On SLRs, I prefer to go to the opposite extreme of long zooms...

The other day, I received an awesome question from Nick LaRoque via Twitter. He asks an understandable question: "I have a 30x zoom FujiFilm hs10, how do I get the same zoom range from a dSLR?"

It's a fantastic question, and one that is asked every now and again by people who are used to the ludicrous zoom ranges found in the 'bridge camera' segment of large compact cameras. Nick's HS10 packs a 30x zoom, and there are even wilder examples out there, including the deeply impressive Canon Powershot SX30, which squishes a 35x zoom (equivalent of 24-840mm) into a relatively modest package.

How does it work on the ultra-zoom compacts?

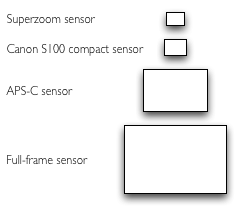

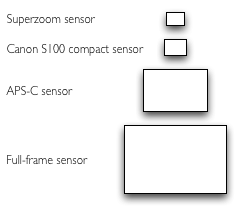

Well, there are a couple of things the compact camera manufacturers do. For one thing, they tend to use rather small sensors; both of the cameras mentioned above use 6.17 x 4.55 mm sensors. That is... Tiny. Compare those numbers to the sensor used in Canon's top-of-the-range compact shooter, the PowerShot S100:7.49 x 5.52 mm; the APS-C sensors used in many digital SLR cameras: 22.3 x 14.9 mm; and the full-frame sensors used in high-end cameras: 36 x 24 mm.

Well, there are a couple of things the compact camera manufacturers do. For one thing, they tend to use rather small sensors; both of the cameras mentioned above use 6.17 x 4.55 mm sensors. That is... Tiny. Compare those numbers to the sensor used in Canon's top-of-the-range compact shooter, the PowerShot S100:7.49 x 5.52 mm; the APS-C sensors used in many digital SLR cameras: 22.3 x 14.9 mm; and the full-frame sensors used in high-end cameras: 36 x 24 mm.

By using tiny sensors, the camera manufacturers can reduce the sizes of the optical elements of the lenses, which makes it viable to create very, very long zooms. That's great news if you like to take photos of things that are far away... Or is it?

The Canon SX30 has a maximum aperture of f/2.7-5.8, and the Fuji is remarkably similar: f/2.8-5.6. The first of those two numbers is not a problem; a 24mm f/2.7 is a reasonably fast lens that is quite versatile. The second number is another story, however. It means that when you are fully zoomed in, you are 'losing' two full stops of light. So: If you were able to take photos at a shutter speed of 1/50th of a second when fully zoomed out, you would have to take your photos at 1/15 when you're fully zoomed in.

That doesn't sound very bad, but the problem is that when you are fully zoomed in, every little vibration of your hands is dramatically amplified. In order to combat that, the rule of thumb is that you need to use a shutter speed that is equal or faster to the inverse of your focal length. I know that sounds a little bit mathematical, but it's easy to grasp with a couple of examples: If you are taking phtoos with your SX30 fully zoomed out, it's the equivalent of a 24mm lens. That means your shutter speed needs to be 1/24 of a second or faster. If you zoom to 100mm, you need 1/100 of a second or faster. And if you zoom all the way in, you're going to need 1/840 or faster. In practice, you're talking 1/1000 of a second, which is a very fast shutter speed indeed.

Now the problem is this: When you are fully zoomed in on the SX30, you are already at f/5.8. If you also need to use a 1/1000 shutter speed, that means that you basically need to be outside in bright sunshine in order to have enough light to be able to take the photo.

The camera manufacturers make a couple of changes to their cameras to make this easier: They introduce optical image stabilisation, which makes it possible to shoot at 840mm at, say, 1/500 or even 1/250 of a second. In addition, they include wide ISO ranges; the HS10 goes to ISO 6400, and the SX30 stretches to ISO 1600.

Of course, optical image stabilisation isn't perfect, and comes at the cost of battery life. Similarly, high ISO comes at the cost of image quality and digital noise.

Ultimately, I'm not saying that superzooms don't have a space in the marketplace, but in my experience, physics (well, optics, really) get in the way of superzoom compacts being as good as they look on paper.

