A few years ago, I was part of a creative arts project in Arizona and southern Utah, where we did a lot of work with Native American people — a ‘world through our eyes’ type thing. One of the things that was brought up when we were dealing with more traditional tribes, was that we weren’t to take any photos. Perhaps surprisingly, some people believe that when you take photos of them, you steal a part of their soul.

Religions and superstitions aside, I think it’s a good way to look at portraiture. Stealing souls is a bit harsh, but if your photographs don’t at least borrow a little bit of soul from your subjects, I believe you may have failed as a photographer.

For this article, I’ve chosen to do a critique some of the photos submitted to me by Isaac – an USC film student with a passion for photography. His images illustrate very well how adding a touch of feel (or soul, if you will) can lift your portraiture.

With his photos, Isaac included a note. Now, normally, I don’t pay much heed to what people say about their photos: if they can’t stand on themselves, they aren’t worth critiqueing. In this case, I made an exception: Essentially, Isaac is begging to be kicked to the kerb:

Compliments are nice, but for someone in my position they are useless – I’m a newb and I need people to tear my work apart so that I can improve. Please, please, I beg you, be as harsh as you possibly can. Thanks.

… Which I would have done, if his pictures were actually bad. Luckily, they aren’t. Without any further ado…

Isaac’s first photo has is titled ‘arms’:

At first, I wasn’t quite sure what to feel about this photo. It’s terribly messy, and you can’t actually see anything of what is going on. I’m also not a big fan of the photographer being reflected in the camera, on a general basis. In this one, however, the expression of the photo comes together in a wonderful way.

To me, it seems as if this photo is taken in a changing room. The girls are performers, preparing to go on stage, perhaps. The girl on the left is showing a slightly worried expression, and is looking at the photographer through her hand in the mirror, while the other model is completely obscured in what seems like a dancer’s pose. Is she snapping her fingers? Is she fixing her hair?

The tension in this photo — and much of its soul — comes from the tension in the photograph. The photographer is intruding into a world where he doesn’t belong, and the way the models obscure their own face almost seems as a defensive gesture, even though the body language of both girls are very open.

Along with the tension and the colour repetition (there is only one accent colour, and it’s pink. It’s reflected in the light source, on the photographer’s shirt, in the left girl’s hair band and the right girl’s top), the thing that intrigues me about this photo is that you can follow the path of the light. Take the left model, for example, you can see her head, then her head in the mirror. You can then follow the light beam through the hand which is obscuring her face, which you can also see in the mirror, and then into the photographic lens. As a photographer, this multi-layered self-referential image is very appealing and exciting to me.

On a technical level, I would probably have tidied the image up a little bit. Darken the background more, black out the writing (on the mirror? On the photographer’s shirt?), and get rid of everything to the left of the left model, and to the right of the right model. Once that has been done, it will increase the focus of the photograph.

The final thing which makes this image really work for me, is that if anyone has had their soul ‘stolen’ in this image, it’s the photographer himself. The models are obscured, and the only person who you can connect with (despite the camera stuck in front of his face), is the person taking the photo.

A powerful, cheeky, and inventive photo indeed.

In Isaac’s second photo, entitled Mika, he’s using a different set of techniques:

In a way, I really wanted to read a lot of meaning into this photo, but there’s something about it which doesn’t quite allow that for me. The car in itself is delightfully dilapidated, and the dirt, decay and entropy it and the background represents makes a fantastic backdrop for telling a story.

The model is beautiful, and very well captured on your behalf. The problem I have with the image, however, is that she just doesn’t look quite right in her circumstances. The way she is dressed and posed gives the photo an impression of ‘look! an old car! let’s take a picture on it’. If she was dressed differently, there would have been an opportunity for a whole series of different stories worth telling. Dressed very beautifully and glamorously, it could be a story of being lost / being out of ones element. With more frizzy hair, perhaps a scruffy, stained t-shirt, and with dirty, bare feet, it could be a story of despair, loss, and hopelessness. Open the bonnet and make her a spanner monkey, with some creative lighting and perhaps with a streak of oil on her cheek, and you have a classic ‘sassy mechanic’ shot. Sat in the car, perhaps in a bikini, or even nude, it’s a different story again.

