So, you’ve got your exposures down pat, and your framing is getting better by the day. Excellent. What is next? Well, the lovely Andrew Ferguson, who I know via LiveJournal, submitted a couple of photos for critique that illustrate the next logical step forward: Using shallow depth of field in a creative context.

The first hurdle for many photographers is to get stuff in focus in the first place. The next hurdle is to get the things you want to be out of focus, err, out of focus. Awesome. So how do you go about doing that? Well, let’s learn from Andrew:

This photo, which he asked me to take from his overall rather nifty Flickr stream, serves as an excellent example of how you can use DOF to create a multi-layered image.

The eye is automatically drawn to the parts of the photo that are correctly exposed and in focus, whereas the over-exposed background, which is blurry to boot, gets less attention. If this image had been pin-prick sharp all the way, it would not have had any impact whatsoever: The messyness of the people in the background would have seriously detracted from the overall impression of the photograph.

As it stands, I have no idea what the item of jewelry is, or if it means anything. Quite apart from that, the choker the person in the foreground is wearing is vicious-looking, and her black dreaded hair strengthens the impression of a person who has embraced the ‘goth’ lifestyle.

The foreground is rather strongly contrasted with the background, in that it is a very unusual portrait, which can in fact be interpreted in several ways. The two that sprang to mind:

1) The phrase ‘show me your friends and I’ll tell you who you are’ springs to mind with this photo: Instead of showing a full-on portrait of the person who is in focus, the photographer chooses to express her personality through that of her friends, despite the fact that the friends are out of focus.

2) This person is ostracised from her group, and her alternative clothing style, her going-against-the-grain type personality and what comes across as a strong personality is rebelling, but she is paying the prize in the form of loneliness.

If the people in the background had been in school uniforms, or otherwise ‘conformist’ clothing, I would have leaned towards option 2. I believe that this would have made a stronger photograph on an emotional level, too. However, one of the people in the background has blue hair, and the guy standing up seems to have blond dread-locks, which leads me to conclude the 1st explanation.

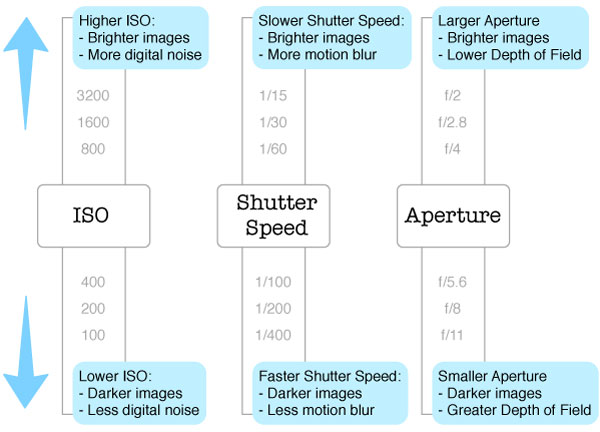

Obviously, this photograph has a lot going for it in terms of ‘showing a little, hiding a lot’, with multiple possible explanations. It is one of the things I quite like about it, but what really makes this image is how it goes about creating this illusion: By using a very large aperture (f/5.6 at ISO 200 and 24mm focal length, in the case of this photograph), there is only very little of the image that is actually in focus: The foreground model’s jewelry and the far-most locks of hair.

In the beginning of this critique, I explained how this image could easily have been completely rubbish, but I hope that the long-ish monologue (which really wasn’t meant to be quite that long, honest) serves to illustrate how the limited DOF has helped pull this image up. It isn’t perfect — If it were, I would have been able to come up with a more consistent story as to what is going on in this image, and why the people in the background are relevant — but it’s a very fine photograph because it allows the viewer to spend some time thinking, making up his/her mind.

If I were to come up with any ways to improve this image, it would be to use different people in the background, perhaps dressed as jocks, nazis, or even as circus clowns. The point is that they need to serve as either a connection or a contrast, and at present they are too similar, yet too different to offer an unified message in the photo.

Bokeh

Shallow DOF and bokeh go hand-in-hand as two rather important concepts in photography, and it is something that is worth keeping in mind when you are working with limited depth of field: The type and quality of the lens you are working with has impact on how the out-of-focus parts of your image look. In Andrew’s photo above, the out-of-focus elements of the image are works of impressionistic art in themselves (See the crop to the left, for example).

Shallow DOF and bokeh go hand-in-hand as two rather important concepts in photography, and it is something that is worth keeping in mind when you are working with limited depth of field: The type and quality of the lens you are working with has impact on how the out-of-focus parts of your image look. In Andrew’s photo above, the out-of-focus elements of the image are works of impressionistic art in themselves (See the crop to the left, for example).

