Part 1 of 2. At the bottom of this article, there's a link to an article detailing how you can defend yourself against copyright infringements. If you're looking for practical advice, that might be the best call.

Hi. I’m Haje. I’m a writer and a photographer. I am probably not the best writer in the world, and I’m certainly not the best photographer in the world. And yet, I make my living as a writer, which means that I’m good enough that quite a few editors and publishers out there think that it is worth paying me money to write.

A lot of my writing goes into magazines and books, but I also do a lot of writing for free, especially here on Pixiq. Why? Well, I have a lot of words in me which are pining to escape, and I rather like having an outlet where I am my own editor: I decide what gets published, what gets said etc. And I take a perverse pleasure from looking at the statistics. Put together, my top 3 most-read articles (smoke photography, macro photography and top 50 websites) have been read more than a million times. That’s a lot of people reading what I have to say about photography.

Of course, whilst the content on Pixiq is ‘free as in beer’ for my end users, I do enjoy some benefits from running a moderately successful blog. My books are selling quite well, which is at least in part because people become aware of me and my blog. I make enough money via Google AdSense to pay for my hosting costs and to buy a bottle of beer every few weeks… And, well, I enjoy the fact that people are reading and commenting on my stuff: Without my blog, I wouldn’t have nearly as big an audience, and I enjoy the feeling of being ‘on the pulse’ of the photography community across the internet.

When people steal my content on the internet, I get very angry. At some point, I decided to fight back. This post explains why and how.

You’re not just going to rant, aren’t you?

Well yeah, pretty much. Sorry. But I’ve learned a lot from fighting copyright theft throughout the years, so if you want the actually useful advice, check out part 2 of this article, that's where I'm actually trying to help you.

What is copyright?

I know that there are a lot of people who are fiercely against copyright – who feel that music should be freely available, that all software should be downloadable, and that people protecting their copyright are devils. If you are among those people, you’re probably not going to like this post much, but stick with me – or at least read ‘How copyright infringement harms me’, below.

Copyright is really quite simple: Whenever you create something, copyright is also created. This happens completely automatically: you don’t have to register your copyright, you don’t have to stick the silly little © symbol on your work, and you don’t have to stand next to the master copy of your copyrighted work with a katana and a grim look on your face to make people understand that something is copyrighted. In fact, it’s usually more correct to assume that something is copyrighted.

Whilst most of the words I’m typing now are in the dictionary (unless I mispell them, in which case they wouldn’t be in the dictionary, but that’s a different point altogether), the order I choose to put them in is my ‘creation’. This creation is something that belongs to me: I have the right to decide who gets to use these words, for what, and under which conditions. I can decide that everyone who reads it would have to give me a cookie or a copy of Wired magazine, for example. Nobody would, of course, but that’s not the point: I get to decide.

I am creating something that is my property, and if someone decides to copy this and upload it elsewhere, my property is being ‘stolen’.

There are ways of losing your copyright, but (in the UK, at least) all of them involve signing a piece of paper. Your work contract, if you are a journalist, might assign the work you produce to the copyright. Wiley Publishing published my first book, but I have a contract which stipulates what they are allowed and not allowed to do with the words I have written, and how much money they owe me if someone decides to make ‘Macro Photography: The Movie’. (No, seriously. Movie rights is part of my contract.)

If my good friend Maxwell Lander (link not always safe for work) asked me nicely if he could use one of my articles on his site, I can grant him permission (in effect, I would be extending a licence to his site), or deny his request. The copyright would still be mine, so if someone found my article on his site, and wanted to re-use it elsewhere, they would have to come back to the copyright holder (myself) to ask for permission before re-using it.

Copyright vs. other types of theft

The problem with copyright ‘theft’ is that it isn’t analogous to other types of thieving. If you were to steal my laptop, it is easy to understand why I would be upset: I don’t have a laptop anymore, and you have my laptop: You have clearly deprived me of something that used to be ‘mine’. Short of going all Proudhonesque, I think most people can agree that it’s ‘wrong’ to take something which belongs to somebody else. Copyright is often more difficult to understand for people.

