If you look at the top of your SLR camera, you’ll probably find a little round dial, which has a whole load of different settings on them. Some of them are automatic settings (like the green square), some of them are ‘creative automatic’ settings (like the little runner), and others are the modes that let you do the heavy lifting yourself (P, Tv, Av and M).

This little dial is called your mode wheel, and it’s your mortal enemy, the destroyer of creativity, and the root of all evil in the world including, but not limited to, wars, swine flu, and stepping in chewing gum with a new pair of shoes.

In this article, I’m going to show you the error of your ways (if you’ve been using it), or I’ll show you what each of the settings means, what it does, and how to recreate the effect by using the manual shooting modes instead.

Why do they upset you so much?

Good question. The creative automatic modes make me angry because they take important decisions out of your hands, but that’s not the worst of it: People who are using the creative automatic modes might, in the short term, be able to take photographs of a technical quality beyond what they would normally be able to, but if you resign yourself to letting your camera do the work and make the creative decisions for you, the problem is that you don’t understand the underlying theory behind what you are doing, and despite getting better results, you’re not becoming a better photographer.

Imagine, say, that you had an oven that would automatically detect what you put in the oven, then calculate how big it is, what you’re trying to do with it, and select the right temperature and time, before beeping at you when your Sunday roast / cake is finished or your socks are dry. (What? You don’t dry your socks in the oven? Hmm, just me, then.) Either way, the result would be perfect every time, but where’s the satisfaction in not knowing what your oven did to bake this cake? And more importantly, what if you want to take creative liberties – say, you might prefer your cookies a little bit American-style; gooey inside – or you might want to make them crispier, for example…

The purpose of this article, then, is to ensure that if you want gooey or crispy photographs, you know how much heat you need to turn on, for how long, and if your cookie tray needs to go in the top or the bottom of the oven.

Okay, enough of the dodgy similes already, let’s have it!

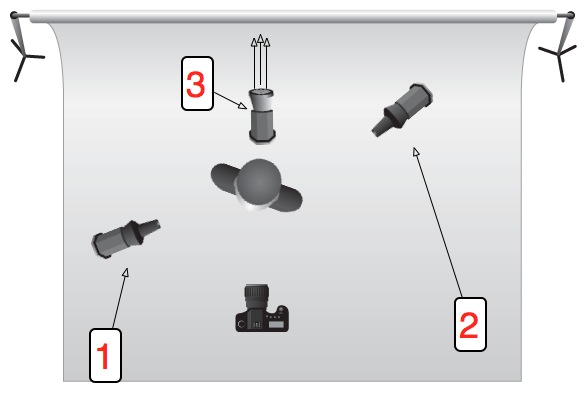

Right, in the picture above, starting from the top, going counter-clockwise, the modes are:

Suppress Flash

Why this is even a mode to itself I have no idea – depending on why you want to shoot without a flash, the easiest thing to do is to use Program mode (but also see Tv and Av, below), which means that the flash will only come on if you tell it to.

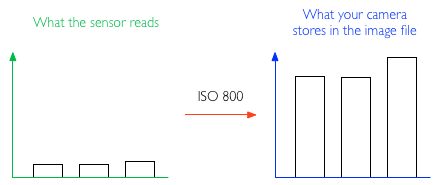

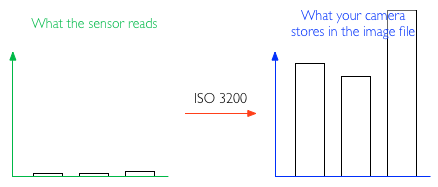

If you’re in a low-light situation, pick a higher ISO speed – this will create a bit more digital noise in your photo, but it means that you reduce the need for using a flash. If possible, select a bigger aperture so your shutter speed becomes lower.

Remember the general rule that you can hand-hold a camera at a shutter speed which is the same as the focal length of your lens: So if you’re shooting at 300mm, you should use 1/300 second shutter time or faster. If you’re using a sexy little 50mm prime lens, you can hand-hold at 1/50th of a second. Zooms are the same: if you’re using a 17-35mm zoom, you can hand-hold at about 1/10th of a second at full wide angle, and about 1/30th of a second at full zoom.

