How you display your images can make or break them. But who among us really knows the finer points of how to do it? This infographic should help!

Composition in a nutshell

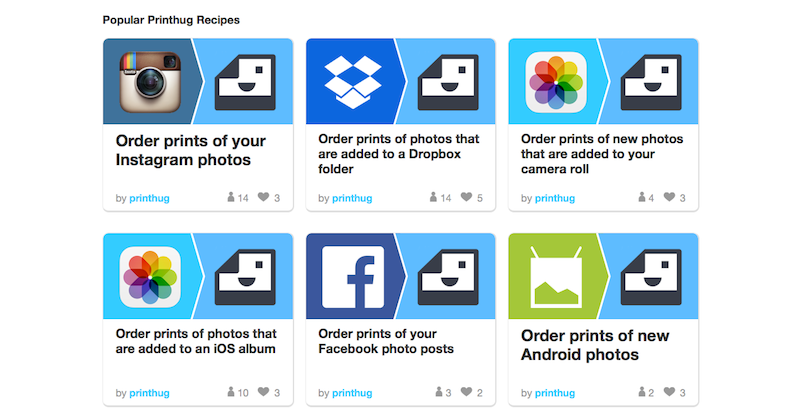

From screen to print with Printhug and IFTTT

Tell the truth, how often do you print any of your photos? And how often do you go to have a selection of your images printed only to be deterred by the prospect of having to upload them to a print company's website, which always seems to be a slow process, and then prevaricate about their sizes and formats? If the answer to the first question is 'not very often' and if the answer to the second question is 'more often than I'd like', then photo print service Printhug has an IFTTT-based solution to transfer images from digital to print with the minimum of fuss.

Should you have not heard of IFTTT, it's an automation programme that allows you to write 'recipes' to connect various apps and services in your digital life (IFTTT calls them 'channels') in order to do things. All recipes are based on the statement 'If this, then that.' If you do something on one channel, this prompts an action in another channel. If I publish a new article here on Photocritic, a tweet is posted on Twitter linking to it.

With Printhug, you extrapolate the IFTTT theory to 'If I post an image to Instagram and tag it #printhug, then Printhug will print it.' You can substitute 'Instagram' for 'Facebook' if you prefer. Or have the images that you upload to a particular Dropbox folder sent to print without any fuss.

Print orders can be aggregated from several different sources, for example Instagram, Flickr, and Facebook, and a minimum order can be set, too, ensuring that you accumulate a viable number of prints before they're mailed to you.

Square photos are automatically printed in 4×4" format (49¢ each), while you've a choice of 6×4" (49¢), 7×5" (89¢), and 10×8" ($3.49) rectangular prints.

Printhug ships to USA, Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Mexico, New Zealand, Spain, and the United Kingdom. How much it'll cost will depend on how much you order.

Want to give it a go? Head over to the Printhug website to learn more and sign up. Or take a look at the Printhug channel on IFTTT.

Standing out in the crowd - or how to take meaningful photos among lots of people

'Tis the summer (here in the northern hemisphere). 'Tis the season for festivals and fairs and fetes. 'Tis the season when people might want to capture crowd scenes with their cameras. Shooting crowd scenes is easy, yes? There's so much going on that all you have to do is raise your camera, point it in the right direction, and shoot to produce an interesting photo, yes? Ehm... no. Anyone who's ever tried to take a compelling crowd scene photo will appreciate that it's far harder to get it right than it is to get it wrong. Frequently, crowd photos emerge as amorphous collections of strangers with no clear narrative or obvious focal point. Anyone whose attention doesn't wander irretrievably will be left asking 'So it's a photo of what?' But mostly the eye will scan over an ordinary crowd scene shot, fail to find anything of interest and be drawn into the story, and move on to the next shiny thing. Your audience is gone.

What makes crowd photos so difficult? The very fact that there is so much going on in these scenes is usually their undoing. Every photo must tell a story. (Along with 'Get closer!' and 'Just because it's on the Intergoogles, it doesn't mean it's free to use!' it forms the third edge of the Photocritic mantra triumvirate.) Rather than expecting your audience to determine what the story might be among the tens, maybe even hundreds, of people, you have to set about deciding on what the story is and composing an image that conveys that.

When you're thrust amongst a crowd, or are perhaps looking down upon one, ask yourself: 'What am I trying to relate here? What's the story?'

Perhaps it's the sheer number of people? Maybe it's the focus of thousands of individuals on one figure on a stage? Is it a solitary red shirt in a sea of blue? Sometimes it's a case of waiting patiently for that moment: a sting of eye contact, a dropped doll, a wearied pause. Define the story and you're halfway to creating a compelling image.

Now, ask yourself: 'What can I do to convey this?' How you compose and expose your photo will ensure that your audience can grasp what you're trying to say and will help them to connect with it.

When you're trying to express numbers, find a point of juxtaposition to emphasise them: look for something small or noticeable that stands out and contrasts against the heaving mass. When a horde is focused on one thing, use lines to direct the viewers' eyes and channel them into the moment. For an aberration in the flow of things, try to isolate the rogue figure and plant it amongst the norm.

Rather than point and shoot, hoping that you'll produce an image that people will find interesting, draw on your compositional skills—the rule of thirds, leading lines, colour theory, pattern and repetition—together with your technical knowledge—focal length, aperture, shutter speed, and metering—to tell a story. Then you'll capture the crowd.

