A while ago, I was talking with my good friend Randy Kruzan, who told me he had self-published a book – or, as he likes to put it – how he made the transition from “being a fool with a camera to being a fool with a book”.

There’s a lot of things that go into creating your own book (I should know, I’ve helped friends and clients self-publish things in the past, and I’ve been published with my own stuff) – but the interesting thing is that a lot of the things that take time aren’t the things you’d think…

I managed to talk Randy into writing a guest article for me here on Photocritic, explaining how his book came about, and what you should do if you want your photos to end up as a coffee-table book yourself.

The beginning

I was in a rut. No, that’s too cliche. I was between myself… yeah, that’s pretty accurate. My creative needs were being stifled by day-to-day work as a software engineer. On top of that, I was doing more of the same freelancing and, I have to tell you, there’s only so much left brain activity I can take. My right brain was screaming “There must be something more!” and there was. Is? Whatever.

Dave Browne, a friend of mine, former co-worker and fellow photographer, recently came back from an 18 month trip around the world. Upon his return we started having coffee once a week when schedules permitted. It would be melodramatic to say this changed my life, but it definitely put things in perspective. Call it a shove in the right direction.

Discussing photography with him is always enlightening, more for me than he, I think. He told me he was working on a book that he was going to publish himself. I had been playing with the very same idea for months but never found the time nor motivation, until he brought his book the next time we met.

It was gorgeous! The photos were taken on his trip with a Diana (that’s a plastic camera you pay real camera prices for through Lomo). The paper and finish were top notch, the design and layout were complimentary and it truly equalled traditionally published books.

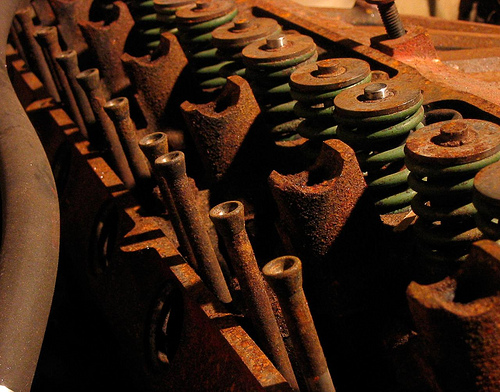

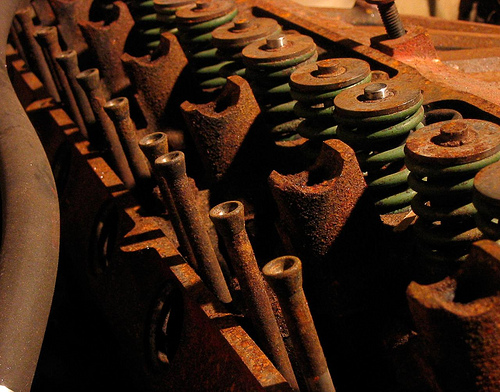

Cylinder Head by Randy Kruzan on Flickr

That was enough motivation, on the way home that night I decided to stop stalling. First I had to wrap up open freelance projects and stop taking more. Then I could get to work on my book. A couple of weeks later I was free(er).

After seeing Dave’s book, I realized mine could be better than I had been thinking about. Knowing I would never be good enough for myself (too critical), I asked him if he would help out with my book. He agreed and now I had an editor as well as someone to handle design and guide me through layout.

The middle

My theme was to be loss and abandonment, things left behind. I had several dozen photos fitting this theme taken over the last 4 years. Some black and white, some color and taken with two different cameras. Geographically they were split between Washington State and Illinois. Overall a nice smattering of styles, composition and colors.

I wanted a landscape oriented book with full bleed, so I cleared out any photos in portrait orientation. Next to go were any with focus or other technical problems. Eventually it filtered down to 32 photos. Now I could send them to Dave and get the editing and layout process underway. This is where it really pays to have someone you can collaborate with. Another eye, unbiased and critical, is invaluable.

We whittled those 32 photos down further. Some were just too bland, too flat. Others were great pictures but against the bulk of the remaining lot, didn’t fit anymore. Here I learned another lesson, to be flexible, to change direction if that’s where the photos are leading you.