I think this photo is an excellent counter-example of the above. All the elements are there: The model is attractive and sultry, the background looks bloody amazing and is well cropped, and the lighting is quite beautiful. However, you haven’t captured the ‘soul’ of the photo, and we’re left with an image that, whilst interesting to look at and quite pretty, doesn’t move me at all.

That doesn’t meant that the photo is beyond saving, of course — technically, it’s close to perfect (the only thing I’d address is the lighter area in the top right of the image. Getting someone to stand in the way of the sunlight, setting up a screen, or just cropping / editing it out in Photoshop would take care of that), and as I say, both the model and the setting have a lot of potential.

… Which semi-elegantly leads me to the last image of today’s critique. Another photo of Mika:

This photo fills me with wonder. What’s going on? Why is she stood in the sunshine in front of a half-pointed wall? Her eyes are kind of closed. Is she tired? Is she reacting to the sun? Is she on drugs? She does look sort of suspicious. Is she trying to hide from something or someone? Is she suspicious herself, of does she mistrust the photographer? Is she angry at the photographer?

With an initial impression like that, you’re bound to catch the attention of onlookers, which is a great start in the battle towards getting a photo noticed.

On a technical level, I think I’m not too fond of the sharp side-light. The shadow of her eyelashes on her nose is not particularly flattering, and while it does look as if you’ve used a reflector to lighten up the ‘dark’ side of her face (did you? Or is it merely light reflected back off the wall? It doesn’t look as if there is enough wall surface for that amount of light reflection), it isn’t quite enough. The main thing I have a problem with from a technical point of view, is that even in this photo, it’s possible to see that the model has absolutely gorgeous eyes. We want to be able to see them properly! A fill-flash would definitely have come in handy here. While you’re at it, perhaps a little bit more light on the wall behind the model as well — the sharp contrast between the white and the light olive colours carry this image — use it!

Right, with all that out of the way, let me say that this image is bloody good. Just like the first image, it harbours a lot of emotion and it tells (or rather, hides) a story. The light is low on the horizon, which to me says ‘evening’ or ‘morning’. Based on the make-up, I want to think evening. Or is it morning? Is her tiredness because she’s been out all night? But she doesn’t sweaty or messy enough to be out all night…

Obviously, I haven’t got the faintest idea who the model is, nor what her relationship to the photographer is, nor what her personality is like. Conflicting images of misspent youth, worry, intelligence, drug abuse, perhaps. Whatever it is, this photo oozes feeling, emotion, and — yes — soul.

Right, I do realise that this is the least useful critique I’ve done on here in a long time. There’s just something that really works in this image, and it drives me spare that I can’t put my finger on what it is. I have an idea I’ll come back to this image many times in the future, and every time, I’ll be left wondering. It’s a sign of unbridled greatness. Sort out the technical details, and you’re on to a proper winner. Thank you so much for sharing this.

Can anybody else add anything to the critiques? Do you agree? Not sure? Do you completely disagree? Well that’s what the comments are for.

Do you enjoy a smattering of random photography links? Well, squire, I welcome thee to join me on Twitter -

© Kamps Consulting Ltd. This article is licenced for use on Pixiq only. Please do not reproduce wholly or in part without a license. More info.

Some of my favourite instructables include Photographing in the Ultraviolet spectrum, how to make a macro attachment for a digital compact, converting your Holga to a 35mm (more about holgas), a pretty good guide to creating QuickTime VR panoramas (although, if I were you, I’d use CleVR instead…), a superb guide to taking infra-red photos with your digital compact cameras, building a light tent.

Some of my favourite instructables include Photographing in the Ultraviolet spectrum, how to make a macro attachment for a digital compact, converting your Holga to a 35mm (more about holgas), a pretty good guide to creating QuickTime VR panoramas (although, if I were you, I’d use CleVR instead…), a superb guide to taking infra-red photos with your digital compact cameras, building a light tent. The instructable to introduction to band photography is decent as well, and well worth a look – but it’s not as good as Photocritic’s discussions of the same, obviously :-)

The instructable to introduction to band photography is decent as well, and well worth a look – but it’s not as good as Photocritic’s discussions of the same, obviously :-)