If I have bought a copy of Mark Helprin’s Refiners Fire, and I’ve finished reading it, you might ask me to borrow it. I’ll lend it to you, of course, because I think everybody should read Refiners Fire. As far as Helprin is concerned, nothing bad has happened: I have bought the copy of the book, and I’m allowed to do whatever I want with it. I can set it on fire. I can read it every week for the next 15 years. I can give it away via BookMooch, sell it on eBay, or lend it to my friends, if I want. No problem here.

If I have bought a copy of The Decemberists’ Castaways and Cutaways, I could do much of the same: I can lend it to my housemate, sell it to a friend, or throw it away when I’m tired of it. I can even transfer it to another medium: At the moment, I’m listening to that very album on my laptop, where it lives in glorious, high-quality M4A format. The ‘loophole’ here is that I still have the CD: I can see it from here. If I were to sell the CD, however, I’d be in trouble: The CD is the ‘licence’ for me to listen to the music.

In both the above situations, I have made a physical purchase. If I were to photocopy the book for a friend (never mind that it would probably be more expensive to copy the book than to just order another copy from Amazon or something), I’ve made a transgression. If I were to give a copy of the CD, I’m in the wrong. It’s pretty easy to understand, too: When I make a copy of a CD or a book, I’m depriving the artist/writer of royalties. As a (struggling) writer myself, I can see how that is upsetting.

Where it gets more complicated, is how I routinely give away my content for free (you’re reading my blog now, aren’t you? Did you pay? Of course not, and I don’t expect you to), but still be upset when someone steals it? You can’t steal something that’s free, can you?

How copyright infringement harms me

I'm the guy on the left. That is my angry face. I don't make my angry face too often, but people nicking my content might see it...

There are many ways you could be in infringement of my copyrighted content: Turn it into a book and sell it under your own name, and chances of me finding out are very slim. Print out copies of an article for your photography club, and there’s no way I would ever know. And still, I wager that most people would agree that the former is worse than the latter. Why? Because now someone is making money off the back of my hard work. If it turns out that what I am writing here is worth money, then I should be the one benefiting from it, right?

Most of the time, infringements happen when someone takes one of my articles and posts it to their own website, either manually (by copying and pasting the text from my site) or automatically (by taking the RSS feed and showing it on their site in its entirety). This means that my articles show up on another site, which harms me in several different ways:

SEO – I have spent a fair bit of time (and some money) ensuring that my sites are designed and developed to best practice Search engine optimisation (SEO) rules, which, in turn means that I rank better in the search engines. There’s no big secret to how to do this – I wrote a separate article about making google love your photography site, in fact.

One of the things that influences your rankings is content duplication. In theory, when people take my content and put it elsewhere, it dilutes my chances of people finding my site. This means that I get less traffic to my site, which in turn reduces the benefits I get from posting my articles for free. The other sites probably don’t promote my book, they don’t give me their advertising money, and they don’t make me feel like a super-hero.

Cold hard cash – I don’t make a lot of money off this site. Most months, I only barely manage to pay for my hosting costs for my server, domain, etc.

Control and reputation – If it turns out that I write something that is incorrect, I am relatively likely to correct it. Imagine if I wrote something that was completely wrong, and might actually damage your camera – if that were to happen, I would immediately post a retraction, a correction, and make people aware of it over Twitter etc.

However, if someone has copied the article to elsewhere, those articles would remain out there – some times, with my name attached… and if someone follows that advice and breaks their camera, what would happen then? I would feel terrible, which is bad enough, but it also puts my reputation at risk.

Cross-marketing – There’s a picture of my books in the sidebar of my site. Every time you see my site, you see a picture of my book. You may not buy it. You may never even notice it. But the next time you’re in a book shop, you might spot it. You might remember it. You might buy it. And for every book I sell, I’m likely to be contacted by a publisher to be able to write another book.

Principle – Many of the people who steal my content don’t do it out of malice. Often, they just get really excited by something I have written, and want all their friends to see it, too. It’s flattering, in fact, but in the process they break the law and upset me. Often, a quick e-mail is enough to help them realise why it upsets me, and the content vanishes quickly. I even had someone send me a lovely box of chocolates and a post-card by way of apology once.