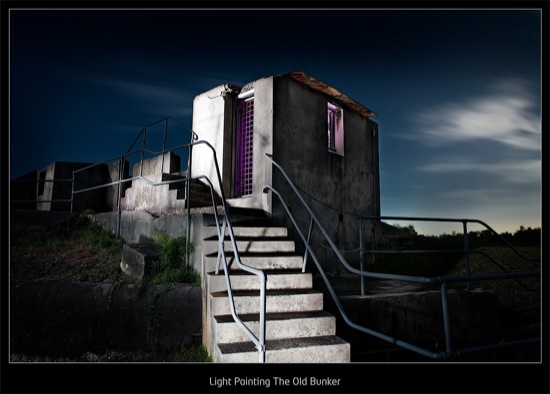

In my case, the theme of abandonment and loss had transformed into something a little different. The majority of photos I started out with were structures that were either abandoned or left to fall apart, but this didn’t stand out right away until we started cutting shots. The stack I was left with wasn’t saying loss any longer, it was saying something about persistence in the face of ruin. Yeah, these things were left alone or abandoned or simply neglected, but looking at them I could see that they were also surviving.

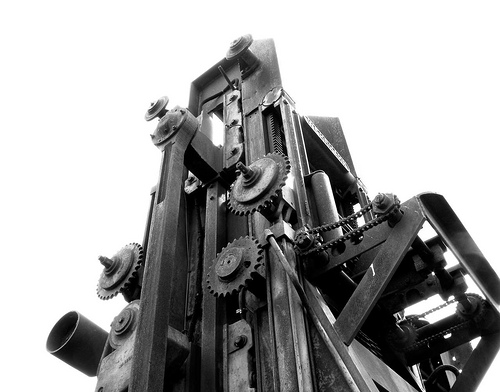

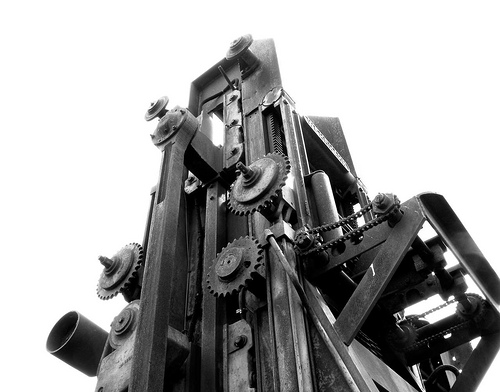

Mill Series #6 by Randy Kruzan on Flickr

By the end of a few rounds of this, I was down to less than 14 pictures. With a revised theme in mind and to add more bulk (you’ll see why that’s funny later), I set out to shoot some new photos, and reshoot some I had liked originally but rejected for technical reasons. While I did this, Dave began working on my layout and design. Out of another 50 or so new pics, 12 made my first cut. 7 were finally selected and sent to Dave, who approved. My count was now up to 21 and he had picked one for the cover. It wasn’t the one I had picked but after the title was added, I capitulated. It looked right. Dave is always right, ask him.

The end

All that was left was for me to write up the copy for my title and copyright page and an introduction, then it was up to him to tie it all together. We were almost done.

Almost. (Since you’ve already been reading this in a little voice in your head, go ahead and insert snickering laughter here)

In the last few weeks before we finished, I waffled on the title. Nothing I was coming up with fit, and every change meant a revision to part of the intro. If that wasn’t bad enough, I had second thoughts about some of the images. I wanted to pull some, add others. I realized I was still fighting for the old theme and kept trying to find ways to work that in somehow. That realization (and Dave telling me to leave it alone) was enough to get me over the last little hurdle and just give in to it. The final book is about things at the end of their useful lives, their defiance in the face of decomposition and neglect. I chose “finis” which is the temporal end. I subtitled it “Exploring the end”, revised my into copy and we were done.

He delivered, unintentionally, the final assets on my birthday and two days later my book was in manufacture. I used the same company he did, Viovio, since I had already seen the quality first hand. Nine days later I had the first print in my hands, and I have to say, I love it. With 21 images and the copy pages, it only comes to 12 paper pages! I laughed out loud when I opened the box and saw that. It didn’t occur to me during production that I was only going to have a 12 page book. It doesn’t matter. Dave did a great job, I am really happy with the pics and I think it’s a neat little book. Literally.

That’s my story about how a fool with a camera became a fool with a book.

How to self-publish

Now let’s talk about self publishing. What it is, why you should do it and what you stand to gain.

The road to publication

We’re photographers. As photographers we speak to the world through images we share. It’s natural to want to share those with as wide an audience as we can, and often dream of having our work recognized. The road to recognition for most of us is long, and unfortunately, sparsely populated. Oh, and, that road ends in a cul-de-sac, which is really just a fancy dead end, albeit one with a turn around. For those of us on this road, our turn around is self publishing.