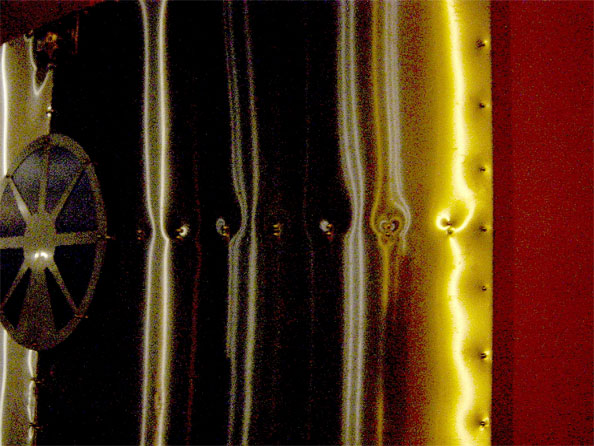

The two key secrets to smoke photography is inverting the image, and using gray smoke. Say what now? How does that work? Well, Graham explains: “It’s quite a simple technique, really. All you need to concentrate on when you are taking the photos themselves, is getting good images of the smoke. The colours are generated digitally at a later stage.”

The two key secrets to smoke photography is inverting the image, and using gray smoke. Say what now? How does that work? Well, Graham explains: “It’s quite a simple technique, really. All you need to concentrate on when you are taking the photos themselves, is getting good images of the smoke. The colours are generated digitally at a later stage.” While smoke in itself can be an interesting subject matter, Graham points out that in his photos, the smoke itself isn’t the subject matter, it is merely the tool used to create unusual photographs: “I am not trying to create pictures of smoke; I am trying to create pictures by using smoke”. This approach means that you have full creative licence to do what you want to manipulate the smoke as much as necessary — the only thing you have to worry about is getting an impressive final result.

While smoke in itself can be an interesting subject matter, Graham points out that in his photos, the smoke itself isn’t the subject matter, it is merely the tool used to create unusual photographs: “I am not trying to create pictures of smoke; I am trying to create pictures by using smoke”. This approach means that you have full creative licence to do what you want to manipulate the smoke as much as necessary — the only thing you have to worry about is getting an impressive final result. When you are photographing, it is easiest to let the smoke rise on its own volition. Instead of trying to manipulate the incense stick, try wafting some motion into the air to disturb the even plume. Alternatively, you can try to create interesting shapes by making the plume turbulent: try introducing a ruler, an upturned spoon, or a sheet of paper into the plume to alter its shape and ‘feel’.

When you are photographing, it is easiest to let the smoke rise on its own volition. Instead of trying to manipulate the incense stick, try wafting some motion into the air to disturb the even plume. Alternatively, you can try to create interesting shapes by making the plume turbulent: try introducing a ruler, an upturned spoon, or a sheet of paper into the plume to alter its shape and ‘feel’. Personally, my best smoke photos were taken with a 2000W Bowen studio flash light with a humongous soft-box fitted on the front. I prefer this solution because the softbox gives even lighting, but it can be difficult to limit where the light goes, so the above-mentioned limitations of “no light on your background or camera lens” can get tricky. I find that if you put the soft box really close to the smoke, you can get excellent results. Having said that, my smoke photos aren’t nearly as good as Graham’s, and he uses a different approach: “For all practical purposes the light used to expose the image comes from one studio flash unit fitted with a snoot and placed at the side or behind the smoke. I realise that not everyone has one of these units, but an off camera flash gun fitted with or placed beside a baffle to protect the background from direct light works just as well.”

Personally, my best smoke photos were taken with a 2000W Bowen studio flash light with a humongous soft-box fitted on the front. I prefer this solution because the softbox gives even lighting, but it can be difficult to limit where the light goes, so the above-mentioned limitations of “no light on your background or camera lens” can get tricky. I find that if you put the soft box really close to the smoke, you can get excellent results. Having said that, my smoke photos aren’t nearly as good as Graham’s, and he uses a different approach: “For all practical purposes the light used to expose the image comes from one studio flash unit fitted with a snoot and placed at the side or behind the smoke. I realise that not everyone has one of these units, but an off camera flash gun fitted with or placed beside a baffle to protect the background from direct light works just as well.” Now that you’ve captured the photos, it’s time to take it to your digital darkroom. Crop your image to a composition that works for you, and then use levels or curves to adjust the contrast of your photos. You’ll want to make sure that the background is completely black (hold the alt key while adjusting the black-point levels slider in Photoshop, it gives you a preview of what you’re actually doing), so it turns into a pure white when you invert the image.

