp or blurred. If your subject and frame are at different distances, but you wish them both to be in focus, you'll need to use a relatively small aperture to achieve an adequate depth-of-field. Of course, having the frame in focus might prove a distraction and defeat its purpose, in which case using a larger aperture and isolating the subject using a shallow depth-of-field will work better.

Metering

If you're inside a cave or tunnel and using its natural form to provide a frame for a brightly lit sbject on its outside, you will have to meter accordingly. Spot-metering for the well-lit subject might be the easiest option. Alternatively you could dial in some negative exposure compensation should you prefer to stick with matrix (or evaluative) metering.

In order to capture the full dynamic range of such a scene, with its bright exterior and dark interior, you would need to shoot two differently metered images and combine them using post-processing software.

Don't over do it

Using frames-within-a-frame is such an effective compositional tool that it's all too easy to get carried away with them and over-use them. One natural frame within a portfolio is clever; a dozen is cliché. Just because a potential natural frame exists doesn't mean it is the best way to compose the shot; it needs to bear some relationship to the main subject.

If you're not sure if a natural frame is appropriate for your photo, ask yourself: Does the frame add drama to the photo? Does it help to tell a story, add context, or give a sense of depth? Does the frame help to illustrate or enhance the focal point of the photo? If the answer is no to any of these, you might be better looking for an alternative composition.