Mill Series #5 by Randy Kruzan on Flickr

First, a little clarification. When I say self publish, I am not talking about the photo books you can have made at Shutterfly and similar services. For those, you pick a template, add pics and captions, pick your binding, and you’re done. Those are fine for keepsakes, and I’ve made them for birthdays and such, but they’re not the same caliber as an honest-to-goodness book.

What we’re talking about here is a product that when you’re done you can be proud of and looks professional.

So… What is self publishing?

Put simply, self publishing is paying to have your work published.

Traditionally, a publisher pays you to write or put together a book of your work. You get some portion of sales from the book and they handle the rest. Maybe it works out and you get another book deal and repeat the process.

When you publish your own work, you get to have all the fun. You pick the content. You come up with the design and layout, and edit it yourself. Promotions? Marketing? All you, baby! It can be a lot of work, and often is. Maybe it even SHOULD be! The sense of accomplishment and satisfaction of finally getting your first copy in hand after all of that work is worth it.

Will it make me famous?

Hmm. Stranger things have happened! Look at that guy Jared from the Subway commercials. At the very least, it can allow more people to enjoy your work and who knows what that can lead to.

Fine. Will it make me rich?

Probably not. I know that’s not what you want to hear, and I don’t want to crush any hopes you might have, it’s just not very likely. Like any other adventure, you’ll get out of it what you put in. You might make some money. For me, if I sell one copy more than I bought, I’ll be stoked. If I make enough money from self publishing books to buy a new prime or two, man, I’ll be on cloud nine.

Then why self publish?

Unless you already have a book deal, or are pursuing one and are extraordinarily lucky, incredibly persistent or some combination of those things, self publishing is the perfect way to share your work with the public NOW. Indeed, it may be the only way you’d ever get a book published, but that’s fine! You don’t need to be famous and your work doesn’t have to be well known to publish yourself. You might be a virtual nobody (case in point, myself), but a nobody with a book (dude, me again). If nothing else, it’s an exercise to see if you can do it.

Just remember… Always look on the bright side of life

I had this conversation with my friend and editor, Dave Browne, where I told him I didn’t have any illusions about doing this book. I don’t expect to become famous or land on some best seller’s list, but it would be nice to sell a few. He put it this way: “Buy two books. Keep one for yourself. If you sell two in a year, your demand will have outstripped supply!” Sure, it’s only two books, a minor detail, but your sales will have doubled in your first year.

Benefits of self-publishing

Do a little searching on the Internet for folks who self publish and you’ll find artists, authors, comic book artists and a whole host of others who have either had publishing contracts in the past or were pursuing them and were unhappy about how little control they had as new authors.

SP is a different world: yours.

You have complete creative control. What’s on the cover, how the book is laid out, what images and text go where, it’s all under your control.

You market or promote as much or as little as you want. Self publishing is perfect for photographers who run their own websites or blogs or have an online presence where they can advertise and promote their books.

You don’t have to hold inventory. Because self publishing is typically print on-demand, nobody actually holds your book in inventory.

You only pay manufacture on the copies you want to buy. If you want one copy of your book or twenty, you only pay manufacture on those copies. When someone else buys your book, they pay manufacture as part of the total cost.

You only pay manufacture on the copies you want to buy. If you want one copy of your book or twenty, you only pay manufacture on those copies. When someone else buys your book, they pay manufacture as part of the total cost.

You don’t have to handle sales and fulfillment. Unless you’re buying copies to hold onto and sell yourself, the printing company you’re using will handle taking money and shipping the books out to people who buy it.

You can make money on sales. Blurb is one company that allows you to set your own prices on your books at no extra charge. For companies that allow you to do this, there is a base rate (the price of manufacture) and you set your sale price, the difference between the two is yours.

You hold all the rights. The rights to your work are yours alone. Unless the company you’re dealing with has some clause to the contrary, you are the sole rights holder. If you find that’s not the case when shopping around, find someone else.

How to self publish

Or: ‘How I made self publishing made for you, without any guarantees that the same will work for you, but you could do a lot worse than starting here anyway’

Do you really want to do this? It might seem like a no-brainer, but it’s the first question you should ask yourself. There will be at least some monetary expense and of course the cost of your time. If you get a friend to help like I did, you should consider their time as well. Are they up for it? Start here. If you can’t commit, don’t start. Wait until you’re ready.