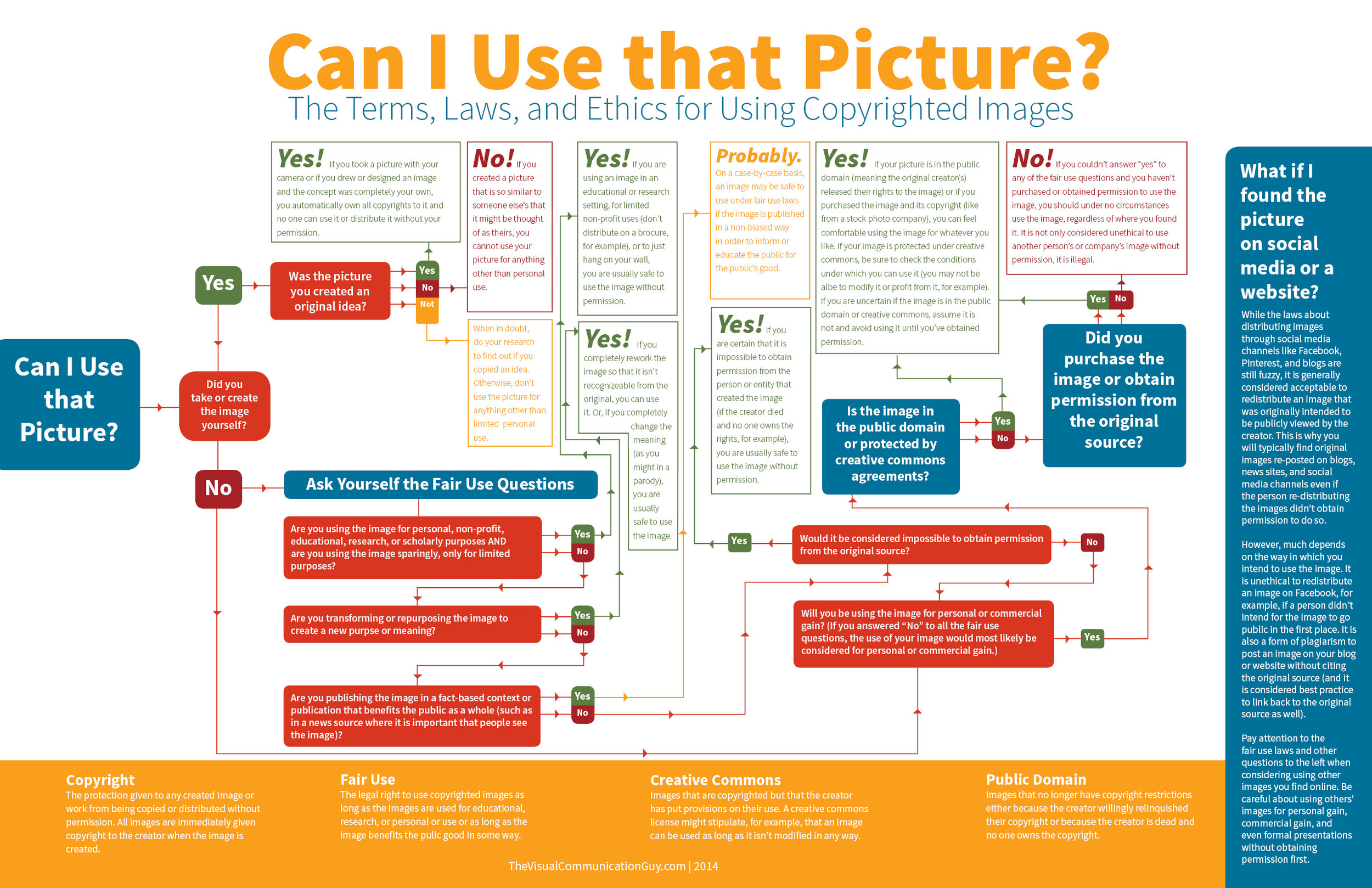

Just because you found it on the Intergoogles it doesn't mean it's free to use

I was having a fairly good morning, until I took my lunchtime peruse of Feedly to see if anything interesting or exciting had dropped into it. Apart from a new post by my favourite film critic, nothing was outstanding until I reached Lifehacker. The Lifehacker team has just posted a link to a visual media usage rights flowchart created by The Visual Communication Guy. Excellent! Ignorance is no excuse when it comes to image theft and unauthorised use and reproduction of photos. While we're all perfectly aware that when you place something on Facebook, Flickr, or your personal version of Frankie's Funky Photos, there's a real chance that someone will try to use it improperly, the more that we can educate people about the right way to do things, the better. This one, however, was not quite so excellent.

You'll find the original here and the Lifehacker article here.

Apart from the fact that it's far too dense and word-heavy, it contains at least one humongous, glaring, verging on the unforgiveable fault for something that purports to advise on usage rights. Take a look and tell me if you can see it. (And tell me how many others you can see. There are plenty.)

Found it?

If you haven't, because it's a horrid thing to read, here it is:

While the laws about distributing images through social media channels like Facebook, Pinterest, and blogs are still fuzzy, it is generally considered acceptable to redistribute an image that was intended to be viewed publicly by the creator. This is why you will typically find original images re-posted on blogs, news sites, and social media channels even if the person re-distributing the images didn't receive permission to do so.

No, no, no, no, no, no. And for good meaure I'll say it again. No.

Images that are shared on social media aren't free for redistribution unless the creator has expressly said so. I put my images on Flickr and use them here on Photocritic and put them on my personal website to display them, to illustrate concepts, to tell stories. I do not put them on the Intergoogles so that anyone else can make use of them. And you should never assume that anyone else does, either.

The law regarding this is hardly fuzzy about the situation, either. There's been at least one monumental court case that supports this opinion, when photographer Daniel Morel sued AFP and Getty Images after they redistributed his images from the Haitian earthquake, which he'd shared via Twitter, without his permission.

Copyright exists from the moment that someone creates something, whether it's a photograph, a tune, a poem, or a piece of prose. It doesn't matter how a creator wishes to share her or his creation with the world, unless she or he has definitely signed away the rights to it, the rights remain theirs.

To be fair to the Visual Communications Guy, he does state 'My rule above all else? Ask permission to use all images. If in doubt, don’t use the image!' in the post that accompanies the flowchart, but that's not really good enough. It's the flowchart that people are going to share and see, not the article. When incorrect information such as this gains traction, we all suffer. Suddenly what's not right becomes commonly accepted. Or people who were doing their best to not be ignorant are in the wrong when they thought they were doing right.

So I'll say the mantra and everyone can repeat it after me: 'Just because I found it on the Internet, it doesn't mean it's free to use.'

Is the new Pentax Q-S1 all fur coat and no knickers?

When the press release for Ricoh's newest camera fell into my inbox yesterday, I felt overcome by a sense of deja-vu as I scanned down it. The specification for the Pentax Q-S1, a pocket-sized EVIL camera, seemed very familiar: 12 megapixel 1/1.7" CMOS sensor; ISO 12,800, 5 frames-per-second; DR II dust removal mechanism; and Eye-Fi wireless LAN SD memory card compatibility. Isn't that the Pentax Q7 in all but name? Looks-wise the Q-S1 didn't appear exactly ground-breaking either. That might sound contradictory for a camera that comes with five different body colours (black, gunmetal, pure white, champagne gold, bright silver) and eight grip colours (charcoal black, cream, carmine red, canary yellow, khaki green, royal blue, burgundy, pale pink), but Pentax is famed for its swap-shop approach and the design is making the retro-but-not overtures that feel almost inescapable right now. It has very similar dimensions to and weighs almost the same as the Q7.

Try as I might, I couldn't pin-point any significant differences, save for the physical appearance, between the Q7 and the Q-S1. The Q-S1 is supposed to have a slightly improved auto-focusing system and has updated filters, but that's about it. Improved autofocus is always appreciated and quite frankly I can take or leave filters and toys, but I'm still scratching my head. What's the point of the Q-S1?