So why can't I get a 35x zoom for my dSLR?

The short answer: You don't want one.

The longer answer is that the superzoom compacts have a 28 mm2 sensor. A full-size SLR sensor covers 1620 mm2. Put differently, the surface area of a full-frame dSLR sensor is nearly 60 times bigger than that of the super-zooms. There are advantages to the bigger sensor: You get higher resolution sensors, less digital noise, and you are able to get more performance out of your expensive lenses. However, it does mean that the lenses have to be physically bigger.

If the sensor surface is 60 times bigger, it stands to reason that the glass that forms the rear lens element of the SLR lens also needs to be 60 times bigger; and this is where the problems start sneaking in. A compact camera lens might weigh about as much as an iPhone; or about 180 grams, which isn't all that much. Multiply that by 60, however, and you've got a completely different picture: suddenly, you're talking about a lens that weighs 10kg (over 23 lbs). It would also have to be around 70 cm (27") long. Finally, on a 840mm lens, the maximum apertures would be absolutely abysmal.

All of this means that if the SLR manufacturers built a lens that covered the 24-840mm zoom range, it would be so heavy that you could barely carry it, so long that you'd struggle using it, so dark that you couldn't actually take photos with it, and so expensive that you'd have to mortgage the house.

So.. No long zooms at all?

There are a few condenders in the SLR market for solid long-zoom lenses. One of the most popular ones is the Sigma 50-500 lens. It has some pretty favourable reviews, but it has its drawbacks as well. The f/4.0-6.3 maximum aperture range is about as good as they come, but if you need the longer end of the zoom range, you could be better served by more exotic lenses; such as the Canon 400mm f2.8, which is a whopping 2.5 stops faster at the same focal length, or the Nikon 500mm f/4.0... Which is also an incredible lens. Don't look at the price tags, though, you might pass out.

Tamron had a go as well, with their 18-270mm zoom lens. That's still only 15x - a far cry away from the 35x record from the compact camera world - but with f/3.5-6.3 maximum apertures, they've done an amicable job with keeping the aperture range relatively low.

Canon has a 18-200mm f/3.5-5.6 lens that only works on crop-frame sensors (known as an EF-S lens). This is because the lens intrudes further into the body of the SLR; by putting the rear lens element closer to the sensor, and designing the lens especially for the smaller sensor, they can keep the amount of glass used in the lens down, which means smaller and lighter lenses. Unfortunately, of course, if you buy one of these, and upgrade to a full-frame sensor later, you can't use your lens on your new camera.

Finally, there's a 18-200mm f/3.5-5.6 from Nikon as well. The review of this lens on DPreview summarises my take on superzooms rather well; "the phrase 'jack of all trades, master of none' springs immediately to mind. It's a lens which delivers somewhat flawed results over its entire zoom range".

In general, the general rule of thumb is that the longer the zoom range of a lens, the more compromises the lens designers had to make in turning the lens into a reality. The real question is; do you really want to invest in a SLR camera body, only to be held back by zoom lenses that become the bottleneck of your image quality?

So, instead, for SLR cameras, it's worth exploring the availability of the opposite extreme. To get the most from that fantastic, huge imaging sensor, don't ruin it all by adding inferior glass. A good prime lens, might perhaps be a good choice... Or you could consider a less extreme zoom lens with a solid performance.

Or, finally, if you're in love with the extreme zoom lens on your superzoom compact camera, perhaps you're the person they invented the genre for. When the time comes to replace it, buy one with a higher-resolution sensor, and keep on snapping.