What’s it about? Do you want to tell a story with your photos like a photo essay? Or is it many stories? Is it just a portfolio? Is there a common theme it should have? Is it mixed photo and text, for example, like a guide book? You can always change this as the project progresses, but you should start out with a solid idea and build on it.

Know your choices, know the requirements – Shop around the service you’re going to use (or for that matter, shop around FOR services if you haven’t yet, see below). Do they have a product that matches your ideal book size and layout? What, if any, are the minimum page count requirements? Do you have images big enough for that size book? (I’ve included a link to a pixel to print size calculator at the end)

If you’re not using a service-provided tool (Blurb has an excellent book builder) then chances are high your final work will need to be a PDF, and any fonts you use will need to be embedded in the PDF. Check their publishing guidelines and know what you need to conform to in your final layout.

Will it bleed? – This is another point to consider before you actually start gathering up your prospects. If you’re going to do a full bleed book, where the image runs to the edges of the page without a border, then it’s probably best to choose photos that are all of the same orientation. No-bleed pages, or even multiple images per page, is less restrictive.

Gather, review, cull, repeat – Find all of the photos you think might work for your book. Digital is the way to go here, if your pics aren’t digitized already they’re going to have to be for printing, so really just do this now. If you have a favorite photo app with a workflow you’re used to, great- go with it. If not, the simplest thing to do is just copy (not move) all of the prospective images to a folder called “My Awesome Book”. For each round of review, make a new folder and only copy those images that make the cut into it. It’s draconian but when you have to dig up something from an earlier revision, you’ll know where it is.

Review your choices. Do they match what your book is about? Are there technical flaws you don’t like (and don’t want to or can’t fix)? Do some just not feel right? You’re never destroying pictures by excluding them, you should be as critical as you want here.

When you’re done reviewing and have made your choices for the next round, open them all up so you can view them in a batch. How does it look? Are you short of meeting the minimum page count? Add if you need to.

Repeat this process until you feel you’re at that point where they’re all good, then sleep on it and review again once more. If it’s still OK, then you have your final set.

Copy editing – Write all of your copy in a simple text editor. You’re not going to format your text until you’re in the layout stage, so simple text works well. It makes it easier to work with.

Regardless of how much text your book has, it’s a good idea to have it copy edited. Even if it’s simply asking your most grammatically advanced friend to review it, get a second set of eyes on it. Proof read. Spell check. Grammar check. Send me a check. Ahh, gotcha ;)

Cover yourself – You can’t judge a book by it’s cover… yeah, yeah, yeah, we do it anyway. Choose a legible font, no matter how cool the squiggly one you found looks. If your book is about puppies, don’t put a truck on it. Unless the puppies are stealing it. That would be awesome.

I prefer simple, but it’s your book. Choose a picture that represents the book.

Final touches – If the publishing service you went with doesn’t automatically build the copyright and title pages, spend a little time to see how those are laid out. I like to mirror the copy (font, placements and sizes) from the cover on the title page. Then the copy page, then the intro. Spend some time getting it right, good fit and finish is one of the things that sets a good self published book apart from the rest.

Layout and conversion – All of the SP services have different guides, sizes and requirements. This is why you should figure out ahead of time what the print guidelines are. Decent services will provide you templates to assist in the layout. In Design or similar publishing and layout software experience pays off here, my friends.

If you need to treat your copy in fancy ways, do it in this stage. Fonts, colors, leading, etc.

Most of the services I looked at all accept PDFs of at least the inner contents and a separate PDF for the cover. Fonts usually have to be embedded in the PDF. Viovio lets you do one PDF for the front cover and another for the back. If you’re not using tools (or using a SP service that doesn’t have tools) then PDF is the only way to go. Again, and I can’t stress this enough, follow their guidelines and requirements.

A simpler alternative – Layout can suck. It can be confusing and a pain. If it’s not your cup of tea, find a SP service that has a book builder tool. As of this writing, both Viovio and Blurb have such a tool available. These tools give you varying degrees of control over colors, styles, fonts, picture layouts and so on and so forth. If you’re going it alone and don’t have In Design skills, this may be your best bet. Don’t fear it. Embrace it.

And finally a word on rights – To nutshell it: If it’s not yours, don’t print it.

