Photography Fundamentals has reached part 'N', for 'noise'. Digital noise is instantly recognisable in a photo, and we know that keeping your ISO low is the best way to avoid it, but why exactly does it happen? Why does your image quality go down the pan as soon as you touch that ISO dial? What's with all the digital noise?

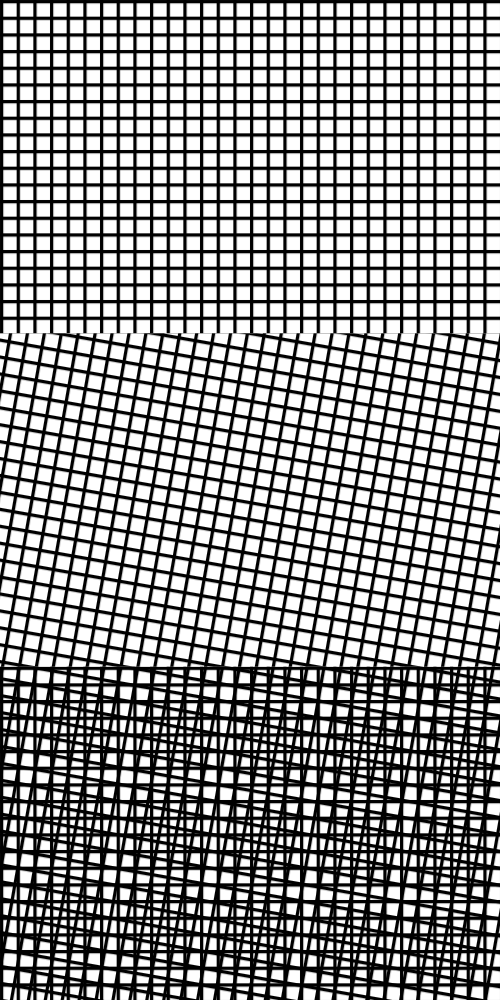

In 2006, this was the reality of digital noise in photos ...

How does an imaging chip work?

Whether you use a CCD or a CMOS chip in your camera, the basic functioning of an imaging chip is pretty much the same: Imagine millions of tiny little light meters squashed into a tiny little chip the size of a postage stamp. How many million? Well that depends on the resolution of your camera, of course, but if you’ve bought yourself a Canon EOS 700D, you’ve got a 18.5 or so million pixels (of which 18 million are used). All of these pixels are somehow fitted on roughly 22mm by 16mm sized space – yes, that’s about the same area as the button on your average door-bell.

When you take a photograph, there are a set of shutter curtains which move aside – exposing the imaging chip for as little as one eight thousandth of a second – giving the sensor time to measure the light that falls on it. Then, the shutters close again, and the sensor sends the measurements to the camera’s cpu, which does some calculations, and then stores the whole thing as a digital file.

Where does ISO come into it?

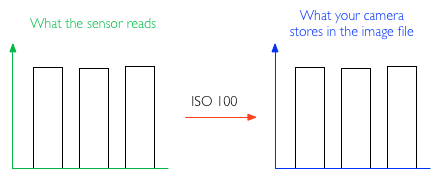

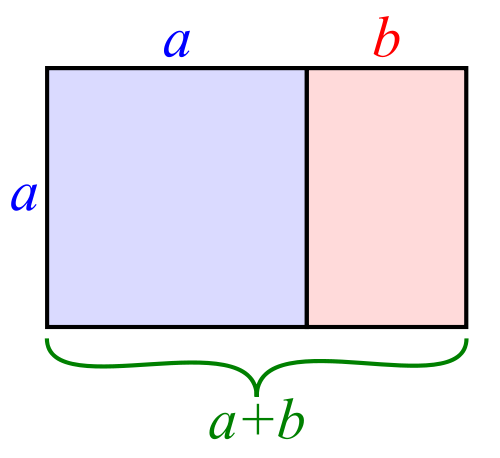

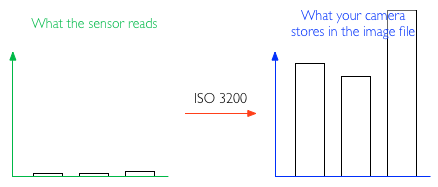

Now you know pretty much how an imaging chip works – but where does ISO come into it? Well, all imaging chips operate at the lowest ISO your camera supports – usually ISO 100. In this mode, your camera takes its light measurements from its millions of tiny little light sensors, passes it directly to the brain of the camera, which then stores it.