If Ricoh is of the opinion that the Q-S1 is there to offer consumers more aesthetic options and choices, that's a grimly disappointing approach to selling cameras. I admit that I have been known to go weak at the knees owing to the sumptuous design of a camera on occasion, but I part with my money because of their guts and performance. Cameras are tools, not fashion accessories and what truly interests me are technological developments that make a difference. Dressing up the Q7 with its tiny sensor that suffers from noise issues won't make it a better camera.

I'm desperately hoping that camera buyers aren't so superficial that everything rests of the look of the box that lets in light and not how well it allows the photographer to control and manipulate that light, or how well it records that light. I can't be sure but I blinking well hope that isn't the case.

So Ricoh and the Pentax people who work there, if you're listening, I'm sure that you can do better than this. There's the Pentax 645D on your roll, after all. And people who buy cameras: it's about making beautiful things, how your magical picture-making box looks isn't all that important. Not in the grand scheme of things.

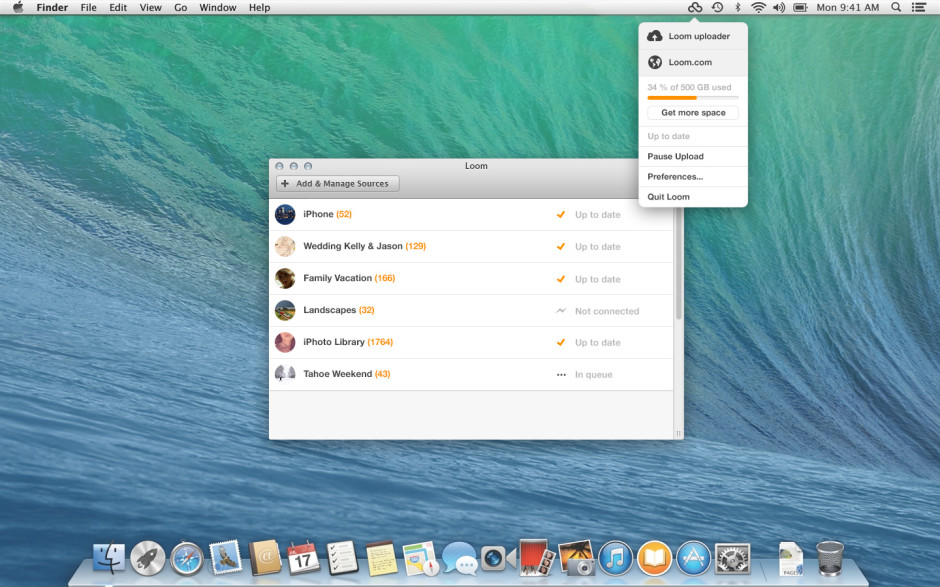

Loom weaves together your photos from multiple devices into one place

For a little while now I've been testing out the public beta version of Loom, an online photo library that is synchronised across my different devices. In all, I've been rather impressed by what I've seen and given it left public beta today and now anyone can sign up for a Loom account, it only seemed fair to share. With so many cloud storage options available, why would you want to sign up for Loom? From its developers' perspective: 'We’re making it quick and easy for you to access and manage your entire photo and video library on every device, without taking up local storage space.' The idea is that whatever device you used to take a photo and wherever it has been stored and developed initially, you can bring it into Loom's weave and have it accessible and identifiable wherever you are and whether you're on your iPhone or sitting at your Mac. Then you can share it, if you want, via email or message.

From a user's perspective, it does what the founders intended: makes it easy for you to look at all of your images in one place.

Install Loom on your iPhone and when you first log in you'll be asked if you want to transfer your entire camera roll to your Loom library. I clicked 'Yes'; it took a while, but it transfered the lot. Now, every time that I open Loom it copies my new images and videos over from my camera roll to Loom. By selecting the 'Nonstop upload' option in settings, it enables uploading even if you close the app. Useful when you need to shift large numbers of photos in one sitting.

If you install the Loom uploader on your Mac you can use it to hunt down the photos on your internal or external hard drive, be they JPEGs or Raw, and back them up to the cloud. The Loom team reckons that it can support over 130 different types of Raw file, but if you find one that won't trip the light fantastic, let them know and they'll try to fix it.

All of your images will appear in your timeline, but you also have the ability to file them according to whatever Byzantine or idiosyncratic method you prefer. If you delete a photo from your local drive or your phone, it'll still be there in Loom. This has allowed me to free up significant space on my iPhone, precisely what the Loom team intended. (Yes, the photos are backed up somewhere else, too!)

At present, Loom is iPhone-, iPad-, and Mac-only; however, there are plans to widen its access in due course. The team is very keen to hear what its users want from the service, too. As well as opening itself up to public subscriptions, which might generate it some income, it has also received $1.4 million in seed funding from sources that include Tencent, Google Ventures with MG Siegler, Great Oaks VC and angel investments including Will Smith (Overbrook Entertainment), and Damon Way (founder of DC Shoes).

Your first 5GB of storage comes free; after that there's a 50GB option that costs $39.99 for the year or you can pay $99.99 for a year of 250GB storage. You've nothing to lose by checking it out.

Love, Captured: a rather sweet photo competition from eHarmony

In celebration of its fifth birthday, online dating site eHarmony is running a rather sweet photo competition; it's looking for photos that capture the essence of love. They can be slushy, smoochy depicitions of couples in love or slightly more abstract interpretations of the giddy sensation. There's a £5,000 prize for the winner, which will be selected from 25 finalists by four judges: relationship expert Jenni Trent Hughes, editor of Practical Photography Ben Hawkin, photography blogger Annie Spratt (aka ‘Mammasaurus’), and Marketing Director of eHarmony.co.uk, Romain Bertrand. They'll be making their decision according to three criteria: creativity, quality, and charm.

Entries can be submitted between now and 17 January 2014. You must be over 18 and a UK resident to enter, you can submit as many images as you wish, but they cannot have been previously published. As always, I recommend that you read the terms and conditions carefully. All the details are to be found on the Love, Captured website.

Good luck!

