Whenever I read a magazine—which I do, actual dead tree publications, usually involving food, I'm a sucker for food magazines—I always find myself skipping over the pages that are discreetly marked 'Advertisement' towards the top or the bottom of the page, but that look suspiciously similar to editorial content. I don't need the gushing exultations of PR people telling me how wonderful, life-changing, and revolutionary a product is; it's the publishing world's equivalent of the infomercial. I'm far more interested in a reviewer's impartial and honestly held opinions. That's rather the point of buying a magazine or subscribing to a blog.

It sticks in the throat a bit when you realise that some publications are entirely prepared to, and will even solicit the exchange of money to run copy covering products that masquerades as a review. You read what people have to say because you trust them (or in some cases because they provide a cracking laugh), not because they've been paid by a manufacturer or developer to say it. You might expect that some review models or copies would have been provided gratis for the purposes of the review, but that goes with the territory.

The exchange of money is a slightly different prospect.

When the delineation between editorial and advertisement disappears, how do you trust what the publication says at all? Where does real end and the sunshine and rainbows existence of advertising executives start? My throat is currently jammed up like a beaver's dam because that's exactly what happened when Shutter Magazine approached Triggertrap to feature it as its 'Editor's Pick' for September.

For the fee of $2,000, Shutter Magazine was prepared to endorse Triggertrap's Flash Adapter as a monthly 'Editor's Pick', which would include a full page editorial review of the product, a hi-res image of it, and a video review hosted by Sal Cincotta, Shutter Magazine's publisher. I've taken a very close look at Shutter Magazine and nowhere do I see any previous 'Editor's Picks' labelled as advertisements or paid-for content. Furthermore, it was the publication's Advertising Sales person who made the approach, not the editor requesting a product for review.

Thinking this was rather disingenuous, Haje Jan Kamps (CEO of Triggertrap, publisher of Photocritic, and former editor of gadget website T3.com) probed a little further.

Shutter Magazine claimed that the $2,000 fee was primarily to cover the video production costs (having looked at one of the videos, I reckon my grandmother could have done a better job in her living room, but what do I know?) but it would be possible to secure a half-page 'review', without a video, for $600.

'When I was an editor,' says Haje Jan Kamps, former editor of gadget website T3.com, 'running advertising as editorial on my website would have been completely unacceptable, and for good reason: It would completely have ruined the reputation of the site. The importance of the "Chinese wall" between editorial and advertising cannot be overstated. After all, who would trust any recommendations from a publication that sells its Editor's Picks to the highest bidder?'

That sums up the situation effectively: the integrity of any publication depends on its impartiality and for its readers to be able to determine what is genuine editorial content and what has been paid for. There's nothing intrinsically wrong with advertising - we'd be lying if we said we didn't want any here on Photocritic; bloggers have to eat, too - but it needs to be obvious and transparent.

We responded to Shutter Magazine's Advertising Sales person, highlighting that we found the practice distasteful and verging on the unethical, and requested a comment from the editor and the publisher. We're awaiting the director's comment, but Shutter Magazine has been keen to point out that the 'Editor's Picks' run in 'a separate section from our monthly magazine, and that we incur video costs. I also made it 100% clear that we're selective over our Picks as well.' Unfortunately, I cannot find any evidence of the 'Editor's Picks' being indicated to Shutter Magazine's readers as advertorial content, and I'm not convinced there's a world of difference between discerning back-handers or indiscriminate ones.

Kamps' opinion is perhaps even more strident than mine: 'It's entirely possible that this is just an over-zealous sales-man overstepping his mark, but in my mind, passing off paid-for content as editorial awards and editorial content is getting dangerously close to fraud.'

We understand publishing and we understand advertising. We wouldn't expect any publication to forego advertising revenue if that's what it needed to put out copy every issue. We just want to know where the fantasty ends and the reality begins and that when a journalist or writer says something, she or he really means it. Shutter Magazine, we're looking at you.