Of course, it’s possible to bend these rules, but if you adjust your ISO speed and shutter time to stick with them, you generally get a good, blur-free exposure without having to resort to using your flash gun.

Night-time portraiture

Night-time portraiture is the only of these settings which actually has any merit, in my opinion – not because it’s that difficult to do, but until someone has explained to you how you can get good night-time portraits, it can be a little bit counter-intuitive.

Imagine you’re in Paris with a loved one, and you want to take a photo of them, at night, with the Eiffel Tower in the background. You take a photo with a flash, and you can’t see the tower. You take a photo without a flash, and you can see the tower just fine, but your friend, who naturally is unable to stand still for more than a microsecond at the time, is all blurry and hazy. What to do?

Actually, Av is your friend: In Programme and Tv modes, the flash and shutter time will combine to try to expose your foreground correctly. In Aperture-priority, however, your camera will measure the light that is available to you, and then fire the flash to ‘fill in’ the foreground.

What, in effect, is happening, is that your camera is taking a ‘normal’ photo – exposed for the background – but then also uses the flash to expose the foreground correctly.

For further control (you might decide, for example, that the full 3-second exposure to get the ‘right’ exposure for the background isn’t necessary, and that the background looks OK after only a second, or fraction of a second), you can use full manual mode. On most D-SLR cameras and some external flashguns, you can also set the flash output manually, or adjusting it up or down. This differs from camera to camera (on the Canon, you’re looking for Flash Exposure Compensation, or F-EV), so check in your manual.

Top Tip: For creative effect, try to take a photo in AV mode, but move the camera or use the zoom while you’re taking the photo. Because of the flash your foreground will be static, but you get a hugely dramatic and awesome swirling, moving streaks effect because of the lights in the background.

Sports

Sports mode is a complete fraud: Use Tv mode, set to a fast shutter time (‘fast’ in this case depends on the sport you’re trying to capture. For snooker, fast isn’t very fast, and 1/60 of a second should do, but for horse racing, you need a much faster shutter time), and see what your camera comes up with.

If the pictures are too dark, it’s because your camera needs to use an aperture which is bigger than your lens can do (say, it’s using ƒ/5.6 but needs ƒ/2.8 to do the correct exposure). This is signified by a blinking aperture in your viewfinder, and can be solved by either using a lens with a larger maximum aperture, setting a higher ISO speed, or using a flash gun (although, say, darts players don’t really like it when flashes are going off in their face when they’re trying to throw A HUNNNNDRED AND EEEEEIGHTYYYYYYYY).

Macro

I know a couple of things about macro photography, and I genuinely can’t see a single good reason for that Macro mode being on a SLR camera. For a compact camera, sure: It puts the lens into a ‘focus close to the camera instead of in the far distance’ mode, which means that it’s not wasting its time trying to focus far away. On a SLR, if you’re savvy enough to have bought a macro lens, you probably will be fine with Programme mode, and if you haven’t got a macro lens, then you’re basically out of luck (unless you build your own, of course, but that’s a different article altogether).

To replicate this mode in the real world, use programme or Manual mode, use a macro lens, and snap away.

Landscape

Landscapes, glorious landscapes. Set your lens to manual focus, and turn it to the little ∞ (infinity) symbol. Note that it IS possible to focus past infinity – that’s because when you’re working with infrared photography, the light is refracted slightly differently, and you may actually need to focus past what is ‘infinity’ for daylight.

Anyway, your lens at infinity, set your mode dial to Av, and select a large-ish aperture. f/8 or f/11 is a good starting point.

Select as low an ISO mode you can get away with (bearing in mind the rule about hand-holding your camera, above, or just go ahead and use a tripod), and bob’s your uncle.

If you want to get advanced, and you need a very deep depth of field – say, for example – you want a person in the foreground, but you also want the background in focus – read up on ‘Hyperfocal distance’ and prepare to be amazed.

Portraiture

I can’t believe they created a separate thing for portraiture – do a search on Flickr for portraiture, and see what comes up. How can they possibly assume that one single mode fits all styles of portraiture?

Anywhoo – for getting good portraits, start with a reasonably long lens (130mm or so is perfect), stand back a little, use a large-ish aperture (ƒ/4 or so) to throw the background out of focus, and start from there.