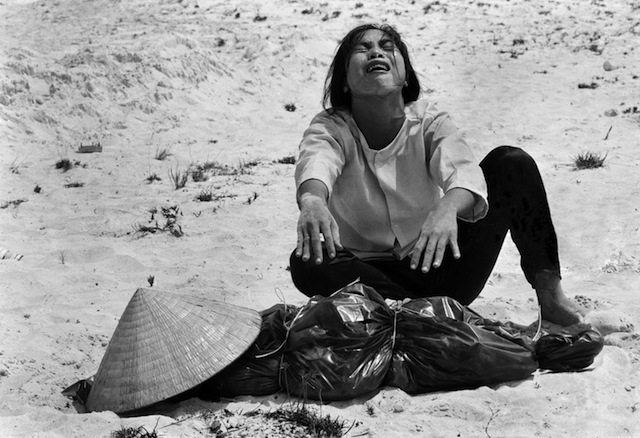

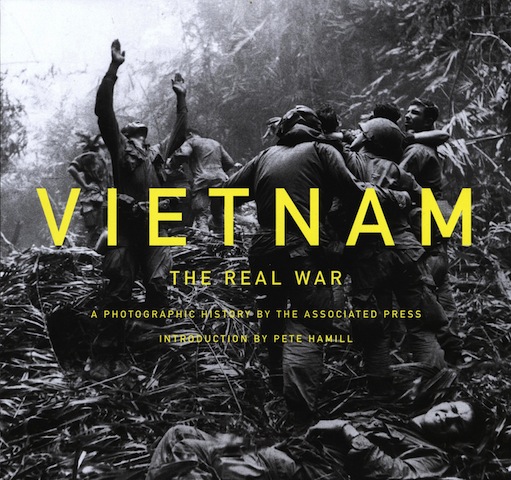

'Vietnam: The Real War' - a book of 300 seminal images from the Associated Press

The Vietnam War is sometimes referred to as the 'last newspaper war' - there were TV news reporters there, but their cameras weren't as discreet and portable as 35mm stills cameras and we didn't yet have rolling news coverage. The conflict's iconic images were seen in print, and iconic they were. Many of them are immediately recognisable even if you never saw them on the day that they were published. The Associated Press had over 50 photographers posted to Vietnam, four of whom won Pulitzer prizes for their coverage. Their images documented the war from positions of unequalled battlefront access and today, to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the conflict, 300 of their images are being published in a new book: Vietnam: The Real War.

Fifty years on, even after seeing them so many times, these images never fail to shock, horrify, or give you cause to reflect. The collection includes Malcolm Brown's photo of a Buddhist monk self-immolating on a Saigon street in 1963. It was this image, supposedly, that prompted President John F. Kennedy to say: 'We’ve got to do something about that regime.' And there's Nick Ut's photo of a scorched, naked girl fleeing a napalm attack, the veracity of which President Richard Nixon allegedly questioned. Showing the impact of the war on civilians, soldiers, and rebels, the book is a testimony to the power of conflict reporting.

The book's introduction is by Pete Hammill, who reported from Vietnam in 1965. 'Across the years of the war in Vietnam, the AP photographers saw more combat than any general,' he says. 'This book shows how good they were. As a young reporter, I had learned much from photographers about how to see, not merely look. From Vietnam, photographers taught the world how to see the war.'

Vietnam: The Real War is available to buy from Amazon for £24.99

Photographs rendered in Play-Doh

I've normally walked out of a pub quiz with some nuggets of new-found information and I've occasionally left with the victor's prize, but I've never come away with a new hobby. Obviously I'm going to the wrong class of pub quiz, unlike Eleanor Macnair. When she attended a pub quiz hosted by Miniclick by MacDonaldStrand, one round asked the participants to recreate an iconic photograph using Play-Doh. Rather taken by the process, she started doing them at home for a bit of fun. It's grown a bit, with friends requesting specific recreations and a Tumblr dedicated to her work. Now anyone can see her version of August Sander's Pastrycook, Dovima with elephants, evening dress by Dior, Cirque d’Hiver by Richard Avedon reworked in Play-Doh by Eleanor Macnair, or her rendition of Helen Tamiris by Man Ray, whether they're in Yemen or Equador.

Each postcard sized plaque is nothing more than a fleeting creation, however, and Eleanor is not amassing an archive of flour-water-salt dough representations in her living room. She crafts them in under an hour using a pint-glass rolling-pin and a blunt knife from a globally recognised homeware megalith, and they last long enough to be photographed before being broken up and the different Play-Doh colours returned to their respective tubs, ready to be reformed into another image, another day.

Eleanor says that she cringes when she sees people on the Internet debating the value of her project. It is, after all, a bit of fun. But if she can lead lead people to discover new photographers or look again at well known photographs, she's happy. And 'Sometimes it's nice to have the freedom to do something just because.'

Quite frankly I think it should be every photographer's aim to have Eleanor recreate one of their images. They'd be in hallowed company.

You can check out all of Eleanor's Play-Doh photos on her Tumblr: Photographs rendered in Play-Doh.

Can I use this photo I found on the Internet?

(Or, the non-photographer's guide to image use) It's a truth universally acknowledged that articles, newsletters, blog posts, posters, and basically anything involving blocks of text can be improved upon by the addition of an image. When you're writing about the local cycling club's criterium or producing a short introduction to crochet and macrame, you'll probably want some pictures to illustrate events or to explain techniques alongside your race report or detailed how-to. Can you take a look at the site of a local photographer and use some of his images from the cycle race? Can you conduct a Google Image Search for 'crochet' and download some photos of great examples of people's work?

The short answer is always 'No'. Just because someone has posted an image on the Intergoogles, it doesn't mean that it is free for other people to use. You can't use the china in John Lewis' window display without paying for it first, and a photo on Flickr is just the same. Images belong to the people who create them—or in some circumstances, to their employers—so they get to decide how and when they can be used and what the appropriate fee for using them is. We put them on our websites or on photosharing sites because we're proud of our work and we like to display our capabilities, but it's not an open invitation to filch them.

There are a few exceptions to this rule, but until you know better, work under the assumption that every photographer keeps the tightest control over the use of all of her or his images. Being confronted by an angry photographer wielding an invoice for unauthorised image use is not a pleasant situation, so remember: You can't use other people's photos. Mmm'kay?

For completeness, what are these exceptions you talk of?

Some people are happy to licence their images under Creative Commons terms. Creative Commons licences aren't designed as an alternative to traditional copyright, but a complement. They're easy-to-use copyright licenses that allow you permission to use a photographer's images under terms decided by the photographer. One photographer might let you modify and use his images commercially, but another might say that her images must be attributed, cannot be used commercially, and aren't to be modified. However, not all photographers use Creative Commons terms (you'll see it close to the photo if they do) and if there's no evidence of a Creative Commons licence, assume that you can't use the image.

If you receive an image in a press release or it's made available to you from the press section of a website, this will be free to use in the context of the product or situation. For example, when Olympus releases a new camera, it will make a bundle of images illustrating it available to me. Provided that I'm writing about that camera, I'm free to use them in an article. The National Portrait Gallery will supply a selection of images from each of its exhibitions so that if you're reviewing it or publicising one, you have photos to illustrate the article. But, you can only use those photos in relation to the relevant exhibition and they must be attributed under the terms set out by the NPG.

Some news agencies, for example AFP, are happy for you to use their photographers' images non-commercially and for personal use provided that you credit the photographer and agency and link back to the site. But, some agencies aren't. And you wouldn't want to face the wrath of AP or Reuters. Again, unless you're absolutely certain, assume that an image isn't free to use.