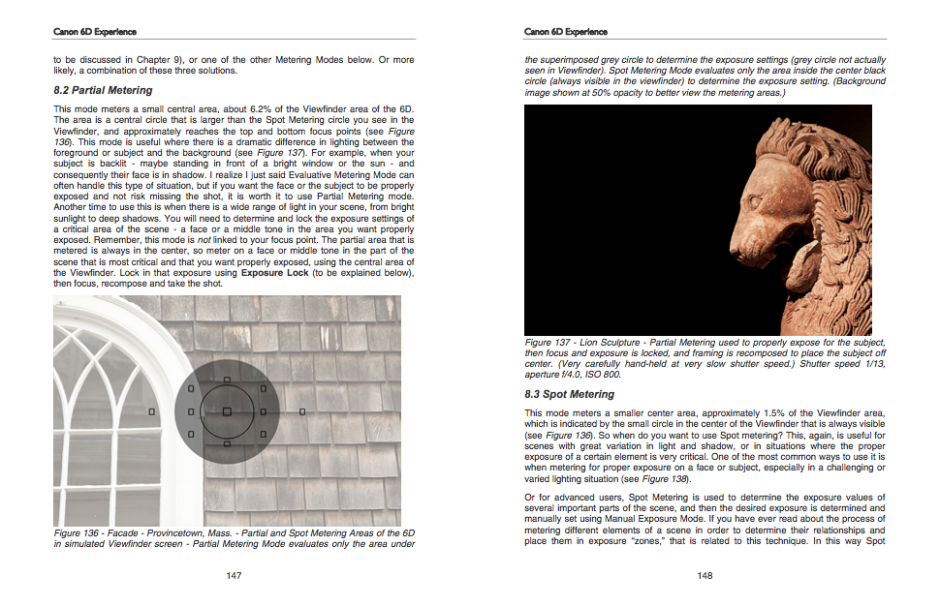

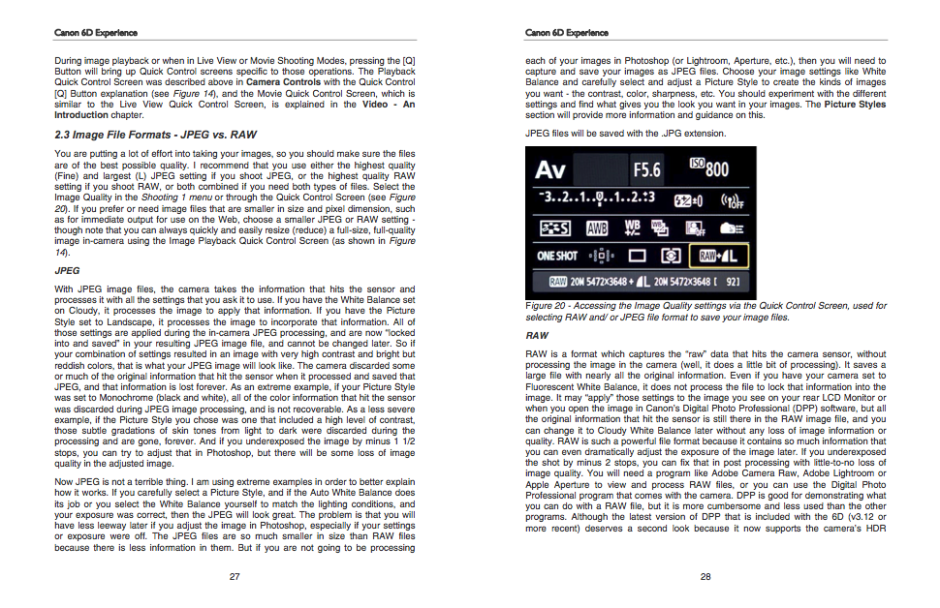

The Canon 6D Experience is part of Douglas J. Klostermann's series of e-book guides to Canon's and Nikon's dSLRs. There are ten Canon books and five Nikon books, ranging in price from $7.99 for guides to the oldest models of camera to $14.99 for the latest cameras. I've been taking a flick through it and seeing how it fits in with my use of my Canon 6D.

