If you've been anywhere near a technology magazine in the past few months, you can't have failed to see a series of Tamron adverts, showing off their 'astonishingly compact and leightweight' lens with 15x zoom lens. However, when I was having a peek at the advert, I started wondering what, exactly was going on here.

The advert in question is this one:

Now, don't get me wrong, this is a lovely photograph. But I can't help but wonder whether we're all victim of somewhat false advertising here. There are a whole load of things wrong with this photographer, and as an observant student of photography, I'm sure you can spot at least some of them. Take a close look at the image, and think like a photographer - what are you seeing?

Depth of field

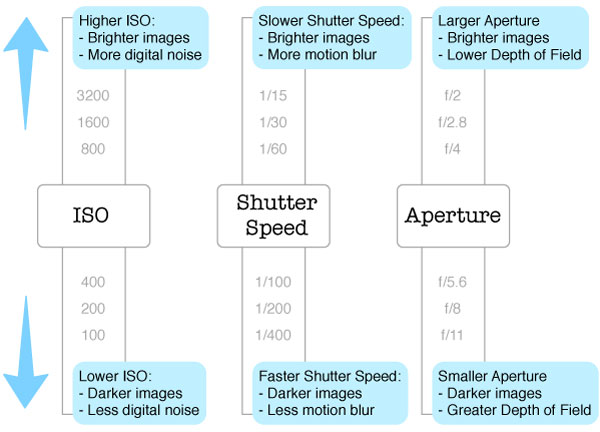

One of the problems I had with this photograph, are the claims about zoom length and depth of field. The two photos are a wide shot and a very up-close photos, and since this is a 18-270mm lens, it stands to reason that Tamron have taken one photo at each of the focal lengths. So, that means that the widest possible aperture the main photo could have been taken at, is f/6.3 (this is a f/3.5-6.3 lens after all). As such, the top photo would have been taken at 270mm and f/6.3.

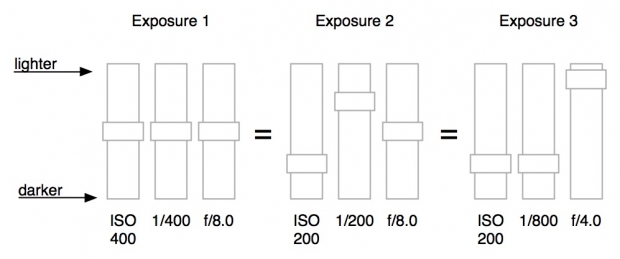

The shadow and highlight on the adult's arm, along with the highlight portion on the boy's arm would indicate that the light is coming from above and left in this photograph. Lovely; but that leaves us with some questions. If we follow the 'sunny 16' rule, this photo would have to be taken at ISO 100 with 1/100th of a second at f/16.

However, there's a very distinct shallow depth of field thing going on, which leads me to believe that this image will have to have been taken wide open - at f/6.3. That's entirely possible, of course, but then the camera would have to be shooting at 1/4000th of a second or thereabouts. No problem, but there appears to be some motion blur on the droplets falling off the oar in the background - indicating that this image will have been taken with a shutter speed of 1/200 or less.

Of course, all of this is possible if they used a Neutral Density filter (in this case, to get from 1/4000 to 1/200, you'd need a ND4 filter or thereabouts) when taking this photo, but as far as a like-for-like comparison goes, that seems a little bit weird for an entry-level consumer lens.

Another argument for why this photo doesn't quite stack up in my mind, is that for this particular lens, you only have to focus up to about a 30ft / 10m distance. After that, you've focused to infinity, which means that even at f/6.3, you actually have pretty decent depth of field. If the top photo is taken from the distance implied by the bottom photo, I'd say that something really curious is going on in these shots: To me, it looks that the distance to the boat is about 10 meters - and if that is true, then the picture is a physical impossibility without extensive photoshopping.

Or rather: I can't really see how a 270mm f/6.3 lens could have taken this photo from the distance the bottom image would imply - especially considering how the boy is perfectly in focus, whilst the boat just in front of him, and the paddle just behind him is out of focus.

If you ask me, it looks as if the photo was taken from much closer than the inset photo claims, the lens blur on the foreground (on the boat) is genuine, whereas the person in the background has been blurred in Photoshop, after carefully applying a mask around the boy. That would certainly explain why there doesn't appear to be any further depth of field fall-off between the man's elbow / paddle and his face - they all seem to be blurred the same amount, which seems unlikely if the photo was taken in the way it is implied

Lighting

The other thing that I find weird in this photograph, is how it looks like the lighting is quite different in the two photos. If you look at the smaller, inset photo, you can see that the life vest the boy is wearing is significantly brighter than his face. On the main photo, however, we are getting remarkable detail and dynamic range in his face.

In fact, the fact that we have perfect definition in the directly sunlit arms of both the people in the photo is astonishing; you'd expect a lot less definition in the shadows in this image... Which makes me believe that this photo has either been through some rather extensive photoshopping to lighten the shadows (nothing wrong with that...) or that a reflector was used to achieve the top photograph.

Again, of course, there's nothing wrong with using a reflector, or photoshopping a photo to make it look better, but I can't quite help but think that whatever is going on here, it would take some expert photoshop or lighting skills to get that much detail out of the photo - and if that is the case, is it a honest comparison between the two shots?

No help from Tamron

Of course, I wanted to find out for myself how these photos compared to their originals, so I e-mailed Tamron back in May to get my hands on higher-resolution versions of the photos used in this advert. Back then, I received an out-of-office e-mail from their press office, but I never received a reply to that e-mail, nor to any of my other enquiries. A shame; I think it could have been really interesting to see how far off I was in my 'photo forensics'.

What can you learn?

Anyway - the point of this article isn't to point fingers - it is entirely possible that Tamron's photos are entirely above board, and that the photos shown are direct-out-of-the-camera versions of photos taken with the Tamron 18-270mm lens...

The point I'm trying to make is that you can learn an incredible amount about a photograph by just looking at it, without having any additional information about the equipment used. The key to learning something from this exercise is to ask the right questions, and apply everything you know about photography to the image to 'reverse engineer' how it was taken.

I made a habit of analysing photographs I've seen in magazines a long time ago:

- Where does the lighting come from? Is it natural lighting, flood, or flash lighting? How is the light managed / adjusted / reflected / diffused?

- What is the shutter speed and aperture likely to be?

- What angle was the photo taken from?

- What focal length lens was the picture taken with? Was it taken with a telefocus or a wide-angle lens?

- What digital enhancements were done on the photo before it ended up on print?

By spending 30 seconds on any photo you see around you, you can train yourself to become a better photographer, even when you are miles away from your photographic equipment!

Horizon on the upper third; shoreline on the lower third. Perfect!

Horizon on the upper third; shoreline on the lower third. Perfect!