But what if you see an image and want to use it? What should you do?

Get in touch with the photographer! Most of us make it easy to send an email: do just that. We don't bite. Mostly. Tell us who you are, why and how you'd like to use a photograph that we've taken, and ask if you can come to an arrangement. The worst that we can say is 'No'.

That's not so hard, is it?

Can you fix the focus on a blurry photo after the fact?

I seem to be on a roll this week, with finding incredibly interesting topics to write about over on Quora. In this case, the question was as simple as it was interesting: "Is it possible to focus an unfocused image with a computer program?".

Answer...

There are many technical challenges with focusing an image after the fact, and it depends heavily on how out-of-focus the original image is. It is possible to do some sharpening that gives the illusion of a photo being in better focus, but actually re-focusing the photo? Not so much.

Here's why...

Take an image like this for example (see the photo on my Flickr stream for a larger version):

The bird in the foreground is in focus (well, more or less), but the plants in the background are not. Now, blurring this photo would be relatively trivial, because you are discarding information.

If your goal was to 're-focus' the photograph so the trees in the background were in focus, however, you're looking at a completely different problem, at least if your photo is taken with a conventional camera (Light-field cameras like the Lytro work differently)... The problem is that you're trying to re-generate information that simply isn't there.

Another example

Let's take another example. This photo, for example (see Flickr for a larger version):

In this photo, you have an extreme macro shot of a fly. You can see the individual facet eyes of the fly, and count the hairs on its back. However, it has very shallow depth of field, and if you look at the legs in the background of the photo, they are just blurry stalks. Now, the technology you are looking for, would somehow magically be able to find out the size, direction, and shape of each of the hairs on the fly's legs that are out of focus in the background.

It stands to reason that this information simply doesn't exist. I took the photo, and I have no idea what colour the hairs were, how many there were, and how evenly they were spaced. This photo is a pretty good document of the fly, of course, but it is physically impossible to recreate information that isn't there - unless you have a data source to base this information on.

On the other hand, Adobe is doing some really interesting stuff with their 'deblur' technology. This isn't the same as focus blur, however; the idea of Adobe's deblurring is to take a photo that was sharp to begin with, but suffers from motion blur. This means that, in theory, a lot of additional information exists in the image, it is just spread over an even surface. As such, it is possible to 'unblur' the image by throwing clever algorithms and a lot of computing power at the problem. Sadly, this is only possible in very limited cases. It's not possible to re-focus an image, but it is possible to evaluate the photo to remove certain image artefacts, much like noise reduction filters etc.

For further reading, check out the vaguely related concepts of Focus stacking (which uses focusing at several focus depths, and calculates an image with deeper depth of field), HDR (which does a similar thing, but for images with various exposures) and, of course, the Lytro camera, which is able to focus after the fact, but struggles with its own problems (including much lower final resolution than we are used to from our digital images).

TL;DR: No, you can't focus an image after the fact.

What is noise?

Photography Fundamentals has reached part 'N', for 'noise'. Digital noise is instantly recognisable in a photo, and we know that keeping your ISO low is the best way to avoid it, but why exactly does it happen? Why does your image quality go down the pan as soon as you touch that ISO dial? What's with all the digital noise?

In 2006, this was the reality of digital noise in photos ...

How does an imaging chip work?

Whether you use a CCD or a CMOS chip in your camera, the basic functioning of an imaging chip is pretty much the same: Imagine millions of tiny little light meters squashed into a tiny little chip the size of a postage stamp. How many million? Well that depends on the resolution of your camera, of course, but if you’ve bought yourself a Canon EOS 700D, you’ve got a 18.5 or so million pixels (of which 18 million are used). All of these pixels are somehow fitted on roughly 22mm by 16mm sized space – yes, that’s about the same area as the button on your average door-bell.

When you take a photograph, there are a set of shutter curtains which move aside – exposing the imaging chip for as little as one eight thousandth of a second – giving the sensor time to measure the light that falls on it. Then, the shutters close again, and the sensor sends the measurements to the camera’s cpu, which does some calculations, and then stores the whole thing as a digital file.

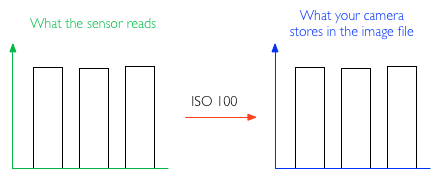

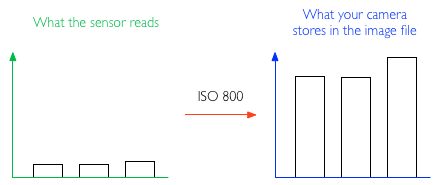

Where does ISO come into it?

Now you know pretty much how an imaging chip works – but where does ISO come into it? Well, all imaging chips operate at the lowest ISO your camera supports – usually ISO 100. In this mode, your camera takes its light measurements from its millions of tiny little light sensors, passes it directly to the brain of the camera, which then stores it.

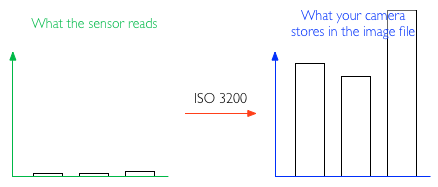

When you crank up the ISO value to, say ISO 400, another step is added to the mix: Your camera still takes the same measurement, but in the CPU of the camera, the measured values are multiplied by 4, to get ISO 400. Or by 8 to get ISO 800. Or by 32 to get ISO 3200. Pretty straight-forward stuff, right?

So, er, Where does digital noise come from?

Silhouette in Concert by yours truly – Also see the full-resolution image for an excellent example of digital noise in photography

Well, think about it: while chips have gotten much, much better in recent years, it’s still a case of 18 million tiny little sensors doing their thing in a space the size of your thumb nail.

The problem is that – as with all precision measuring instruments – they can only be so precise: all of them introduce a degree of measuring inaccuracy. The problem with imaging chips is that they are internally inconsistent, and they are unpredictable.

The inconsistency is a problem which can largely be resolved: The camera can take a photograph, and realises that if one particular pixel always reads a little bit higher than its immediate brethren, it can calibrate so that one pixel is adjusted down to fit better. This calibration is done before the camera leaves the factory, and it’s trivial for camera manufacturers to built-in calibration checks on an ongoing basis – it’s relatively trivial to detect a dead pixel, for example, and then interpolate what its likely value would have been from its surrounding neighbours; and because there are 18 million of them, and we rarely check each individual pixel of a photograph, you’d never know.