There is a second group of people who nick my content though: The ones who do it to make money. People who systematically steal other people’s content in order to try to get a little bit of traffic from search engines, which they then monetise in one way or another. Affiliate sites selling photo equipment, for example, or sites that simply want to run advertising on my content. Or even unscrupulous photographers who want extra traffic to their site to try and sell their photographic services.

This hurts me in two ways: not only am I competing against my own content in the search engines, but if someone clicks on their adverts instead of mine, this hurts me in the wallet, too: The $0.0001 per click that I would have gotten goes to someone who willfully breaks the law. It’s not about the money (I’m not poor enough to start a fight every time someone steals a fraction of a penny out of my pocket), but about the audacity of doing that, and thinking you can get away with it.

But you have an RSS feed! Isn’t that just begging for it?

Actually, never mind the previous picture. This is my real angry face.

For the longest time, I was running a truncated RSS feed: Basically, you see the first 100 words or so, and nothing else, you’d have to click on the link to come read the full article. Then, a while ago, I had a few people e-mailing me, asking me very nicely if I couldn’t please change it to the full RSS feed, because they preferred reading my site in the feed.

I looked into it, and decided to go for it, for several reasons: I could add advertising to the RSS feed, so in theory I wouldn’t be out of pocket (in addition, fewer readers on the site means, in theory, less bandwidth costs – but that’s moot: I’d rather pay the costs and have more people on my site). In addition, I’m a bit of a geek, and I love Google Reader – I want to be able to catch up with things that way, without incessantly loading up more pages.

A few people immediately started using my RSS feed, piping them into other sites, and essentially creating a clone of my site. They mistakenly thought ‘Hey! He’s got an RSS feed, so it’s okay to syndicate his content’. As we discussed above, in ‘what is copyright’, that’s not the case at all: I might leave a copy of my book on a photo copier machine, but that doesn’t mean I’ve agreed that people can copy it at will.

Think about the examples from the beginning of this article: Making a copy of a 500-page book is a lot of effort and costs a fair whack of money, so people are unlikely to do it. Making a copy of a CD is a lot easier. Scraping my site is even easier, and using my RSS feed to nick my content is easier still: but just because it is easy, doesn’t mean it’s legal.

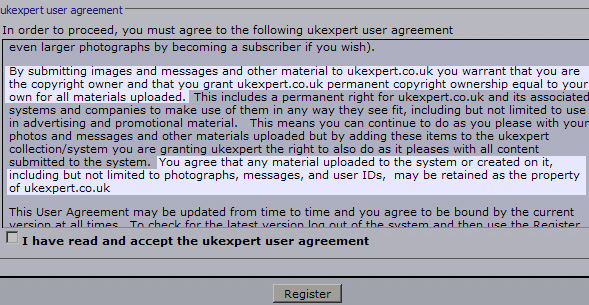

My RSS feed has a copyright notice in it which currently reads:

Please note that all Photocritic content is © 2001-2010 Kamps Consulting Ltd. This RSS feed is provided for personal, non-commercial use only.

If you are not reading this material in your news aggregator or RSS reader, the site you are looking at is guilty of copyright infringement. If you spot this anywhere, please contact legal@kamps.org so we can take legal action immediately.

As we said: As the copyright owner, I’m fully within my right to create all sorts of outlandish conditions of use of my own content. In this case, the only conditions are ‘personal use’ (so, don’t distribute it on- or off-line) and ‘non-commercial’, (so, don’t try to make money off my content).

From my perspective, I’m not all that fussed if people e-mail each other copies of my articles: As long as I am not competing against myself in Google et al, it’s not a fight I’m likely to find worth fighting. The great thing about most RSS readers is that they are ‘closed communities’ – Unless you are logged into Google Reader, you can’t see any feeds. This means that search engines don’t index RSS readers – as such, they are not in competition against me for search engine traffic. If someone re-publishes my content on their site, that’s a different matter altogether.

Disclaimer

I have rudimentary legal training in UK media law, but my training is several years old, and you’d be insane to take legal advice from some random bloke off the internet anyway. Nothing in this post is meant as actual legal advice – talk to your solicitor, that’s what they are there for!

Further Reading

Further Reading

This is part of a 4-story series:

- What is copyright, and how do infringements harm you?