You must own or hold the rights to everything you publish in your book, or get written or other specified permission from the rights holder in order to use their materials. There are all kinds of details and legalities surrounding this, but that’s the high level and if you’re in doubt, don’t use it.

Not all publishers are equal

When you’re shopping for a publisher keep these things in mind: size, cost, quality and the ability sell your book.

When you’re shopping for a publisher keep these things in mind: size, cost, quality and the ability sell your book.

Product types – Do they have a book that matches your desired size and layout (portrait, landscape or square)? It’s also a good idea to look at the minimum page requirements. For some products you simply might not meet the final page count.

Costs and fees – How much are they charging you for your book size? Is it comparable to other publishers? What about retailing fees- are there any? Viovio, for example, will only let you set your own price and collect money on sales of your book if you pay for a $35/year membership. Other companies might not charge a fee, but may be limiting in some other factor like available sizes.

Print and paper quality – Before you settle on a publisher, be sure to read reviews from people who have used them. Solicit opinions from friends and colleagues. It’s also a good idea, if you can afford it, to print a sample book from a company you’re considering. It doesn’t have to be fancy, the idea is just to get it in your hands where you can judge the print and paper quality yourself.

Retailing – If your goal is to market your book and make money from sales, you should also look for the ability to retail your book through the publisher unless you’re planning on buying inventory to hold and sell yourself.

Popular doesn’t always mean great – Read reviews from other SP authors on the services you’re considering using. How do people feel about the final result? Was their system easy to use and navigate? Were there gotchas along the way?

To ISBN or not to ISBN, that is the question…

ISBN stands for International Standard Book Number. It’s a 10 or 13 digit code that uniquely identifies your book from every other book in the world. This is supposed to make cataloging easier or faster or some such thing.

Amazon’s CreateSpace is one of the SP services that will assign your book an ISBN if you don’t have one already, because your book will be sold through amazon.com.

Dead Lift by Randy Kruzan on Flickr (and also the cover of his book; ‘Finis’)

If you’re not planning on selling your SP book through a wholesaler, bookstore or other retailer, you probably don’t need an ISBN at this time. If you are contacted by a publisher who wants to publish and distribute your book, they will handle ISBN assignment at that point because part of the ISBN is the publisher code.

Get help, man – If you’re serious about self publishing your work and don’t have the skills (or the discipline) to manage the creation of your book, and don’t know someone who does, you’re in luck. Sort of. You just have to pay for it.

Some companies, like Blurb and BookSurge, offer professional help with editing, layout, design and/or final preflight. You can even buy a professional review for your book.

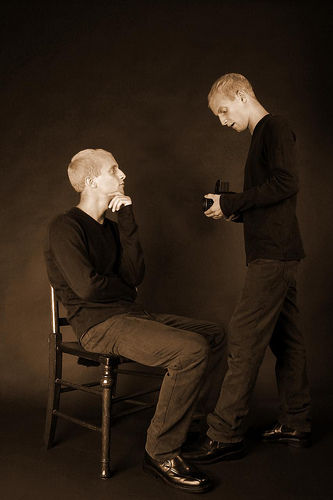

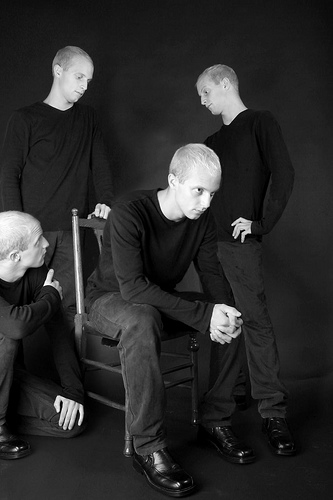

Making it better through collaboration – I honestly believe that my own book would not be half what it turned out to be if it weren’t for my friend who handled editing duties. Obviously if I felt he wasn’t up to the task I wouldn’t have asked him, so keep that in mind if you approach your friends or colleagues.

Once you’ve acquired help, figure out who is doing what. Better yet, you should have an idea of what you need help with before you go asking. If they’re only agreeing to do cover design, for example, you might not want to push book layout on them as well. If they’ve agreed to copy edit, let them. Don’t assign work and take it away.

Keep it fun, and be open to criticism and feedback. It is your book, but if you’re asking advice, at least hear it with an open mind.

Getting them to commit to your project is just as important as you making sure you respect their time and effort. You both have to be on the same page. (Booooooo, bad pun, I know)

Closing – The subject of self publishing could really be turned into a book itself, and I hope that I’ve been helpful here in this space sharing my own SP story and giving some information and advice.