The unpredictability issue is different, however; imaging chips are sensitive to temperature, and the act of taking a photograph actually causes the chips to warm up a tiny little bit (there’s a lot of electronics in a camera, after all, including the battery, the CPU, and all the circuitry to tie it all together – all of which generates various amounts of heat). Some cameras have a ‘noise reduction’ feature where they take another photograph immediately after you take a long-shutter-time photograph – but with the shutters closed. The theory is that it should be recording perfect darkness, but in practice it records a variety of readings from all the sensors. By subtracting these readings from the original image, you reduce (some of) the digital noise in an image.

Imaging chips are precise enough that at ISO 100, the differences in readings introduced by digital noise are practically unnoticeable. The problem comes from the multiplication process.

A thought experiment

Imagine you take a photograph of a perfectly grey wall at ISO 100, ƒ/8.0 and 1/30 second exposure time. Three randomly selected pixels now read 100.5, 100 and 102. No problem; it looks great, and the stored values are within 2% of each other – the wall looks like a perfectly even, gorgeous grey wall.

Now, switch the camera settings ISO to 800, ƒ/8.0 and 1/240 second. The final result — in a perfect world — should be precisely the same: We’ve reduced the shutter speed to 1/8 of the original exposure, but the camera will multiply the exposure by 8 because we’ve changed the ISO. The same pixels now read 12.6, 12.5 and 15.5: The margins of error are the same as above. The camera multiplies it all by 8, and stores 101, 100 and 120 to the memory card. Suddenly, there’s a 20% discrepancy between the three values, which becomes very clear in the final image: What you’re seeing here is digital noise.

Now, imagine the same effect at ISO 3200: the pixels read 3.5406, 3.1250 and 5.1875, which the camera multiplies back up to 113, 100 and 166 – a far shot off from the 100, 100, 100 you’d get with a perfect imaging chip.

In reality, the metering tolerances in an imaging chip aren’t that pronounced; but the point is that if you multiply any meter reading by 32 (or much more, depending on how your ISO settings on your camera will take you), you’re talking about pretty serious discrepancies, and some pretty serious noise in your final image.

How can I reduce digital noise in my pictures?

Use as low ISO as you can get away with; Often, it’s better to use a tripod and a remote release cable combined with a longer shutter speed and lower ISO, than trying to shoot free-hand at shorter shutter speeds and higher ISO.

Use shorter shutter speeds; If you can, use shorter shutter speeds – the metering discrepancies will still be there, but less pronounced.

Keep your camera’s insides cool; when you take a lot of photos, you’re introducing more camera noise. Also, if your camera has a ‘Live View’ mode, it sucks battery, and means that the camera’s electronics are constantly working hard – which causes heat, and introduces more noise.

Use noise-reduction software; There’s a few options out there by now, but I've been consistently impressed by the RAW processor built into Lightroom - the before-and-after pics at the top of this article, for example, were processed with Adobe Lightroom. Personally, I quite like a bit of noise in my photos – it makes them look more accessible and ‘real’, I feel – but that might just be me.

TL:DR;

A super-brief summary of all of the above, courtesy of Redditor IAmSparticles:

When you increase the ISO setting on a digital camera, you're increasing the gain and magnifying any faults in the data from the sensor. It's like turning up the volume on a radio station with really bad reception. You can hear the faint signal better, but the static gets louder, too.

The problem is worse on smaller sensor chips (pocket cameras and phone cameras) because all the pixel sensors are packed together in a tighter space, causing more heat buildup and interference between them, and therefore more errors in the output.

Macro << Photography Fundamentals >> Prime lens

Illustrative images in the news: unfair or acceptable practice?

Perusing my copy of the Guardian yesterday afternoon, my eye was caught by the Open Door column where the readers' editor addresses readers' suggestions, complaints, and concerns. Yesterday, Chris Elliott, said readers' editor, was responding to criticism of the use of generic photos to illustrate news stories. As it happens, it is hardly a condition restricted to the Guardian. Before the 'Your Letters' section of the BBC website was so cruelly snatched away from us earlier this year, someone would pipe up every time that 'Drunk Girl' was used to illustrate an article, usually pertaining to binge drinking. At the end of June this year the ever-insightful Liz Gerrard wrote about the endangerment to photojournalists by news publications through the persistent use of generic images.

Back with the Guardian, the dissatisfied reader had asked the question 'How many stories can be illustrated by the same picture?' before now without receiving a response, but had been riled again by the use of a photograph of Angela Merkel gesticulating towards David Cameron that was illustrating an article headlined 'GCHQ surveillance: Germany blasts UK over mass monitoring'. On closer reading, Angela Merkel hadn't come close to remonstrating with David Cameron over the issue; rather, the German justice minister had written to the UK justice secretary and home secretary about things. It was an old image hauled out to give life to the story.

Exactly how fair is this practice?

Elliott responded by stating there are rules to ensure that readers are not misled by the images attached to articles. Specifically: 'Photographs: digitally enhanced or altered images, montages and illustrations should be clearly labelled as such.' Well that's a relief to know. But what about the accuracy of an unadulterated image as it pertains to a story?

He also referred the complaint to a senior sub-editor who is responsible for web content. Her reply was that images are crucial for SEO purposes and all online stories should have one. As a consequence, the use of generic pictures and 'identification shots' to illustrate stories when there are no live images is quite common. Her comment on the image in question is a little perlexing, however: 'I would have thought that a picture of Cameron with Merkel, even if it wasn't live, would be a legitimate way of illustrating a story about the two of them (though [the reader's] complaint seems broader – that she wasn't involved as much as we suggested) – especially if the caption makes no claims it happened yesterday/today.'

So, was it or wasn't it a legitimate use of the image? The senior sub-editor doesn't address this directly. I'm inclined to agree with the reader: the link between the image and the article is too tenuous to be sustainable. But Roger Tooth, the Guardian's head of photography, has a different interpretation:

Surely the point is that an intelligent use of photography means that we don't have to be too slavishly literal. In the case of Cameron/Merkel they are symbols of, as well as leaders of, their respective countries. Pictures are very often used in the Guardian in an illustrative way.

There is something that rankles with me about this comment. Illustrative photography is entirely respectable in certain situations, for example feature articles, but when you're dealing with hard news stories, it's often the image that acts as the reader's lever into it. For this reason, there is a reasonable expectation of accuracy between the photo and the copy. It isn't just a case of luring eyeballs towards an article under less than faithful pretences, but also about conveying an accurate version of events, especially if people don't go on to read the entire piece.

With respect to the specific image mentioned by the Guardian reader, there's something disingenuous about its use because it suggests that the contretempts took place at the highest level when really it didn't. In this case, illustrative picture use doesn't do the story justice. On a more general level, the use of broad 'illustrative images' does little to support the integrity of news publications and even less for the straightened circumstances in which news photographers now find themselves.

Even if editors aren't deliberately manipulating the use of images to support copy, the continued, careless deployment of pictures is only eroding the validity of the press at a time when it can scarce afford to be blase. No, it isn't the most significant obstacle that the press faces right now, but it's one that does have an impact on the public perception of the journalistic craft. And it isn't a difficult fix.