Now that you’ve captured the photos, it’s time to take it to your digital darkroom. Crop your image to a composition that works for you, and then use levels or curves to adjust the contrast of your photos. You’ll want to make sure that the background is completely black (hold the alt key while adjusting the black-point levels slider in Photoshop, it gives you a preview of what you’re actually doing), so it turns into a pure white when you invert the image. The best place to go for some inspiration are

The best place to go for some inspiration are

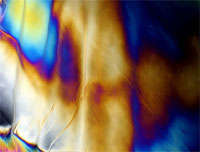

Imagine now, if you will, what would happen if you were to put another set of bars, rotated 90 degrees in relation to the first set of bars. In theory, none of the ice-cream sticks would get through, right? Well, that’s how Polarizer filters work, too. Of course, no polarizer filter is perfect, so some light will always get through, but the vast bulk of light is filtered out.

Imagine now, if you will, what would happen if you were to put another set of bars, rotated 90 degrees in relation to the first set of bars. In theory, none of the ice-cream sticks would get through, right? Well, that’s how Polarizer filters work, too. Of course, no polarizer filter is perfect, so some light will always get through, but the vast bulk of light is filtered out. Cross-polarization exploits this by placing objects made of some types of plastic between the first and the second polarizer. For this particular set-up, you’ll want to put your first polarizer in front of the light source, then your plastic object, and then use the second polarizer in front of your lens.

Cross-polarization exploits this by placing objects made of some types of plastic between the first and the second polarizer. For this particular set-up, you’ll want to put your first polarizer in front of the light source, then your plastic object, and then use the second polarizer in front of your lens.

Shallow DOF and

Shallow DOF and

The first proper portrait I did was April this year. The friend in question was highly suspicious of my abilities, hugely hungover and rather lined and crumpled (he used to smoke 20 a day and had recently given up). I only had a compact digital camera with me at the time and the light was fading rapidly. I put it into sepia and made it look old fashioned because he’d insisted he didn’t want to look ginger on it, the awkward bastard. He was actually quite chuffed with his portrait and has merrily posted it on websites to show people. More importantly though, it stands as a record of how crumpled he actually was, and now, 9 months on, I’ve taken some more photos where he looks a lot less crumpled and he’s pretty pleased about this. This is what giving up smoking does for you.

The first proper portrait I did was April this year. The friend in question was highly suspicious of my abilities, hugely hungover and rather lined and crumpled (he used to smoke 20 a day and had recently given up). I only had a compact digital camera with me at the time and the light was fading rapidly. I put it into sepia and made it look old fashioned because he’d insisted he didn’t want to look ginger on it, the awkward bastard. He was actually quite chuffed with his portrait and has merrily posted it on websites to show people. More importantly though, it stands as a record of how crumpled he actually was, and now, 9 months on, I’ve taken some more photos where he looks a lot less crumpled and he’s pretty pleased about this. This is what giving up smoking does for you.

There was a point to this post (I’ll get there in the end, honestly) and it was that as Christmas has just been and gone there are a lot of people out there who have been let loose with new cameras, or new lenses for old cameras. Basically, the world is not a safe place right now if you’re nervous about having your photo taken. However, for all those new camera owners, you might get a photo worth sticking on your wall if you try out these five things:

There was a point to this post (I’ll get there in the end, honestly) and it was that as Christmas has just been and gone there are a lot of people out there who have been let loose with new cameras, or new lenses for old cameras. Basically, the world is not a safe place right now if you’re nervous about having your photo taken. However, for all those new camera owners, you might get a photo worth sticking on your wall if you try out these five things:

For this issue of the Photocritic Photo Critique, we’re going far afield! Joel Legassie is a Canadian who is currently living in Japan, and is an avid photographer. His photos are sharp, stylish, and striking… So can we offer him any advice?