Full automatic

This mode will select whether you use a flash or not, your ISO speed, your shutter speed and your aperture for you. It reduces your nice, expensive dSLR camera to nothing more than a big point-and-shoot. If I ever catch you (yes, you, I’m looking at you) with your camera set to the fully automatic mode, I’m afraid I’m going to have to ban you from visiting this site ever again.

Go on, live a little, flick your mode dial one notch, and enter the world of Program mode. The camera still does most of the thinking for you, but at least you are controlling it, rather than the other way around.

P – Program mode

Is one step up from automatic mode – and I confess to using it on occasion: The photographer selects everything except the aperture and shutter time, which the camera calculates for you. If it comes up with a combination of the two you don’t like, use your index finger wheel to change them – turn one way and you’ll see the aperture get smaller and the shutter speeds get faster – and vice-versa for turning it the other way, obviously. Use EV compensation to over- or under-expose your images a little, etc.

Program mode is great if you just want to get the right exposure, and you’re concentrating on just getting the photo, without worrying too much about depth of field etc. I know quite a few news photographers (!) who decided that manual mode was too finicky for them, and are shooting in programme mode most of the time. If it’s good enough for the national press, it’s good enough for me.

Tv – Shutter-speed priority AE mode

In Tv-mode, you dial in a shutter speed (say, 1/200 second), and the camera will attempt to get the ‘correct’ exposure by using the aperture to compensate for varying lighting situations.

… Interestingly, I very rarely use Tv mode, but that’s mostly because if I find myself in a situation where I want to actually control the shutter speed directly, I’m already shooting in fully manual.

One situation where it might be handy is if you’re shooting sports – say, rally racing – where you know you want a fast shutter speed, but the light can change quickly. The other situation I can think of is if you’re panning (i.e. a bicyclist comes flying past you, and you want to get them in focus while the background is out of focus), and you need a slightly slower shutter speed.

One thing to be aware of is that most lenses have a far more limited aperture range than your camera has a shutter time range. Think about it: your camera can do from several minute exposures to a fraction of a second, while your lens will only usefully span a much lower range. If you’re shooting in Tv, keep an eye on which apertures your camera is selecting for you, because if it’s getting too big, some of your photos might come out over-exposed

Av – Aperture priority AE mode

Av mode is the opposite of Tv mode, above: You select the aperture, and the camera calculates the right shutter time. Generally, I shoot either in Av or in fully manual, because for most of my photography, the depth of field (i.e. how much of the photo is in focus) is more important to me than whether the motion is frozen or not.

You get a deep depth of field by selecting a small aperture (ƒ/22, ƒ/32), or a shallow depth of field by selecting a big aperture (ƒ/1.8, ƒ/2.8).

When shooting in Av mode, still keep an eye on your shutter times – if they are very fast without you needing them to be, you may be able to use a slower ISO (switching from ISO 400 to ISO 200), which gives images with less noise. If they’re very slow, your photos might be coming out blurry, and you may want to ramp up the ISO or use a slightly larger aperture.

M – Manual

Go on. Try it for a week. You’ll love it. This is photography at its most control-freakishly delicious.

A-DEP: Automatic depth of field

...Is just plain weird. The idea is that you focus on the point that is furthest away, then on the point that is closest to you, and the camera will then focus and select the aperture you need for you. Basically, it’s using the Hyperfocal Distance (mentioned above, under landscapes), but in an automatic way which is actually more complicated to wrap your head around than just doing it yourself in the first place.

I think I can honestly say that I’ve never, ever used A-DEP before in my life, and that I don’t think I ever will. Give me manual exposure and a bit of guesswork any day of the week :-)

Go forth! Prosper!

So, in summary, what I would love for you to do is to reduce your photography to only four of the modes above: P, Tv, Av, M. if you’re feeling particularly hardcore, limit yourself to Av and M only.

And if you are a truly epic photographer with skillz beyond my wildest dreams, set your camera to M and pry the button off altogether. Chuck it away. You’ve graduated. Nothing’s gonna stop you now!

Originally published back in the mists of August 2012, but it bears repeating.