Snapping pictures of pictures. Why?

Over at Gizmodo on Saturday, they asked the question 'What's so wrong about taking photos with an iPad?' I've covered the 'using the iPad as a camera' issue before, so I'm not going to rehash it because that would be boring and actually it rather misses my point because what caught my eye was the image choice to illustrate the article. It was of a young woman using her iPad to photograph impressionist paintings in a gallery. This. This is something that I just do not understand. Not specifically using an iPad to photograph multi-layered, complex works of art, normally exhibited in carefully controlled environments, but photographing them at all. What's the obsession?

It wasn't just the Gizmodo article that got me thinking this; it's something that I've noticed before now in various galleries. Rather than taking time to absorb a piece, to let its colours and its story and its brushwork wash over you, people seem to be intent on looking at it through their three inch—or in the case of a tablet, slightly larger—screens, grabbing a quick photo and moving on from it. I cannot determine any pleasure in that I'm not certain how appreciative it is of the artist's skill and talent.

When you have a Renoir worth millions hanging before you, you pay it the attention it demands and the respect it deserves. That doesn't come from a photo snapped hastily with a miniscule-sensored camera that you'll probably never actually look at again. Even if you do look at your snapshot again, it'll never be able to entrance and captivate you in the same way that the original can. I promise you, a pefectly lit, carefully composed medium format reproduction of a Guardi, a Stubbs, or a Fantin-Latour cannot, in any way, compare to the real thing. So don't think that your iPad-snap or point-and-shoot shot will. You're in a gallery to observe the art, why not do that?

It's almost as if people are taking photos to remind themselves that they've actually seen something, rather than really looking at it and being able to remember it for how glorious it is.

Yes, I suppose that people can waste their time and money photographing delicate, intricate pieces of art with cameras of varying quality in far-from-optimal lighting conditions, rather than gazing at it, enjoying it, and absorbing it if they want to. But can they damn well make sure that they do not stand directly in front it, obscuring my view, when I'm trying to do just that?

How many photos do we take?

According to a piece of research commissioned by SmugMug and conducted by pollsters YouGov, we manage to take a quite astonishing 600 million photos every week here in the UK. Ah-ha, 600 million pictures of kittens, puppies, kiddies, and sunsets. Wondering how they got to that figure? It goes like this.

- The adults questioned for the survey gave the average number of photos they took each week at 19. That doesn't include holidays or special occasions.

- There're 47,754,569 adults in the UK, 30% of whom do not take photos in an average week.

- Seventy per cent of 47,754,569 do take photos. That's 33,428,198 people.

- Multiply 33,428,198 people by 19 photos, and you get just over 635 million.

That's a lot of photos.

Roughly half of those photos are of people, about a fifth are landscapes, and a tenth are of pets and other animals. No one was brave enough to put a figure on how many of those portraits were selfies.

However, 56% of those questioned had lost images because of technical failure, theft, or even human error and almost three-in-ten didn't have a back-up routine of any description. That leaves me wondering, just how valued are images now? Are they becoming so ubiquitous that people aren't too bothered if a swathe of their photographic library suddenly disappeared into the cyber-abyss, or is it more a case that they've never stopped to consider what a catastrophic hard drive failure or a stolen phone might mean? These are slightly different prospects to the threat of fire or flood to printed photos.

The good news is that backing up your photos isn't that difficult and storage is cheap now, too!

Anyway, what do we think? Is 19 a fair number of photos a week? I'd totally skew the figures: I don't think that my potential response of 'Ehm... a few hundred last week,' really counts!

Photographing people who wear glasses

My brother has worn glasses full time for absolutely years, which has meant that I learned how to photograph him wearing them to avoid hideous green glare rather intuitively. I probably did have to think about it at some point, but I don't really remember and now I just seem to do it. That was until this week, when one of the students at Photocritic Photography School piped up and asked me what he should do when he has a portrait subject who wears glasses. For lots of reasons, the answer is never 'Ask your subject to remove them,' so what do you do?

Look at the light

The most obvious problem that glasses will present to you is that they reflect light. Instead of seeing straight through spectacles' lenses and into your subject's eyes, you'll have a unpleasant, usually green-tinged, reflection glaring back at you.

Going back to GCSE physics, we know that the angle of incidence (or the angle at which light will hit someone's glasses) is equal to the angle of reflection (or the angle at which the light will bounce back off the glasses). If light is coming in at an angle of 31° to the normal of your subject's glasses, it'll bounce off at 31° on the other side of the normal*. There's a helpful diagram here.

Consequently, if your light source is too close to your camera the light has a much greater chance of bouncing straight off your subject's spectacles and into your camera's lens. And if the light is coming from straight behind the camera and your subject is looking straight back at the camera, you haven't got a cat's chance in hell. But the upshot is: know where your light is coming from.

* The normal is an imaginary line running perpendicular to the plane of the glasses.

Altering angles

Minimising glare is easiest by one of three means:

- move your light source

- move your subject

- or move your camera

By shifting your light source or yourself, you can alter either the angle of incidence, and therefore reflection, or take your camera out of the firing line. Sometimes, though, your light source can't be shifted (say, when it's the sun) and you moving might not be an option. Then it's down to your subject.

Tilting and turning

If your subject tilts her or his head downwards, just by a few degrees, not by much, it'll be sufficient to adjust the angle of the light and prevent a reflection bouncing back into the camera lens. Or she or he could turn fractionally away from the light source; not enough to wreak havoc with your shadows, but enough to prevent that horrible glare.

When you ask subjects to tilt their heads or change the angle of their shoulders, you might find that their spectacle frames begin to encroach into the view of eye. At this point it becomes a trade-off between reflection obfuscation and frame obfuscation. You need to decide where your tipping point is.

Quit posing

If you opt for more candid shots, you'll be able to capture your subjects looking away or looking down and doing it naturally but still without any nasty reflections.

Go with it

Sometimes, you just have say that the glare is there and it's better to have a photo with a reflection than no photo at all!

Photographing fun - June's photo competition

It's June. June's rammed with some of my favourite events and the weather is supposed to be 'flaming'. Whether or not it will be is another matter, but there's meant to be a whole heap of fun happening. So that's your challenge this month: fun in a photograph. From flying kites on a beach to getting all dressed up for Royal Ascot or covered in strawberry juice, capture a moment of people utterly enjoying themselves.

I bet you can come up with some crackers.

If it's your photo of fun that rocks our world, you'll win yourself a fabulous 12 inch Fracture, thanks to the super people there.

As ever, entries go in the Small Aperture Flickr pool, between today (Thurday 7 June) and Thursday 28 June 2012. Remember: one entry per person, please.