For this issue of the Photocritic Photo Critique, we’re going far afield! Joel Legassie is a Canadian who is currently living in Japan, and is an avid photographer. His photos are sharp, stylish, and striking… So can we offer him any advice?

The main beef I have with this photo is that it is a little haphazardly framed. I can’t work out why you decided to put the flowers in the middle of the frame, with the ‘broken’ leaves towards the side. Personally, I have a dirty, dirty fetish, which is (I can tell you all can’t wait to find out…) to crop in tighter. Always closer in to the action. It’s a matter of taste, of course, and I fully respect if you decide to make a different choice, but if I had taken this photo, I would have gone in a lot closer, much like the mock-up crop shown to the right.

The main beef I have with this photo is that it is a little haphazardly framed. I can’t work out why you decided to put the flowers in the middle of the frame, with the ‘broken’ leaves towards the side. Personally, I have a dirty, dirty fetish, which is (I can tell you all can’t wait to find out…) to crop in tighter. Always closer in to the action. It’s a matter of taste, of course, and I fully respect if you decide to make a different choice, but if I had taken this photo, I would have gone in a lot closer, much like the mock-up crop shown to the right.

The second thing you could consider is if your cropping makes sense. There’s an awful lot of space at the top and bottom of this image that doesn’t tell a story. Why is it there? Walk, or zoom, in closer to get rid of it, or just chop it off in Photoshop. I’m all for negative space, so in this particular photo, I’d probably go for a square frame – like the crop shown to the right.

The second thing you could consider is if your cropping makes sense. There’s an awful lot of space at the top and bottom of this image that doesn’t tell a story. Why is it there? Walk, or zoom, in closer to get rid of it, or just chop it off in Photoshop. I’m all for negative space, so in this particular photo, I’d probably go for a square frame – like the crop shown to the right. What you are looking at in the white areas, is the ‘burn out’ I started talking about in the beginning of this post. You can actually see it digitally too: Open up your photo in Photoshop, and choose “Levels” from the Image – Adjustments menu. You should see a curve which looks a lot like the one seen to the right of this paragraph.

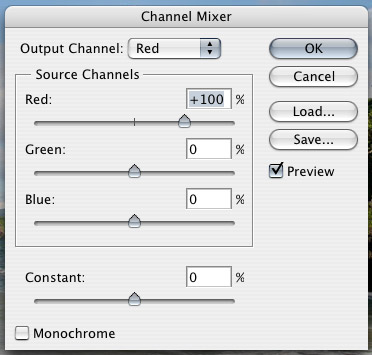

What you are looking at in the white areas, is the ‘burn out’ I started talking about in the beginning of this post. You can actually see it digitally too: Open up your photo in Photoshop, and choose “Levels” from the Image – Adjustments menu. You should see a curve which looks a lot like the one seen to the right of this paragraph. For your particular photo, I don’t think there is a lot of hope of ‘saving’ it… Or is there? I had a play around with it. I turned it into Black and White (

For your particular photo, I don’t think there is a lot of hope of ‘saving’ it… Or is there? I had a play around with it. I turned it into Black and White (

The best way of turning a picture like this into black and white, is to use something called the channel mixer – one of the lovely functions found in Photoshop, or indeed most image editing apps.

The best way of turning a picture like this into black and white, is to use something called the channel mixer – one of the lovely functions found in Photoshop, or indeed most image editing apps.

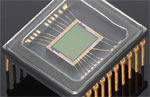

This one falls in the “if you are planning to do this, you have to hate your SLR” category. If you enjoyed our earlier tip about IR photography, you will probably have noticed that many cameras – especially DSLR cameras – have IR filters built into the body. Obviously, that means that you can’t use it for IR photography. Unless you remove the filter, that is…

I wouldn’t dare do it to my own camera, but if you have a destructive streak (or very steady hands), you could follow the instructions posted on

This one falls in the “if you are planning to do this, you have to hate your SLR” category. If you enjoyed our earlier tip about IR photography, you will probably have noticed that many cameras – especially DSLR cameras – have IR filters built into the body. Obviously, that means that you can’t use it for IR photography. Unless you remove the filter, that is…

I wouldn’t dare do it to my own camera, but if you have a destructive streak (or very steady hands), you could follow the instructions posted on