Thanks very much to Haje for the invitation to guest write on Photocritic.org, it was a much needed break from the 140 character world of twitter.

About the author

Randy Kruzan is a photographer and author well disguised as a software engineer. He lives near Seabeck, Washington with his awesome family. Tweet him up @randykruzan on twitter or on the Internet at randykruzan.com

Randy Kruzan’s book can be purchased from Viovio

More resources

Publishing and print on-demand services

Blurb – blurb.com

Viovio – viovio.com

Other resources

Amazon’s self publish and print on demand – createspace.com

Amazon’s assisted publishing – booksurge.com

Pixel to print size calculator at ScanTips.com – scantips.com/calc.html

Do you enjoy a smattering of random photography links? Well, squire, I welcome thee to join me on Twitter -

© Kamps Consulting Ltd. This article is licenced for use on Pixiq only. Please do not reproduce wholly or in part without a license. More info.

Sure, there are always groups of people who will perennially have an insatiable hunger for more processor cores, more memory, and more storage space; serious gamers, video editors, and scientists spring to mind – but even for the power-users (I do count myself as one), we’re starting to hit a plateau where it’s perfectly okay to own a 3-year-old computer. Which just messes with my brain; when I first started getting into computers, the second you bought one, it was out of date. I remember the first time I plonked down a serious amount of money on a new computer (before then, I’d always had hand-me-downs or I’d bought second-hand computers) – it was a Dell, which had a Pentium III, 600 Mhz. I’m telling you, it was the cream-of-the-crop, one of the fastest computers you could buy. It had a whopping 1GB of memory, too, which was insanely expensive, and made it incredibly fast indeed. Six months later, I found myself upgrading several of its components, and six months after that, again. And again. And again.

Sure, there are always groups of people who will perennially have an insatiable hunger for more processor cores, more memory, and more storage space; serious gamers, video editors, and scientists spring to mind – but even for the power-users (I do count myself as one), we’re starting to hit a plateau where it’s perfectly okay to own a 3-year-old computer. Which just messes with my brain; when I first started getting into computers, the second you bought one, it was out of date. I remember the first time I plonked down a serious amount of money on a new computer (before then, I’d always had hand-me-downs or I’d bought second-hand computers) – it was a Dell, which had a Pentium III, 600 Mhz. I’m telling you, it was the cream-of-the-crop, one of the fastest computers you could buy. It had a whopping 1GB of memory, too, which was insanely expensive, and made it incredibly fast indeed. Six months later, I found myself upgrading several of its components, and six months after that, again. And again. And again.

I selected a plain white wall with a wooden door as the background for my pictures, no direct sunlight but no artificial light either, and set-up my Canon EOS 20D on a tripod. I made the necessary adjustments in terms of sensibility and focus, selected the B&W mode, and used the self-timer to take the pictures. Between each shot I practiced in front of a full length mirror… I wanted to be able to share these pictures with my children when they grow up, so I was determined to be as beautiful as possible (of course!), and if sensuality was permitted, I did not want these pictures to turn out erotic.

I selected a plain white wall with a wooden door as the background for my pictures, no direct sunlight but no artificial light either, and set-up my Canon EOS 20D on a tripod. I made the necessary adjustments in terms of sensibility and focus, selected the B&W mode, and used the self-timer to take the pictures. Between each shot I practiced in front of a full length mirror… I wanted to be able to share these pictures with my children when they grow up, so I was determined to be as beautiful as possible (of course!), and if sensuality was permitted, I did not want these pictures to turn out erotic.

Many people do not wish to be photographed, for many different reasons. Native peoples, such as some Native Americans in the US, might refuse being photographed because they believe a mirror does not reflect reality, but a persons’ soul. A picture, taken by a device that relies heavily on mirrors, may therefore capture and enslave the soul. Sometimes, this restriction only counts for infants and children, as their souls are fragile, and can more easily leave the body.

Many people do not wish to be photographed, for many different reasons. Native peoples, such as some Native Americans in the US, might refuse being photographed because they believe a mirror does not reflect reality, but a persons’ soul. A picture, taken by a device that relies heavily on mirrors, may therefore capture and enslave the soul. Sometimes, this restriction only counts for infants and children, as their souls are fragile, and can more easily leave the body. In some countries, such as China, taking someone’s picture without their consent is simply extremely rude. Others might feel they are not photogenic, and do not want their face to be splashed all over Flickr. And you need to be wary that some locations (places of worship, official buildings and structures, museums and military bases) may prohibit photography for security reasons.