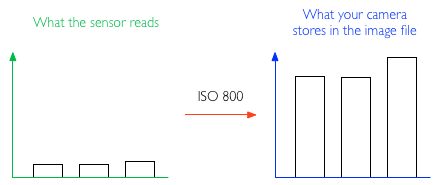

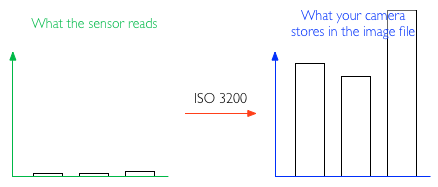

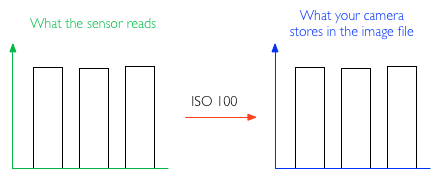

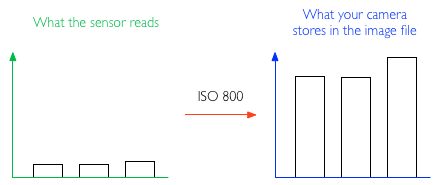

When you crank up the ISO value to, say ISO 400, another step is added to the mix: Your camera still takes the same measurement, but in the CPU of the camera, the measured values are multiplied by 4, to get ISO 400. Or by 8 to get ISO 800. Or by 32 to get ISO 3200. Pretty straight-forward stuff, right?

So, er, Where does digital noise come from?

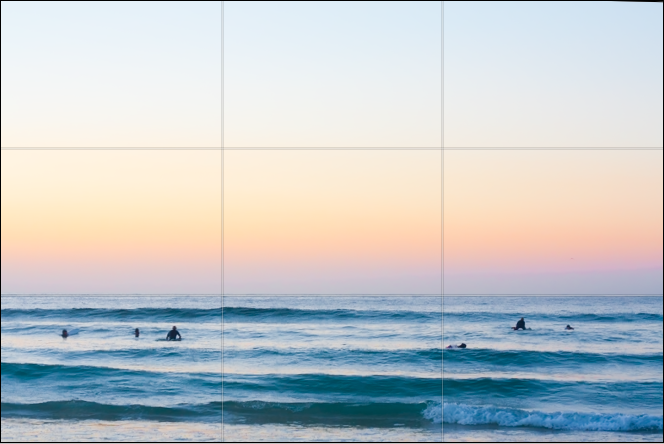

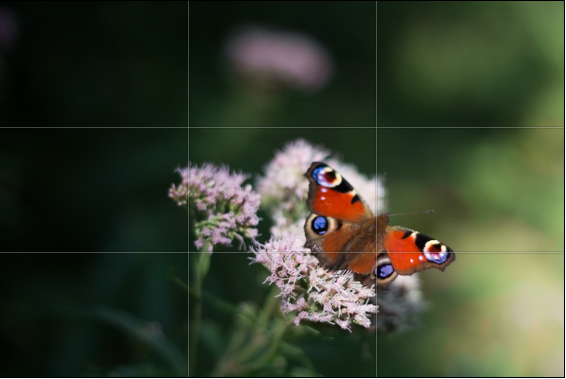

Silhouette in Concert by yours truly – Also see the full-resolution image for an excellent example of digital noise in photography

Well, think about it: while chips have gotten much, much better in recent years, it’s still a case of 18 million tiny little sensors doing their thing in a space the size of your thumb nail.

The problem is that – as with all precision measuring instruments – they can only be so precise: all of them introduce a degree of measuring inaccuracy. The problem with imaging chips is that they are internally inconsistent, and they are unpredictable.