Because of the beautiful out-of-focus qualities, this image works well. If you experiment with the same, but discover that your out-of-focus backgrounds don’t look as expected, try it with one of your other lenses. If you have any cheap lenses, try with them as well – I have a couple of no-brand, cheap-as-chips lenses that are nigh-on useless for any quality photography, but I keep them around beccause they have tremendous qualities for shallow depth of field photography.

The only real way to find out which lenses work and which ones don’t is to experiment, so have a go!

Andrew’s second photograph is this one, of an old motorbike:

… Which I’m not going to say a lot about, other than the fact that it is – yet again – an excellent example of careful use of depth of field.

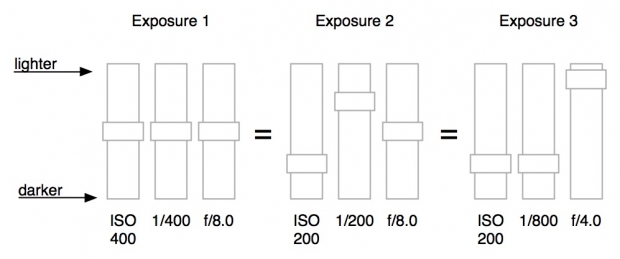

The photo was taken with a Canon Digital Rebel XT and a moody old 24-105 EF lens at 50mm, 1/250 sec, f/4.0 at ISO 400, and I really enjoy what the increased grain at ISO 400 brings to the photograph. With these kind of lighting conditions, you could easily have shot it at 1/125 ISO 200, or 1/60 ISO 100, but the trade-off of faster shutter time and increased grain works very well, perhaps especially because it’s such a gritty topic of photography.

As a personal preference type thing (i.e lots of people would disagree with me), I think the photograph is too bottom-heavy. The sticker on the fork of the bike is disturbing, and while the dirty, oily rag over the bike, combined with the indicator and the reflector of similar, yet different shades of orange really lift the photo, I think there’s too much going on, and too little of a focal point. I like how you’ve used the rule of thirds in the composition of this photo, and it is fine just the way it is.

Because this is my photo critique, however, and because I can’t let a photo stand without a few suggestions for improvement, I’ll go in line with my usual demands: I would have loved this photo to be a lot tighter, and higher impact.

A humble re-crop suggests the following, for example:

This version uses a different approach to the rule of thirds: it breaks the image by using diagonals. The rain-cover is the only things that stands out in the image because it is teh only thing that is straight down. Everything else is at a diagonal: The rain grid in the background, the boke itself, the outline of the rain cover on the left side, etc. As I say, it’s very much a taste thing, and I would most certainly not insist on an approach such as this one, but I feel that the re-crop also highlights the strength of the original photo – the tack-sharp focus on the bike itself, and the out-of focus-ness of the background.

Finally, the out-of-focus areas on the last photo here shows how much of a difference a different lens can have: The small stones in the asphalt and the slats in the rain grid in the background are not particularly aesthetically pleasing in their own right. Everything else being equal, this photo would have looked rather differently if you had taken it with the same lens as the one you used for the first image.

So, what’s the lesson to take home from this critique? Use a limited DOF to offset your foregrounds effectively, but beware of how different lenses can make the background highlights (‘Bokeh’) look very different from each other. Finally, remember that expensive lenses don’t necessarily have a more pleasing out-of-focus experience.

Andrew, thanks for sharing your photos, and good luck with your future photography!

Do you enjoy a smattering of random photography links? Well, squire, I welcome thee to join me on Twitter -

© Kamps Consulting Ltd. This article is licenced for use on Pixiq only. Please do not reproduce wholly or in part without a license. More info.

1) Read your camera’s manual. I know, you’d be hard-pushed for thinking of anything more boring to do than read a camera manual, but I’ve made a habit of reading every manual of every camera I’ve ever had: It’s the only way to fully understand all the features of your camera and where to find them. Except the A-DEP feature (Automatic Depth of Field), of course. Nobody understands the point of that.

1) Read your camera’s manual. I know, you’d be hard-pushed for thinking of anything more boring to do than read a camera manual, but I’ve made a habit of reading every manual of every camera I’ve ever had: It’s the only way to fully understand all the features of your camera and where to find them. Except the A-DEP feature (Automatic Depth of Field), of course. Nobody understands the point of that.

Shallow DOF and

Shallow DOF and