In some countries, such as China, taking someone’s picture without their consent is simply extremely rude. Others might feel they are not photogenic, and do not want their face to be splashed all over Flickr. And you need to be wary that some locations (places of worship, official buildings and structures, museums and military bases) may prohibit photography for security reasons. But, in general, rule number one is, get permission. It is essential that your behaviour and attitude is not one of right, but one of friendly coexistence. When you smile and nod while pointing at your camera, it is pretty clear what you want. This might sometimes mean that your photo will not be as spontaneous as you might wish, but at least you will not end up in sticky situations where the subject feels their personal space, or religion is violated. Especially on the topic of photographing children, you need to be very cautious, make sure to ask the parents or guardians for permission, no matter where in the world you are.

But, in general, rule number one is, get permission. It is essential that your behaviour and attitude is not one of right, but one of friendly coexistence. When you smile and nod while pointing at your camera, it is pretty clear what you want. This might sometimes mean that your photo will not be as spontaneous as you might wish, but at least you will not end up in sticky situations where the subject feels their personal space, or religion is violated. Especially on the topic of photographing children, you need to be very cautious, make sure to ask the parents or guardians for permission, no matter where in the world you are. Rule number three is that if someone asks you to stop taking photos, either verbally, by turning away, by looking uncomfortable, or by running for cover, as happened to me in Vietnam, stop. No matter the reason why someone might want you to stop, it is important that you keep in mind what Darren Rowse

Rule number three is that if someone asks you to stop taking photos, either verbally, by turning away, by looking uncomfortable, or by running for cover, as happened to me in Vietnam, stop. No matter the reason why someone might want you to stop, it is important that you keep in mind what Darren Rowse

Are you looking for the perfect Christmas gift for that special photographer in your life? If so, you’ve come to the right place. I know from personal experience that present shopping for photography-obsessed people can be tough.

Are you looking for the perfect Christmas gift for that special photographer in your life? If so, you’ve come to the right place. I know from personal experience that present shopping for photography-obsessed people can be tough. Looking for an inexpensive photography related gift? I won’t lie; sometimes it can be tough to find a good photography gift in this price range, especially with everyone switching to digital.

Looking for an inexpensive photography related gift? I won’t lie; sometimes it can be tough to find a good photography gift in this price range, especially with everyone switching to digital. In this range, I’d recommend the

In this range, I’d recommend the  Once you get into this price range its possible to start looking at some decent tripods and lenses. However, before you go out and buy a tripod for your photographer friend, be warned that both tripods and lenses can be very personal things for some photographers.

Once you get into this price range its possible to start looking at some decent tripods and lenses. However, before you go out and buy a tripod for your photographer friend, be warned that both tripods and lenses can be very personal things for some photographers. Alright, now we’re talkin’. In this price range, you can really find some quality lenses.

Alright, now we’re talkin’. In this price range, you can really find some quality lenses. Bestower of Christmas joy…

Bestower of Christmas joy… Now that you’re ready to start pulling out the big bucks, you’ve got a very important choice to make.

Now that you’re ready to start pulling out the big bucks, you’ve got a very important choice to make. If you are really willing to go all out this Christmas (and I mean really all out), then consider buying a medium format digital camera from Hasselblad. We’re talking about the high end of the high end here.

If you are really willing to go all out this Christmas (and I mean really all out), then consider buying a medium format digital camera from Hasselblad. We’re talking about the high end of the high end here.

The human senses have an absolutely incredible dynamic range – think about it: when you’re inside a concert venue at a rock gig, you can hear every note and enjoy every instrument.

The human senses have an absolutely incredible dynamic range – think about it: when you’re inside a concert venue at a rock gig, you can hear every note and enjoy every instrument. A couple of years ago, I believe when I got the then-brand-new-on-the-market Canon EOS 20D, I decided to switch to RAW. I spotted that the quality was better than with JPEG, and I stuck with it. Mostly, I did it because I could never quite get the

A couple of years ago, I believe when I got the then-brand-new-on-the-market Canon EOS 20D, I decided to switch to RAW. I spotted that the quality was better than with JPEG, and I stuck with it. Mostly, I did it because I could never quite get the