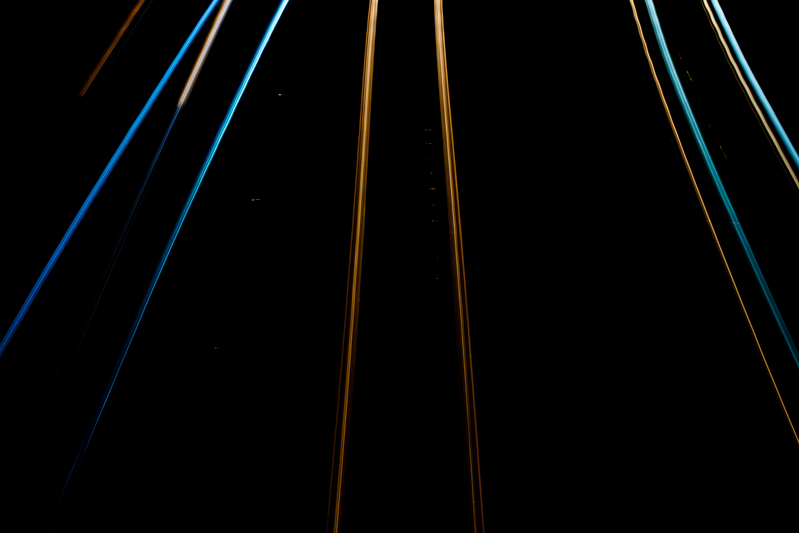

If you'd like to try a more unusual approach to lighting a photo, whether that's because you want to experiment or because you don't have access to studio lights, you might want to consider light painting. This isn't the type of light painting when you make patterns and shapes and designs with light sources to create your image, but using light sources to illuminate your scene during a long exposure. At its simplest, it involves outing the lights, setting your camera to bulb mode, and using a torch to 'paint' light onto your subject. Want to give it a go? Read on!

Kit

You don't need anything especially fancy for light painting: a camera on a tripod, a scene that you want to illuminate, and a torch are the minimum requirements. You might find it easier to control your camera's shutter using a cable release for flexibility and when you're more confident you might want to try some more advanced techniques, but let's start here.

Imagining your scene

Before embarking on your light painting adventure, it's best to think about the scene that you want to illuminate and the story that you want to tell. While you might herald some impressive results from waving your torch about in random formations, that's unlkely to result in the image that you anticipated. Take a little time to consider your subject and how you want to light it.

Camera!

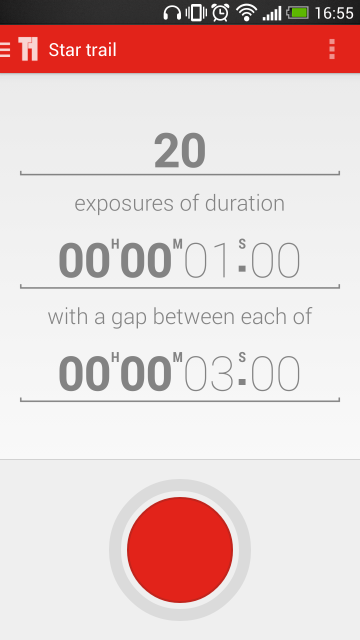

Scene set and lighting scenarios imagined, you need to secure your camera on your tripod and select your exposure. For light painting, try bulb mode controlled by a cable release, a low ISO, and an aperture that gives you the look you want. You'll need to manually focus on your subject, too!

Lights!

Turn out the lights and start your long exposure.

Action!

Use your torch to begin to paint light over your subject. There's going to be some trial and error involved in getting the effect that you want, but that's half of the fun! Not keen on what you see? Try it again!

Stretching your creativity

When you've mastered the basics, you can push your experimentations further. Try introducing coloured light to your images by covering your torch with coloured gels, or even sweetie wrappers. You can make cut-out filters to shape your light. Or direct your light more accurately with a snoot manufactured from cardboard and gaffer tape. You're not limited to inside, either. Try light painting buildings and monuments or flower pots - whatever takes your fancy and you've sufficient fire-power to illuminate!

This is something that doesn't have to cost the earth but can render some fabulous results.