The Canon 6D Experience is part of Douglas J. Klostermann's series of e-book guides to Canon's and Nikon's dSLRs. There are ten Canon books and five Nikon books, ranging in price from $7.99 for guides to the oldest models of camera to $14.99 for the latest cameras. I've been taking a flick through it and seeing how it fits in with my use of my Canon 6D.

When Metroprint, a British-based photographic print service, launched its Instagram print service in November last year, I did rather haul it over the coals. For a start, when I first gave it a go, I couldn't order prints direct from my smartphone, but had used a desktop interface, and when this piece of bad design or flawed planning was finally rectified, the interface sucked. I was far from impressed. You can probably tell from

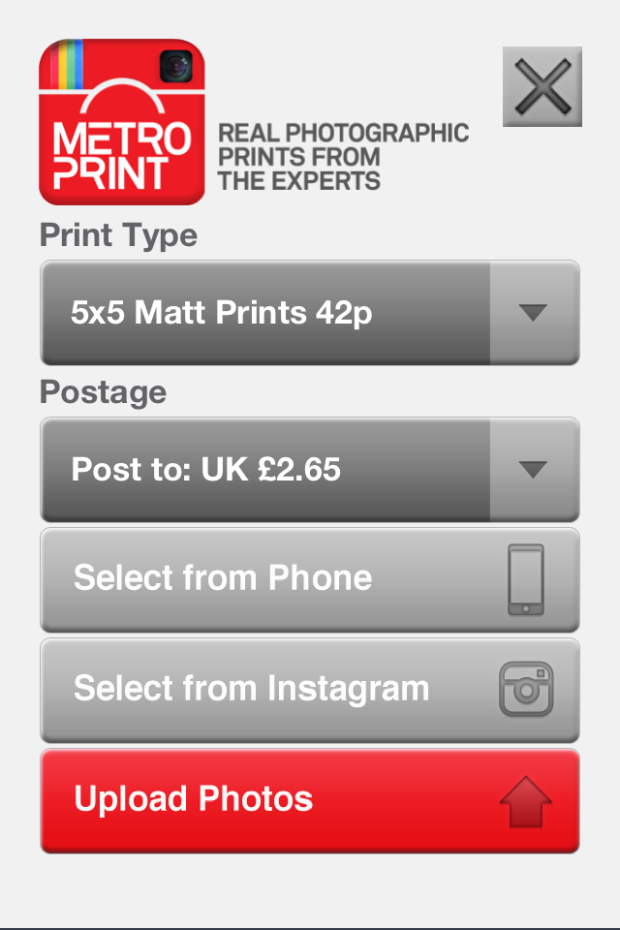

When Metroprint, a British-based photographic print service, launched its Instagram print service in November last year, I did rather haul it over the coals. For a start, when I first gave it a go, I couldn't order prints direct from my smartphone, but had used a desktop interface, and when this piece of bad design or flawed planning was finally rectified, the interface sucked. I was far from impressed. You can probably tell from  First impressions are indeed favourable. You hook up with Instagram from the app, select the images you'd like printed, opt for glossy or matt, upload the images, and pay via Paypal. Prints are 42p each. UK delivery is £2.65, European delivery costs £5, and anywhere else in the world is £5.50. You would, therefore, do well to bulk order as it's a little pricey for a single 5×5 print.

First impressions are indeed favourable. You hook up with Instagram from the app, select the images you'd like printed, opt for glossy or matt, upload the images, and pay via Paypal. Prints are 42p each. UK delivery is £2.65, European delivery costs £5, and anywhere else in the world is £5.50. You would, therefore, do well to bulk order as it's a little pricey for a single 5×5 print.