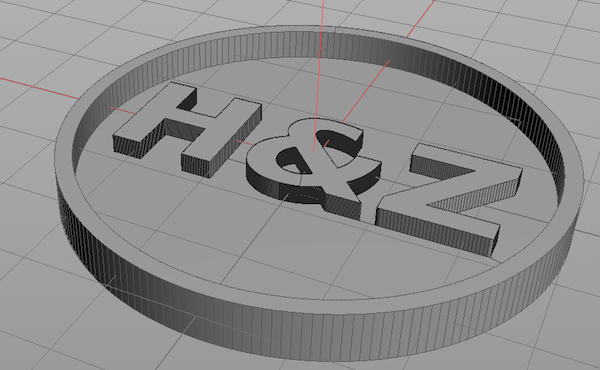

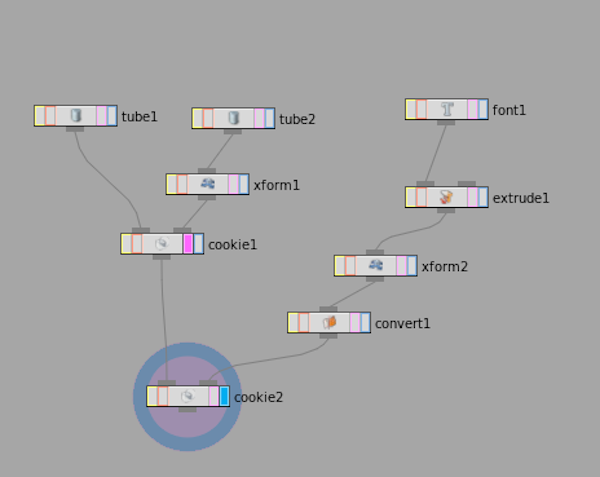

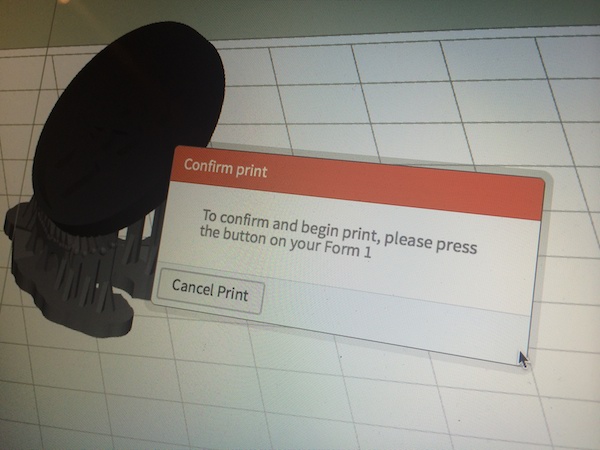

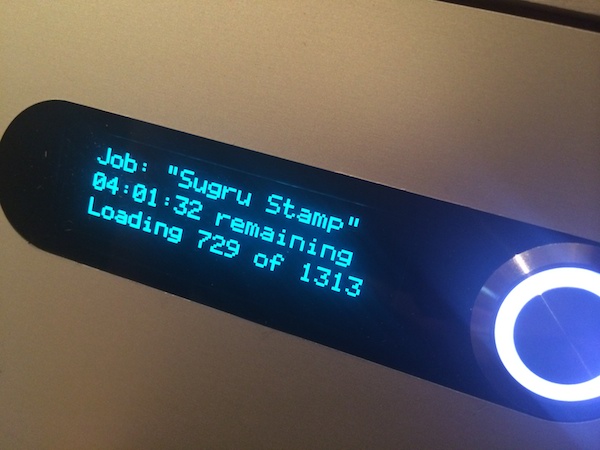

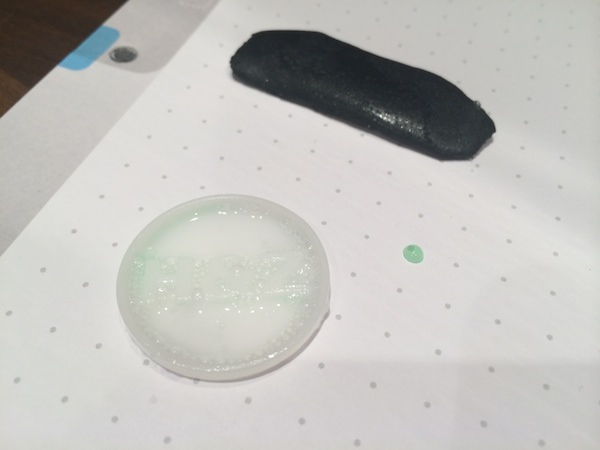

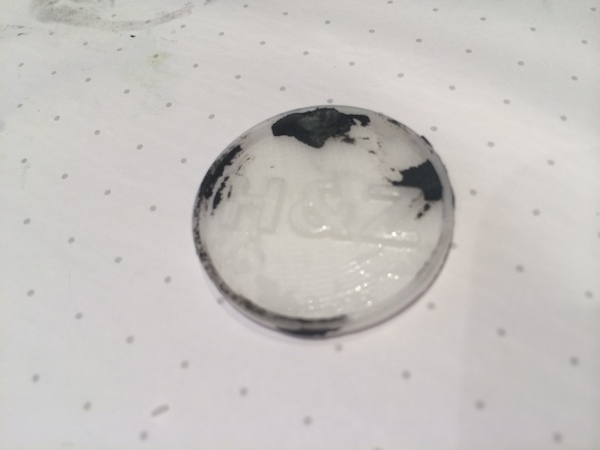

And the final stamp worked well! Hurrah!

And the final stamp worked well! Hurrah!

Every once and again, you need to clean your sensor properly; depends on how much you use your camera, but for me, it’s approximately every 2-3 months or so, a process which involves several of the products above. Here’s how to do it:

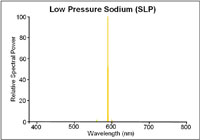

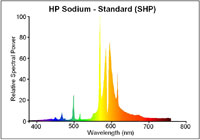

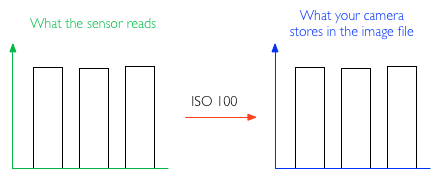

Every once and again, you need to clean your sensor properly; depends on how much you use your camera, but for me, it’s approximately every 2-3 months or so, a process which involves several of the products above. Here’s how to do it: The idea behind white balance is very simple: it's a way to correct all the colours in your image to take account of the light they were shot with. This is because not all light sources (bulbs, fluorescent strip lamps, conveniently nearby stars), produce light equally across the whole of the visible spectrum.

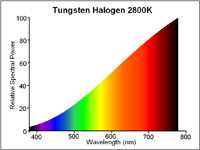

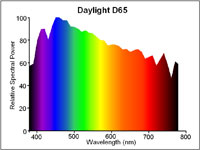

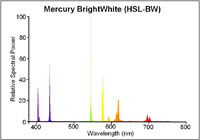

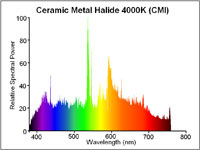

The idea behind white balance is very simple: it's a way to correct all the colours in your image to take account of the light they were shot with. This is because not all light sources (bulbs, fluorescent strip lamps, conveniently nearby stars), produce light equally across the whole of the visible spectrum.

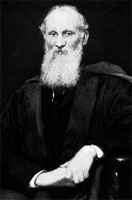

Colour temperature is measured in Kelvin (named after a rather clever physicist who was made Lord Kelvin in recognition of his work and, like all good Victorian scientists, had an excellent beard), which is pretty much the same as Celsius, but starts counting at absolute zero (-273 degrees C), rather than the freezing point of water. Its relationship to colour is actually the work of Max Planck who, being more recent German scientist, had a moustache, rather than a beard.

Colour temperature is measured in Kelvin (named after a rather clever physicist who was made Lord Kelvin in recognition of his work and, like all good Victorian scientists, had an excellent beard), which is pretty much the same as Celsius, but starts counting at absolute zero (-273 degrees C), rather than the freezing point of water. Its relationship to colour is actually the work of Max Planck who, being more recent German scientist, had a moustache, rather than a beard.

A spot of pinhole photography may help you break your photographer's block.

A spot of pinhole photography may help you break your photographer's block.