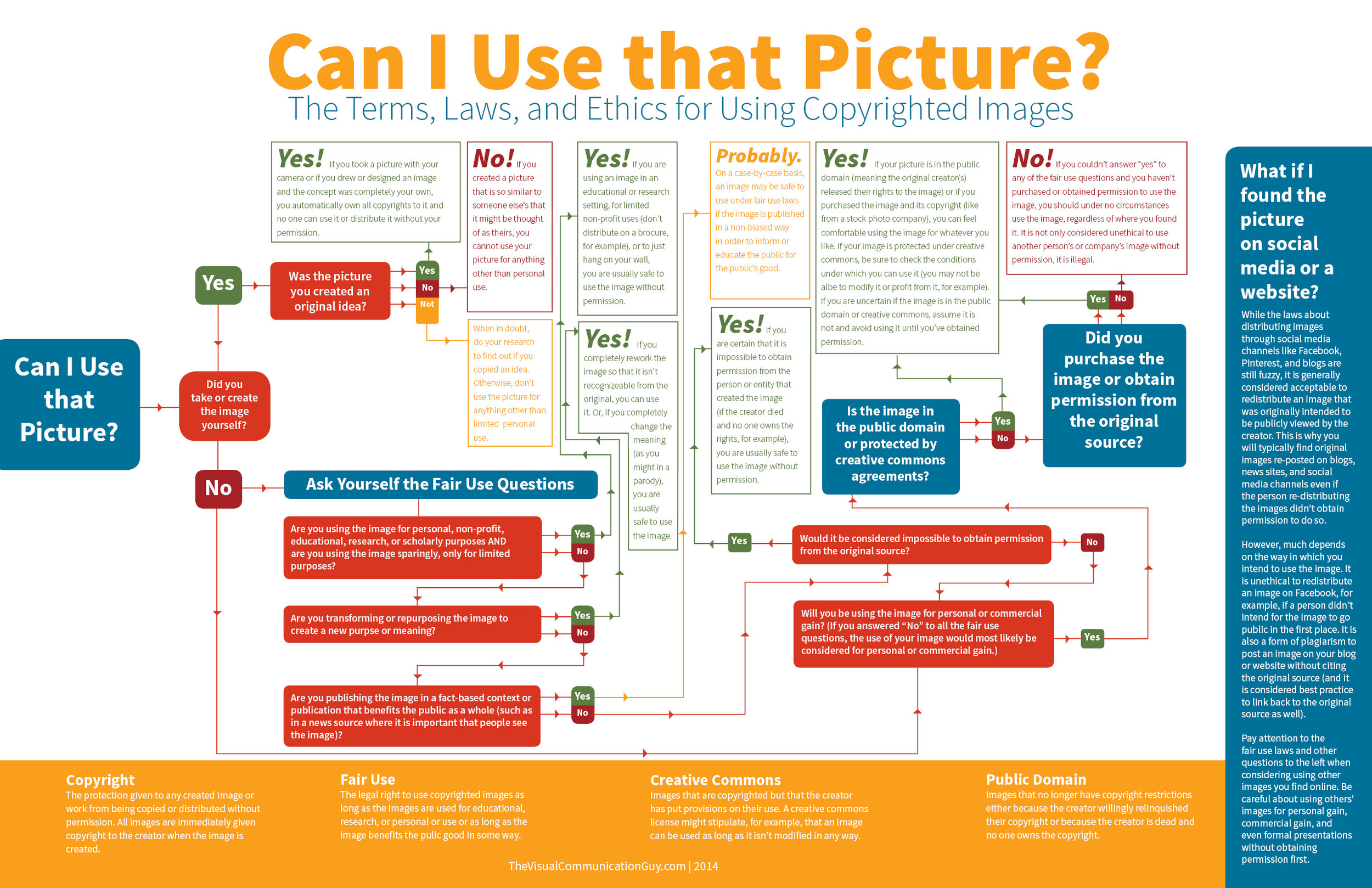

Much of this, including all the images, is based on the fantastic How to paint a still life with light tutorial found on Triggertrap's How-To microsite, and it's reproduced with permission. Triggertrap How-To is full of great content for making the most of your camera. You should take a look.