- Protecting your copyright in a Digital World

- Just because it's in my RSS feed, doesn't mean you get to steal it

- Ignorance is no excuse

In addition, you might enjoy Police Fail: Copyright, what is that? and Even Schools Don't Care About Copyright...

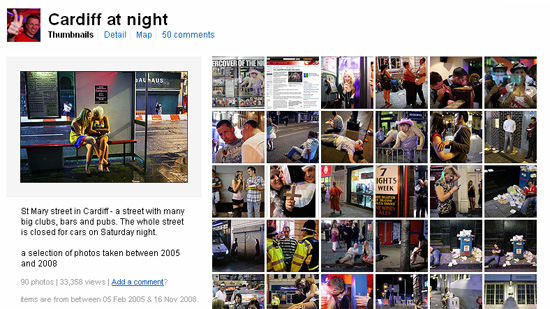

Many people do not wish to be photographed, for many different reasons. Native peoples, such as some Native Americans in the US, might refuse being photographed because they believe a mirror does not reflect reality, but a persons’ soul. A picture, taken by a device that relies heavily on mirrors, may therefore capture and enslave the soul. Sometimes, this restriction only counts for infants and children, as their souls are fragile, and can more easily leave the body.

Many people do not wish to be photographed, for many different reasons. Native peoples, such as some Native Americans in the US, might refuse being photographed because they believe a mirror does not reflect reality, but a persons’ soul. A picture, taken by a device that relies heavily on mirrors, may therefore capture and enslave the soul. Sometimes, this restriction only counts for infants and children, as their souls are fragile, and can more easily leave the body. In some countries, such as China, taking someone’s picture without their consent is simply extremely rude. Others might feel they are not photogenic, and do not want their face to be splashed all over Flickr. And you need to be wary that some locations (places of worship, official buildings and structures, museums and military bases) may prohibit photography for security reasons.

In some countries, such as China, taking someone’s picture without their consent is simply extremely rude. Others might feel they are not photogenic, and do not want their face to be splashed all over Flickr. And you need to be wary that some locations (places of worship, official buildings and structures, museums and military bases) may prohibit photography for security reasons. But, in general, rule number one is, get permission. It is essential that your behaviour and attitude is not one of right, but one of friendly coexistence. When you smile and nod while pointing at your camera, it is pretty clear what you want. This might sometimes mean that your photo will not be as spontaneous as you might wish, but at least you will not end up in sticky situations where the subject feels their personal space, or religion is violated. Especially on the topic of photographing children, you need to be very cautious, make sure to ask the parents or guardians for permission, no matter where in the world you are.

But, in general, rule number one is, get permission. It is essential that your behaviour and attitude is not one of right, but one of friendly coexistence. When you smile and nod while pointing at your camera, it is pretty clear what you want. This might sometimes mean that your photo will not be as spontaneous as you might wish, but at least you will not end up in sticky situations where the subject feels their personal space, or religion is violated. Especially on the topic of photographing children, you need to be very cautious, make sure to ask the parents or guardians for permission, no matter where in the world you are. Rule number three is that if someone asks you to stop taking photos, either verbally, by turning away, by looking uncomfortable, or by running for cover, as happened to me in Vietnam, stop. No matter the reason why someone might want you to stop, it is important that you keep in mind what Darren Rowse

Rule number three is that if someone asks you to stop taking photos, either verbally, by turning away, by looking uncomfortable, or by running for cover, as happened to me in Vietnam, stop. No matter the reason why someone might want you to stop, it is important that you keep in mind what Darren Rowse

I’ve stumbled across Jason’s site,

I’ve stumbled across Jason’s site,  “Basically”, he says, “I launched it as a site to try and sell my own pictures as canvas and poster prints 5 months ago. Then I realised that there are so many really good photographers out there, completely unknown, yet they have no idea about the internet or how to create a website to sell their work and earn some extra cash.”

“Basically”, he says, “I launched it as a site to try and sell my own pictures as canvas and poster prints 5 months ago. Then I realised that there are so many really good photographers out there, completely unknown, yet they have no idea about the internet or how to create a website to sell their work and earn some extra cash.”