If you've any questions, please get in touch. Otherwise, I leave you with The Rules for your edification.

The Rules

- If you decide to enter, you agree to The Rules.

- You can’t be related to either me or Haje to enter.

- One entry per person – so choose your best!

- Entries need to be submitted to the right place, which is the Small Aperture Flickr group.

- There’s a closing date for entries, so make sure you’ve submitted before then.

- You have to own the copyright to your entry and be at liberty to submit it to a competition. Using other people’s photos is most uncool.

- It probably goes without saying, but entries do need to be photographs. It’d be a bit of strange photo competition otherwise.

- Don’t do anything icky – you know, be obscene or defame someone or sell your granny to get the photo.

- We (that being me and Haje) get to choose the winner and we’ll do our best to do so within a week of the competition closing.

- You get to keep all the rights to your images. We just want to be able to show off the winners (and maybe some honourable mentions) here on Pixiq.

- Entry is at your own risk. I can’t see us eating you or anything, but we can’t be responsible for anything that happens to you because you submit a photo to our competition.

- We are allowed to change The Rules, or even suspend or end the competition, if we want or need to. Obviously we’ll try not to, but just so that you know.

If you've any questions, please just ask!

Triggertrap goes Mobile!

Triggertrap for mobile

When Haje and the Triggertrap team came up with Triggertrap v1 and Triggertrap Shield for Arduino, I thought that was all manner of groovy. The idea of a universal camera trigger rocks, and they were dead proud of themselves. But being crazy inventor-and-developer-types, they weren't quite content with that. They wanted to push things a bit further and see what else they could do. So after a lot of head-scratching, question-asking, code-writing, testing, code re-writing, and more testing, they're excited to unveil Triggertrap Mobile.

It's a camera triggering facility that you operate from your iPhone. That might sound a bit prosaic, but it's far more exciting than that. (And really, we live in an age when we think that using a handheld device that allows us to communicate with someone on the other side of the globe via voice, image, or text to trigger a piece of equipment that produces a digital image is mundane?)

Sure, you can use Triggertrap Mobile with your iPhone, which is pretty awesome, but team it up with the Triggertrap dongle (oh God who invented that word because it makes me snigger every time I read, hear, or say it) and your dSLR or advanced compact camera and you are on to something really exciting.

Time-lapsing

Time-lapses are fabulous and wonderful just as they are, and of course you can use Triggertrap Mobile to produce a time-lapse with your camera, but it also lets you do some very cool things with them; try distance-lapses and eased time-lapses. Distance-lapses and eased time-lapses–you what?

Let's start with the distance-lapse. You can use Triggertrap Mobile to set up your camera to take a photograph at regular distance intervals, for example, every 100 metres. Say you're on the top deck of a bus, recording your journey through a city, you won't end up with a glut of photos from when you're stuck in a traffic jam; similarly, as the bus speeds up, so will the rate at which photos are taken. Stop altogether and so does the Triggertrap.

As for eased time-lapses, these are time-lapses where the interval between each photo taken can be altered. With a traditional time-lapse the interval is set, so it moves at a given speed. An eased time-lapse, on the other hand, can be made to look as if it is speeding up, or slowing down, or both, by controlling how often a photograph is taken. Triggertrap mobile will let you do just that with five different acceleration profiles, spanning from 'mild' to 'brutal'. You can ease in, ease out, or both.

Multiple triggering options

What made Triggertrap v1 so exciting was its ability to allow you to trigger your camera just about any way that you could think of. Carrying that over to an iPhone might be a bit beyond the realms of possibility right now (but I wouldn't bet against Apple and Team Triggertrap), so they've given you 12 different camera-trigger options to keep you occupied until then. You can try anything from facial recognition, to a shock sensor, via a motion sensor, a magnetometer, and a sound sensor to take photos. But perhaps you'd rather use the automatic High Dynamic Range (HDR) bracketing option with up to 19 exposures per set and configurable steps between each exposure, or the HDR time-lapse mode, or the Star Trail photography mode. I can see myself playing around with this thing, descending into a fog of remotely triggered images, and emerging days later wondering why I'm hungry.

If you want something a bit more traditional, Triggertrap Mobile will let you operate your iPhone as a remote control for your camera with its cable release mode. There's a bulb mode where you hold the button for long exposures, a timed bulb mode where you press the button the start the exposure and press it again to stop it, and a long exposure mode that'll allow you exposures of anything from one to 60 seconds.

Shutter channels

Triggertrap Mobile has three different channels, which will allow you to control either your iPhone's internal camera, the focus of an external camera, or the shutter of an external camera independently of each other. Or in combination, if you want.

By getting clever with cables and adapters, you can configure Triggertrap Mobile so that you can trigger your camera, your camera and a flash, or even two independent flashes.

This device is like a triggering nirvana.

Introductory video

There's even an introductory video. How groovy!

Availability

You won't be able to beat me to the front of the queue at the iTunes App Store for this because I've been camping out there since I received the PR, but you can get in line behind me. You've two options.

There's the Triggertrap Mobile Free version, which is, well, free and provides you with three of the modes from the Premium version: cable release, time-lapse, and seismic, which responds to bumps, knocks, and jitters. It's compatible with iPhones 3GS, 4, and 4S, 3rd and 4th generation iPod Touches, and the iPad.

Or you can opt for the $9.99 all-singing-all-dancing-doing-to-okey-cokey Premium Version. It's compatible with all the same devices as the free version, but don't forget that you'll need the dongle (snigger) and you might want a cable, too. You can get those from the Triggertrap store.

Now for the inevitable 'Will they be making an Android version available?' question. Well, they've talked about it, but they aren't making any promises. (I'd say try bribery. They're partial to single malt Scotch, boutique gin, and good wine, red or white.)

I can't wait to see what these guys think of next.

This self-portrait was taken by a stranger on the Internet

This (admittedly not very interesting) pic of me was taken with my Triggertrap when someone joined the Triggertrap newsletter.

Today's post is brought to you by the how-bloody-meta-is-this department...

So, I've been playing with different concepts of automating the taking of photos, by using the Triggertrap universal camera trigger I invented.

As part of the upcoming Triggertrap website (it's launching on Monday!), I was working on the updated Newsletter sign-ups, and I had an idea: Wouldn't it be cool if someone signing up for a newsletter triggered the camera?

So that's what I did - Now, whenever someone signs up for the Triggertrap newsletter, it automatically takes a photo of me, sitting at my desk, slaving away. Okay, so it isn't a very interesting photograph, but that isn't the point - it's kind of awesome that my camera is taking photos whenever someone else does something.

If you want to find out how it's done (and if you, too, want to take a photo of me)... Sign up for the newsletter; the explanation is on the sign-up confirmation page. (Pretty sneaky, eh?)