The inconsistency is a problem which can largely be resolved: The camera can take a photograph, and realises that if one particular pixel always reads a little bit higher than its immediate brethren, it can calibrate so that one pixel is adjusted down to fit better. This calibration is done before the camera leaves the factory, and it’s trivial for camera manufacturers to built-in calibration checks on an ongoing basis – it’s relatively trivial to detect a dead pixel, for example, and then interpolate what its likely value would have been from its surrounding neighbours; and because there are 18 million of them, and we rarely check each individual pixel of a photograph, you’d never know.

The unpredictability issue is different, however; imaging chips are sensitive to temperature, and the act of taking a photograph actually causes the chips to warm up a tiny little bit (there’s a lot of electronics in a camera, after all, including the battery, the CPU, and all the circuitry to tie it all together – all of which generates various amounts of heat). Some cameras have a ‘noise reduction’ feature where they take another photograph immediately after you take a long-shutter-time photograph – but with the shutters closed. The theory is that it should be recording perfect darkness, but in practice it records a variety of readings from all the sensors. By subtracting these readings from the original image, you reduce (some of) the digital noise in an image.

Imaging chips are precise enough that at ISO 100, the differences in readings introduced by digital noise are practically unnoticeable. The problem comes from the multiplication process.

A thought experiment

Imagine you take a photograph of a perfectly grey wall at ISO 100, ƒ/8.0 and 1/30 second exposure time. Three randomly selected pixels now read 100.5, 100 and 102. No problem; it looks great, and the stored values are within 2% of each other – the wall looks like a perfectly even, gorgeous grey wall.

Now, switch the camera settings ISO to 800, ƒ/8.0 and 1/240 second. The final result — in a perfect world — should be precisely the same: We’ve reduced the shutter speed to 1/8 of the original exposure, but the camera will multiply the exposure by 8 because we’ve changed the ISO. The same pixels now read 12.6, 12.5 and 15.5: The margins of error are the same as above. The camera multiplies it all by 8, and stores 101, 100 and 120 to the memory card. Suddenly, there’s a 20% discrepancy between the three values, which becomes very clear in the final image: What you’re seeing here is digital noise.

Now, imagine the same effect at ISO 3200: the pixels read 3.5406, 3.1250 and 5.1875, which the camera multiplies back up to 113, 100 and 166 – a far shot off from the 100, 100, 100 you’d get with a perfect imaging chip.

In reality, the metering tolerances in an imaging chip aren’t that pronounced; but the point is that if you multiply any meter reading by 32 (or much more, depending on how your ISO settings on your camera will take you), you’re talking about pretty serious discrepancies, and some pretty serious noise in your final image.

How can I reduce digital noise in my pictures?

Use as low ISO as you can get away with; Often, it’s better to use a tripod and a remote release cable combined with a longer shutter speed and lower ISO, than trying to shoot free-hand at shorter shutter speeds and higher ISO.

Use shorter shutter speeds; If you can, use shorter shutter speeds – the metering discrepancies will still be there, but less pronounced.

Keep your camera’s insides cool; when you take a lot of photos, you’re introducing more camera noise. Also, if your camera has a ‘Live View’ mode, it sucks battery, and means that the camera’s electronics are constantly working hard – which causes heat, and introduces more noise.

Use noise-reduction software; There’s a few options out there by now, but I've been consistently impressed by the RAW processor built into Lightroom - the before-and-after pics at the top of this article, for example, were processed with Adobe Lightroom. Personally, I quite like a bit of noise in my photos – it makes them look more accessible and ‘real’, I feel – but that might just be me.

TL:DR;

A super-brief summary of all of the above, courtesy of Redditor IAmSparticles:

When you increase the ISO setting on a digital camera, you're increasing the gain and magnifying any faults in the data from the sensor. It's like turning up the volume on a radio station with really bad reception. You can hear the faint signal better, but the static gets louder, too.

The problem is worse on smaller sensor chips (pocket cameras and phone cameras) because all the pixel sensors are packed together in a tighter space, causing more heat buildup and interference between them, and therefore more errors in the output.

Macro << Photography Fundamentals >> Prime lens

A spot of pinhole photography may help you break your photographer's block.

A spot of pinhole photography may help you break your photographer's block.