We might think that media stars have very carefully controlled images today, what with their agents, their publicists, and the cavalcade of lawyers that protect their interests at every given turn, and in Kate Moss’ case, Oxfordshire Police who cheerfully closed roads through two villages for her recent wedding. But in reality, the paparazzi and every Tom, Dick, and Harry, and Emma, Jo, and Sarah having cameras on their mobile phones makes them quite accessible. Definitely not so for Hollywood stars from the 1920s to the 1960s; their images really were administered with rods of iron by their studios.

Studios wanted people to think that their stars were inaccessible and imbue them with air of mystique, so the only photos available of them were the photos released by the studio, taken by a small pool of photographers who worked closely with them. Photographers included Davis Boulton, Ruth Harriet Louise – the only woman to run a studio photo gallery – and Clarence Sinclair Bull. It wasn’t usual for one photographer to build up a relationship with a star, either.

Interestingly, these photos were usually marked ‘copyright free’ so that they could reach as many people as possible, and draw them into cinemas. These stars’ images would be everywhere, but it would be precisely the images that the studio wanted to project of them, and who knew about the photographers?

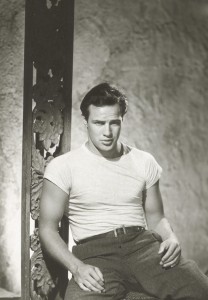

The NPG’s new exhibition Glamour of the Gods brings together 70 vintage prints, some iconic and some previously unseen, taken by nearly 40 different photographers, of film stars from 1920 to 1960. All of the images have been drawn from the John Kobal Foundation.

Kobal collated an extensive collection of these images, at first because of his interest in the films and their stars, but later because of the relationship that he built with the photographers behind them and his desire to see their work preserved and acknowledged. What with the images being ‘copyright free’, it was all too easy for the photographer to be forgotten.

If you get the chance, do wander along to the NPG and marvel at the product of a now-dead studio system. Enjoy the publicity shots that needed to encapsulate a film in one image; the perfect presentation of these gods of the silver screen, and the work of photographers who might otherwise have gone unrecognised.

Glamour of the Gods runs from 7 July to 23 October 2011 at the National Portrait Gallery, St Martin’s Place, London, WC2H 0HE.

(Featured image: Clark Gable and Joan Crawford for Dancing Lady, 1933 by George Hurrell © John Kobal Foundation, 2011.)