Photo Credit: The man with the long lens: A Longer lens than Me (cc) by Robbie Shade

Well, there are a couple of things the compact camera manufacturers do. For one thing, they tend to use rather small sensors; both of the cameras mentioned above use 6.17 x 4.55 mm sensors. That is... Tiny. Compare those numbers to the sensor used in Canon's top-of-the-range compact shooter, the

Well, there are a couple of things the compact camera manufacturers do. For one thing, they tend to use rather small sensors; both of the cameras mentioned above use 6.17 x 4.55 mm sensors. That is... Tiny. Compare those numbers to the sensor used in Canon's top-of-the-range compact shooter, the

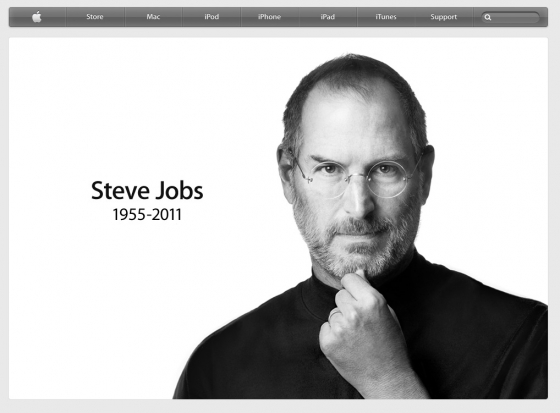

If this was an once-off occurrence, we might have forgiven Apple, but it isn't. There was another piece of software that was of extreme importance; again to the film industry. Shake was aimed squarely at the professional market, and was used for visual effects and compositing - that is, putting the different pieces of digital footage together into a single frame. You know; adding explosions, and adding backgrounds to shots, that sort of thing.

If this was an once-off occurrence, we might have forgiven Apple, but it isn't. There was another piece of software that was of extreme importance; again to the film industry. Shake was aimed squarely at the professional market, and was used for visual effects and compositing - that is, putting the different pieces of digital footage together into a single frame. You know; adding explosions, and adding backgrounds to shots, that sort of thing. Of course, a simple counter-argument to all of the above is "if you don't like the new software, why don't you simply not upgrade"? It is true that this is a workable solution for a while, but the truth of the matter is that software slowly loses its lustre over time: Competitors will bring out features and technology that doesn't exist in the old versions of the software, and without the updates, your software cannot benefit from technology advances that happen in the meantime.

Of course, a simple counter-argument to all of the above is "if you don't like the new software, why don't you simply not upgrade"? It is true that this is a workable solution for a while, but the truth of the matter is that software slowly loses its lustre over time: Competitors will bring out features and technology that doesn't exist in the old versions of the software, and without the updates, your software cannot benefit from technology advances that happen in the meantime.

It's hard to imagine any company that is more mainstream than Apple these days; and the software the company is releasing is reflecting that. Instead of innovating, developing and launching industrial-grade tools for professional users, Apple are ramming home their 'simplicity' approach to things. Which is lovely if you are my mother, but not so much if you are a professional artist of any sort.

It's hard to imagine any company that is more mainstream than Apple these days; and the software the company is releasing is reflecting that. Instead of innovating, developing and launching industrial-grade tools for professional users, Apple are ramming home their 'simplicity' approach to things. Which is lovely if you are my mother, but not so much if you are a professional artist of any sort.

As far as we understand, this means that 500px users can no longer use the 500px Store, although

As far as we understand, this means that 500px users can no longer use the 500px Store, although

So, who dumped who? And why? Did 500px ditch Fotomoto because they think they can do a better job themselves (and, presumably, with bigger profits)? Or did Fotomoto decide they weren't getting the support they required, and were at their wits end with 500px?

So, who dumped who? And why? Did 500px ditch Fotomoto because they think they can do a better job themselves (and, presumably, with bigger profits)? Or did Fotomoto decide they weren't getting the support they required, and were at their wits end with 500px?

If you're anything like me, you'll walk around merrily with your camera slung over your shoulder. After all; you can feel the lens strap against you, right, so you'd know if someone was trying to steal your camera. Right? Right? Well... Yes.

If you're anything like me, you'll walk around merrily with your camera slung over your shoulder. After all; you can feel the lens strap against you, right, so you'd know if someone was trying to steal your camera. Right? Right? Well... Yes.

What is this? - In our NewsFlash section, we share interesting tidbits of news. Think of it as our extended twitter feed: When we find something that get our little hearts racing, we'll share it with you right here! Loving it? Great, we've got

What is this? - In our NewsFlash section, we share interesting tidbits of news. Think of it as our extended twitter feed: When we find something that get our little hearts racing, we'll share it with you right here! Loving it? Great, we've got